- The Objective of State and Authority in Islam

- Unity

- Dar Al-Islam

- How is a caliphate divided up?

- The difference between Ikhtilaf (الِاخْتِلاف) and Iftiraq (الاِفْتِراق)

- Five Historical Models of the Caliphate

- The Travels of Ibn Battuta

- Three models of state unity in Islam

- The Unitary State

- Devolution

- Administrative Divisions of the Prophet’s ﷺ State in Medina

- Devolved Powers of the Provinces

- Fully Devolved Powers (Wali ‘Amm)

- Partially devolved powers (Wali Khass)

- The Categorisation of the Provinces by the Historians

- Islamic Society is Devolved

- Areas of Devolution

- Devolution in the Prophet’s ﷺ State

- Devolution in the Rightly Guided Caliphate

- Devolution in the Umayyad Caliphate

- Devolution in the Abbasid Caliphate

- Centralisation vs Decentralisation

- Maintaining a Unitary State

- Shura on Government Appointments

- Removal of Governors

- Provincial Elections

- Election of Amirs in the Prophet’s ﷺ State in Medina

- Election of Amirs in the Rightly Guided Caliphate

- Election of Amirs in the absence of an agreed upon caliph during the civil war

- How would a Unitary State emerge today?

- Conclusion

- Notes

Every state is divided up into administrative divisions in order to organise and manage the local affairs of its citizens. The names and sizes of these divisions will vary between different countries, and an Islamic State or caliphate can use any of these administrative divisions from any system which suits its requirements at the time. The underlying principle here is to keep the caliphate united upon the Islamic ‘aqeeda (creed), even if administratively and politically it consists of separate states and entities.

The top-level division in a caliphate is the province or state known as a Wiliyah (ولاية) or Emirate (إِمَارَةِ). The head of this province is called a Wali or an Amir. In the latter half of the Abbasid Caliphate, when the provinces became powerful semi-independent ‘empires’ then Sultanate (سَلْطَنَة) was used as in the case of the Seljuks, Mamluks and Ottomans.

For the citizens of an Islamic State, their first point of contact with the leadership of the state is the governor of their province or emirate, and their local mayors in the towns and cities. The governor and mayors are managing people’s day to day affairs on a local and regional level. If the governor is oppressive then this affects people’s daily lives more than any other government official including the Caliph. The Messenger of Allah ﷺ said,

مَا مِنْ أَمِيرٍ يَلِي أَمْرَ الْمُسْلِمِينَ ثُمَّ لاَ يَجْهَدُ لَهُمْ وَيَنْصَحُ إِلاَّ لَمْ يَدْخُلْ مَعَهُمُ الْجَنَّةَ

“An Amir who, having obtained control over the affairs of the Muslims, does not strive for their betterment, and does not serve them sincerely shall not enter jannah with them.”[1]

The Objective of State and Authority in Islam

State and authority in Islam is not an end in itself, but a means to an end which is to establish justice so that people can freely worship Allah, fulfil His obligations and refrain from His prohibitions. Allah ta’ala says,

لَقَدْ أَرْسَلْنَا رُسُلَنَا بِٱلْبَيِّنَـٰتِ وَأَنزَلْنَا مَعَهُمُ ٱلْكِتَـٰبَ وَٱلْمِيزَانَ لِيَقُومَ ٱلنَّاسُ بِٱلْقِسْطِ

“We sent Our messengers with clear signs, the Scripture and the Balance, so that people could uphold justice.”[2]

Ibn Ashur (d.1973) explains the meaning of balance (مِيزان) here as “conveying the command to be just (العَدْل) among people. The balance (مِيزان) is a metaphor for justice among people in distributing their rights, as one of the requirements of the balance is the presence of two parties whose equivalence is to be ascertained. Allah ta’ala says, وإذا حَكَمْتُمْ بَيْنَ النّاسِ أنْ تَحْكُمُوا بِالعَدْلِ ‘And when you judge between people, judge with justice.’ [An-Nisa’: 58]”[3]

Aisha Bewley says, “In fiqh, the principal function of government is to enable the individual Muslim to practise the deen and fulfill his obligations to Allah – which, of course, also entails certain societal obligations. This is, at the bottom line, the sole purpose of the state for which purpose alone it is established by Allah, for which purpose alone those in authority possess any authority over others.”[4]

Al-Mawardi (d.1058CE) lists comprehensive justice (عَدْلٌ شَامِلٌ) as one of his six principles of reforming society. He says, “comprehensive justice, results in social harmony and obedience (to the ruler) and makes possible the building of the nation, economic prosperity, population increase and the safety of the ruler. This is why al-Hurmuzan[5] said to Umar when he saw him sleeping with very modest clothes without guards: ‘You practiced justice, earned safety now take a nap (without guards).’

