Devolution is the transfer or delegation of power to a lower level, especially by central government to a local or regional administration. This is different to a federal state where power is shared between states and the central (federal) government. In such a model, provinces have a constitutional right to disobey the central government, and execute their own policies and laws in certain (non-federal) areas. Therefore, in origin the caliphate is a unitary state with devolution and not a federal state even though the differences between the two are small. In the case of America’s federal model, it’s almost identical administratively to how a future caliphate would look i.e. a United States of Islam (USI).

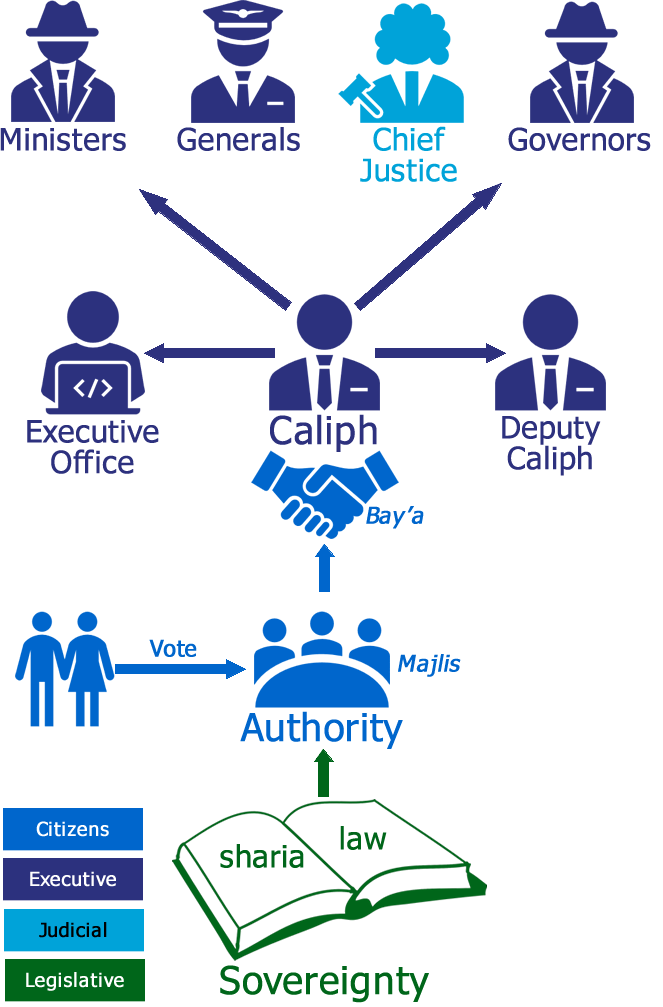

The Islamic State has a unitary executive, where in origin all executive ruling power is with the caliph. This power is transferred to the caliph from the ummah who are the source of authority (مَصْدَر السُلْطَة masdar al-sultah)[1] via the bay’ah contract. Muhammad Haykal says, “The sultah (authority) in Islam belongs to the Ummah and she passes it to the ruler in accordance to a contract (‘aqd) between her and him upon the basis that he rules her by the Kitab of Allah and the Sunnah of His Messenger ﷺ.”[2]

This executive power is not unconditional because it is restricted by the legislative branch of the state which is the shari’a. Allah (Most High) says,

فَٱحْكُم بَيْنَهُم بِمَآ أَنزَلَ ٱللَّهُ

“So judge/rule between them by what Allah has revealed”[3]

The Prophet ﷺ informed us that those who are charged with this responsibility of ruling are the caliphs. He ﷺ said,

كَانَتْ بَنُو إِسْرَائِيلَ تَسُوسُهُمُ الأَنْبِيَاءُ كُلَّمَا هَلَكَ نَبِيٌّ خَلَفَهُ نَبِيٌّ وَإِنَّهُ لاَ نَبِيَّ بَعْدِي وَسَتَكُونُ خُلَفَاءُ فَتَكْثُرُ قَالُوا فَمَا تَأْمُرُنَا قَالَ فُوا بِبَيْعَةِ الأَوَّلِ فَالأَوَّلِ وَأَعْطُوهُمْ حَقَّهُمْ فَإِنَّ اللَّهَ سَائِلُهُمْ عَمَّا اسْتَرْعَاهُمْ