There is nothing that destroys a nation faster, and is more corrupting for the minds of people than injustice because it knows no limits. Every measure sets a pattern of corruption that increases until corruption engulfs everything.”[6]

The question which needs to be addressed in relation to the dividing up and ruling of Dar Al-Islam (lands of Islam), is how unified does a caliphate actually need to be in practice in order to achieve this aim of justice? Many models of unification existed throughout Islamic history from highly centralised unitary models of governance to highly decentralised confederations. In all cases the Islamic civilisation flourished, from the early conquests of the Rightly Guided Caliphs, to the later conquests of the Ottomans who opened Constantinople and Eastern Europe to Islam, but who were not caliphs at the time.

Unity

The concept of Islamic Unity (الوَحْدَة الإِسْلامِيَّة) is heard throughout the Muslim ummah nowadays. This is because of the feeling of helplessness and despair in the face of overwhelming economic and political problems plaguing Muslim countries, while the world superpowers pick them off one by one, eating from them as one would eat from a dish of food. The Gaza Genocide is the most recent of these issues but it is not the first and won’t be the last. The ‘civilised’ west, with all their talk of the rule of law, human rights and the Geneva convention have perpetrated according to Dr Gideon Polya a “Post-9/11 Muslim Holocaust & Muslim Genocide” where 30 million Muslims[7] have been killed in avoidable deaths due to western, or western backed military intervention.

The Prophet ﷺ foretold of this reality.

«يُوشِكُ الأُمَمُ أَنْ تَدَاعَى عَلَيْكُمْ كَمَا تَدَاعَى الأَكَلَةُ إِلَى قَصْعَتِهَا». فَقَالَ قَائِلٌ وَمِنْ قِلَّةٍ نَحْنُ يَوْمَئِذٍ قَالَ «بَلْ أَنْتُمْ يَوْمَئِذٍ كَثِيرٌ وَلَكِنَّكُمْ غُثَاءٌ كَغُثَاءِ السَّيْلِ وَلَيَنْزِعَنَّ اللَّهُ مِنْ صُدُورِ عَدُوِّكُمُ الْمَهَابَةَ مِنْكُمْ وَلَيَقْذِفَنَّ اللَّهُ فِي قُلُوبِكُمُ الْوَهَنَ». فَقَالَ قَائِلٌ يَا رَسُولَ اللَّهِ وَمَا الْوَهَنُ قَالَ «حُبُّ الدُّنْيَا وَكَرَاهِيَةُ الْمَوْتِ»

“The nations will soon summon one another to attack you as people when eating invite others to share their dish.” Someone asked: “Will that be because of our small numbers at that time?” He said: “No, you will be numerous at that time, but you will be scum and rubbish like that carried down by a torrent, and Allah will take fear of you from the breasts of your enemy and cast Al-Wahn[8] into your hearts.” Someone asked: “Oh Messenger of Allah, what is Al-Wahn?” He said: “Love of the world and dislike of death.”[9]

In simple terms, it’s the weakness in the adherence to the Islamic ‘aqeeda and the systems which emanate from it that is the cause of these problems. Disunity and disputes, and the abandonment of Islam are the causes of defeat and fitan (tribulations) in Islam. Allah ta’ala says,

وَأَطِيعُوا۟ ٱللَّهَ وَرَسُولَهُۥ وَلَا تَنَـٰزَعُوا۟ فَتَفْشَلُوا۟ وَتَذْهَبَ رِيحُكُمْ ۖ وَٱصْبِرُوٓا۟ ۚ إِنَّ ٱللَّهَ مَعَ ٱلصَّـٰبِرِينَ

“Obey Allah and His Messenger and do not dispute with one another, or you would be discouraged and weakened. Persevere! Surely Allah is with those who persevere.”[10]

There is no doubt that Islamic unity is a fundamental pillar of an Islamic society. Muhammad Abu Zahrah (d.1974) says, “Islamic unity is a firm truth based on the Qur’anic texts and the hadiths of the Prophet. Islam does not recognize division (الفُرْقَة) based on colour, race, language, or culture.”[11]

Allah ta’ala says,

وَٱعْتَصِمُوا۟ بِحَبْلِ ٱللَّهِ جَمِيعًۭا وَلَا تَفَرَّقُوا۟

And hold firmly together to the rope of Allah and do not be divided. [12]

Rope (حَبْل) here means covenant (الْعَهْدِ), Qur’an and community (الجَماعَة).[13]

Unity brings strength and power and a way to defend against the enemies. The Poet Al-Tughra’i (d.1121CE) famously said,

كونوا جميعاً يا بني إذا أعترى … خطب ولا تتفرقوا أحـادًا

تأبى العصي إذا اجتمعن تكسراَ… وإذا افترقن تكسرت آحادًا

“Be together my sons when trouble strikes, and do not separate as individuals. Sticks refuse to break when they come together, but when they separate, they break individually”[14]

The unchecked hegemony of America post the collapse of the Soviet Union, spurred the global south to establish BRICS as a push back against this hegemony. Many Muslim countries are part of BRICS and others are lining up to join. Military alliances and greater cooperation between Muslim countries are also taking place albeit at a slow pace.