“The prophets ruled over the children of Israel, whenever a prophet died another prophet succeeded him, but there will be no prophet after me. There will soon be caliphs and they will number many.” They asked; “What then do you order us?” He said: “Fulfil the bay’ah to them, one after the other, and give them their dues for Allah will verily account them about what he entrusted them with.”[4]

The Prophet ﷺ described the caliph (imam) as having general powers of responsibility in ruling:

فَالْإِمَامُ الَّذِي عَلَى النَّاسِ رَاعٍ وَهُوَ مَسْئُولٌ عَنْ رَعِيَّتِهِ

“The Imam[5] is a guardian, and he is responsible over his subjects.”[6]

The wording here is mutlaq (unrestricted) so encompasses all types of responsibility over the citizens (رعية). Abdul-Qadeem Zallum (d.2003) comments on this hadith, “This means that all the matters related to the management of the subjects’ affairs is the responsibility of the caliph. He, however reserves the right to delegate anyone with whatever task he deems fit, in analogy with representation (وَكالَة wakala).”[7]

The officials of the state derive their authority from the caliph and are representatives (وُكَلاء wukala’) of him in ruling. Hashim Kamali says, “The head of state, being the wakīl or representative of the community by virtue of a contract of agency/representation thus becomes the repository of all political power. He is authorised, in turn, to delegate his powers to other government office holders, ministers, governors and judges etc. These are, then, entrusted with delegated authority (wilāyat), which they exercise on behalf of the head of state each in their respective capacities.”[8]

Al-Mawardi categorises these representatives into four types:

الْقِسْمُ الْأَوَّلُ: مَنْ تَكُونُ وِلَايَتُهُ عَامَّةً فِي الْأَعْمَالِ الْعَامَّةِ وَهُمْ الْوُزَرَاءُ؛ لِأَنَّهُمْ يُسْتَنَابُونَ فِي جَمِيعِ الْأُمُورِ مِنْ غَيْرِ تَخْصِيصٍ.

(i) those who had general powers over the wilayat (government functions) generally, namely wazirs, who were appointed over all affairs without any special assignment;

وَالْقِسْمُ الثَّانِي: مَنْ تَكُونُ وِلَايَتُهُ عَامَّةً فِي أَعْمَالٍ خَاصَّةٍ، وَهُمْ أُمَرَاءُ الْأَقَالِيمِ وَالْبُلْدَانِ؛ لِأَنَّ النَّظَرَ فِيمَا خُصُّوا بِهِ مِنَ الْأَعْمَالِ عَامٌّ فِي جَمِيعِ الْأُمُورِ.

(ii) those who had general powers in specific wilayat (government functions), namely the amirs of provinces (الأَقالِيم) and districts (البُلْدان), who had the right of supervision of all affairs in the particular area with which they were charged;

وَالْقِسْمُ الثَّالِثُ: مَنْ تَكُونُ وِلَايَتُهُ خَاصَّةً فِي الْأَعْمَالِ الْعَامَّةِ، وَهُمْ كَقَاضِي الْقُضَاةِ وَنَقِيبِ الْجُيُوشِ وَحَامِي الثُّغُورِ وَمُسْتَوْفِي الْخَرَاجِ وَجَابِي الصَّدَقَاتِ؛ لِأَنَّ كُلَّ وَاحِدٍ مِنْهُمْ مَقْصُورٌ عَلَى نَظَرٍ خَاصٍّ فِي جَمِيعِ الْأَعْمَالِ.