An important question to answer for our time is in which areas do Muslim countries need to be united in order to remain a strong bloc against those enemies who want to steal their lands and resources, and in which areas can they remain divided?

In other words, can we implement a devolved union of states who maintain a high degree of autonomy while at the same time working for some overall common goals such as the defense of Muslim lands and Islamic interests, or are we obliged to maintain a centralised unitary model where an ‘all-powerful’ caliph keeps tight control over all elements of the state?

Dar Al-Islam

Dar ul-Islam is defined as the land which is governed by the laws of Islam, and whose security (amaan أَمان) and protection (man’ah مَنْعَة) are maintained by Muslims, even if the majority of its inhabitants are non-Muslims, as we saw during the Ottoman rule of Eastern Europe. This means internally the government must be implementing Islam, and have full control of its territories i.e. not occupied by foreign forces. Externally, the state should have unrestricted power – within its capability and the international situation – to pursue foreign policy objectives in line with Islam, such as the protection of Muslims and the promotion of Islamic interests.

Muhammad Said Al-Bouti says,

تلتقي كلمة أئمة المذاهب الأربعة على ان البلدة تصبح دار إسلام إذا دخلت في منعة المسلمين وسيادتهم، بحيث يقدرون على إظهار إسلامهم، والامتناع من أعدائهم. فإذا تحققت فيها هذه الصفة بسبب الفتح عنوة أو صلحا أو نحو ذلك. اصبحت دار إسلام، وسرت عليها أحكامها من وجوب الدفاع عنها والقتال دونها، والهجرة إليها، ثم إن هذه الهوية لا تنفك عنها، وإن استولى الأعداء بعد ذلك عليها، فيجيء على المسلمين بذل كل ما يملكونه من جهد للذود عنها وطرد الاعداء منها. وإقامة أحكام الله فيها

“The opinion of the Imams of the four schools of thought agree that a land (dar) becomes a land of Islam (dar al-Islam) if it enters under the protection (man’ah) and sovereignty (siyadah) of the Muslims, such that they are able to show their Islam and resist their enemies. If this characteristic is achieved in it due to conquest by force or peace or something similar, it becomes dar al-Islam, and its rulings apply to it, such as the obligation to defend it, fight for it, and migrate to it.

This identity cannot be separated from it, even if the enemies take control of it after that, so it is up to the Muslims to exert all the effort they possess to defend it and expel the enemies from it, and establish the rulings of Allah in it.”[15]

Dar Al-Islam is a general term which may apply to a caliphate, but also to a semi-independent or even totally independent emirate or sultanate.

How is a caliphate divided up?

A caliphate is essentially a group of emirates, states or provinces which are bound together by the bay’ah ruling contract with its ruler – the caliph. The Caliphate from its initial establishment after the death of the Prophet ﷺ under its first caliph Abu Bakr Al-Siddiq, had always been an ‘empire’ encompassing vast areas of land, and in later periods spanning multiple continents.

In Islamic history the caliphate was broadly divided up into four levels of governance:

| Level | Name | Head |

| 1st Level | Province (ولاية Wiliyah) Emirate (إِمَارَةِ) Sultanate (سَلْطَنَة) | Wali Amir Sultan |

| 2nd Level | District (عمالة I’mala) | ‘Amil Hakim Amir |

| 3rd Level | City (بَلَد Balad) Fortified town (قصبة Qasabah) | Amir Hakim Ra’is |

| 4th Level | Neighbourhood (حَيّ Hayy)[16] Tribe/Clan (قَبِيلَة Qabilah)[17] | Muqaddam Sheikh Naqib |

Administering such a huge state relied heavily on the local governors of the various provinces being loyal, competent and just in their positions. The logistical challenges of ancient communications meant it could take weeks or even months for the governors of Egypt, North Africa, and Khorasan to receive a letter from the caliph. The governor would therefore need to have a great deal of autonomy and authority to manage their province.

Organising these provinces or emirates in to one unified state was no easy task. Initially the Islamic state was a fairly centralised unitary model during the time of the Prophet ﷺ, Abu Bakr and Umar, but then began to unravel in the time of Uthman and Ali leading eventually to the Umayyad dynasty taking over the caliphate, and marking the start of the monarchical (mulk) nature of Islamic rule for the rest of the state’s 1300-year reign.