(iii) those who had specific powers in the wilayat (government functions) generally, such as the qādī al-qudāt [chief judge], the commander in chief (naqīb al-jaysh), the warden of the frontiers (hāmī al-thughūr), the collector of kharāj, and the collector of sadaqāt; and

وَالْقِسْمُ الرَّابِعُ: مَنْ تَكُونُ وِلَايَتُهُ خَاصَّةً فِي الْأَعْمَالِ الْخَاصَّةِ، وَهُمْ كَقَاضِي بَلَدٍ أَوْ إقْلِيمٍ أَوْ مُسْتَوْفِي خَرَاجِهِ أَوْ جَابِي صَدَقَاتِهِ أَوْ حَامِي ثَغْرِهِ أَوْ نَقِيبِ جُنْدٍ؛ لِأَنَّ كُلَّ وَاحِدٍ مِنْهُمْ خَاصُّ النَّظَرِ مَخْصُوصُ الْعَمَلِ، وَلِكُلِّ وَاحِدٍ مِنْ هَؤُلَاءِ الْوُلَاةِ شُرُوطٌ تَنْعَقِدُ بِهَا وِلَايَتُهُ، وَيَصِحُّ مَعَهَا نَظَرُهُ، وَنَحْنُ نَذْكُرُهَا فِي أَبْوَابِهَا وَمَوَاضِعِهَا بِمَشِيئَةِ اللَّهِ وَتَوْفِيقِهِ

(iv) those who had al-wilāyāt al-khāssa (specific government functions) in specific districts, such as the qādī of a town (بَلَد) or district (إِقْلِيم), the collector of kharāj or sadaqāt of a district, the warden of a specific frontier district or the naqīb of a local military force.”[9]

These four types of officials cover all executive and judicial appointments by the caliph. This provides the flexibility to create as many institutions as are necessary to run the state at any particular period in time.

An important point to note is that the bay’ah contract is to the caliph and not his wakeels. Therefore Al-Mawardi stipulates that the Imam should not over-delegate his authority. He says, “He [Imam] must personally take over the surveillance of affairs and the scrutiny of circumstances such that he may execute the policy of the Ummah and defend the nation without over-reliance on delegation of authority (Al-Tafwid) – by means of which he might devote himself to pleasure-seeking or worship – for even the trustworthy may deceive and counsellors behave dishonestly.”[10]

For the purposes of this discussion, we will be focussing on the second category of appointments namely the amirs of provinces and districts i.e. the governors and mayors.

Devolution can also be seen in the actions of the Prophet ﷺ in his role as a ruler-prophet in Medina. No ruler, not even a prophet can rule a state by himself, so he ﷺ delegated out certain functions to various officials including army commanders, naqibs, governors, judges, tax collectors and scribes as listed above by Al-Mawardi in order to aid in the running of the state.

Notes

[1] Hashim Kamali, ‘Citizenship and Accountability of Government: An Islamic Perspective,’ The Islamic Texts Society, 2011, p.197

[2] Muhammad Khayr Haykal, ‘Al-Jihad wa’l Qital fi as-Siyasa ash-Shar’iyya,’ vol.1, The Eighth Study, Qitaal Mughtasib As-Sultah (Fighting the usurper of the authority)

[3] Holy Qur’an, Surah Al-Ma’ida, ayah 48

[4] Sahih Muslim 1842a, https://sunnah.com/muslim:1842a ; sahih Bukhari 3455, https://sunnah.com/bukhari:3455

[5] Imam here means the khaleefah i.e. the great Imam الْإِمَامُ الْأَعْظَمُ. Ibn Hajar, Fath al Bari, https://shamela.ws/book/1673/7543#p1

[6] Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī 7138, Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim 1829

[7] Abdul-Qadeem Zallum, ‘The Ruling System in Islam,’ translation of Nizam ul-Hukm fil Islam, Khilafah Publications, Fifth Edition, p.111

[8] Hashim Kamali, ‘Separation of powers: An Islamic perspective,’ IAIS Malaysia, p.473; https://icrjournal.org/index.php/icr/article/view/370/348

[9] Ann K. S. Lambton, ‘State and Government in Medieval Islam,’ Oxford University Press, 1981, p.95; Arabic original: https://shamela.ws/book/22881/44

[10] Abu l-Hasan al-Mawardi, The Laws of Islamic Governance, translation of Al-Ahkam as-Sultaniyah, Ta Ha Publishers, p.28, https://shamela.ws/book/22881/35