Ibn Khaldun (d.1406CE) discusses that the Rightly Guided Caliphs “lived in a time when royal authority (mulk) as such did not yet exist, and the restraining influence was religious. Thus, everybody had his restraining influence in himself. Consequently, they appointed the person who was acceptable to Islam, and preferred him over all others. They trusted every aspirant to have his own restraining influence.

After them, from Mu‘âwiyah on, the group feeling (asabiyah) (of the Arabs) approached its final goal, royal authority (mulk). The restraining influence of religion had weakened. The restraining influence of government and group was needed. If, under those circumstances, someone not acceptable to the group had been appointed as successor, such an appointment would have been rejected by it. The (chances of the appointee) would have been quickly demolished, and the community would have been split and torn by dissension.”[18]

How unified a caliphate actually needs to be in practice is a balancing act which requires statesmen who are highly skilled in siyasa sharia such as the Rightly Guided Caliphs. Even then, Uthman and Ali both faced rebellion through no fault of their own, because they governed over human beings who by their nature will sin and oppress others. If they were ‘angels’ then there would be no need for an authority in the first place. The Prophet ﷺ said,

كُلُّ ابْنِ آدَمَ خَطَّاءٌ وَخَيْرُ الْخَطَّائِينَ التَّوَّابُونَ

“All of the children of Adam are sinners, and the best sinners are those who repent.”[19]

Uthman bin Affan said,

إن الله يزع بالسلطان ما لا يزع بالقرآن

“Allah prevents by the authority (sultan) what He does not prevent by the Qur’an.”[20]

What we find in practice is that it is the bond of Islam and the implementation of justice which creates unity, and not a highly centralised authoritarian state. This is especially true when those in power are themselves not implementing justice and abusing their positions, even if they carry Islamic titles like Caliph, Imam, Sultan, Wali or Emir.

Ibn Taymiyyah (d.1328CE) said,

إنَّ اللَّهَ يُقِيمُ الدَّوْلَةَ الْعَادِلَةَ وَإِنْ كَانَتْ كَافِرَةً وَلَا يُقِيمُ الظَّالِمَةَ وَإِنْ كَانَتْ مُسْلِمَةً ويقال الدُّنْيَا تَدُومُ مَعَ الْعَدْلِ وَالْكُفْرِ وَلَا تَدُومُ مَعَ الظُّلْمِ وَالْإِسْلَامِ

“It is said that Allah allows the just state to remain even if it is led by unbelievers, but Allah will not allow the oppressive state to remain even if it is led by Muslims. And it is said that the world will endure with justice and unbelief, but it will not endure with oppression and Islam.”[21]

Al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf (r.694–714CE) was appointed by the Umayyad Caliph Abdul-Malik ibn Al-Marwan (r. 692-705CE) as the governor of Iraq combining both Kufa and Basra. While he was governor, Abdul-Malik’s son, Al-Walid ibn Abdul-Malik (r.705-715CE) appointed Umar ibn Abdul-Aziz as the governor of Medina (r.706-711CE). The Umayyad caliphate at this stage had full territorial integrity and sovereignty over all of its domains, with the central government in Damascus retaining tight control over all the provinces. Such a situation however did not bring unity to the state due to the injustices being committed by some of the governors most notably Al-Hajjaj.

Al-Hajjaj was notorious for his harsh and oppressive rule against the people of Iraq. Ibn Kathir mentions that a man, supposedly by the name of ‘As from the Banu Yashkur tribe, approached Hajjaj and said: “I have been afflicted with a hernia and because of that Bishr bin Marwan (previous governor) excused me and commissioned that I should be granted my maintenance from the Bait ul-Mal.” Upon hearing the man’s claim, al-Hajjaj refused to accommodate it and instead sentenced him to death, and so he was killed. Due to this incident, the people of al-Basrah grew so scared of him that they left the city.[22] The people of Iraq started fleeing to the provinces of Makkah and Madinah under Umar bin Abdul-Aziz’s authority because they knew he was a righteous and just ruler. This angered Hajjaj who wrote to Al-Walid asking for Umar to be expelled from his post as governor. Hajjaj wrote, “It has become apparent that the people of Iraq and Thaqaf are fleeing from Iraq and seeking refuge in al-Madinah and Makkah.”[23] Al-Walid accepted Hajjaj’s advice and dismissed Umar from his post as governor of Medina.

If we fast forward to Al-Andalus, which from 929CE became the Cordoba Caliphate, what we find is unity between the Muslim populations in Spain and those in the lands ruled by the Abbasids, even though ‘legally’ according to the majority on paper they would have been seen as a rebellious entity. It was the Cordoba Caliphate that produced some of the greatest Islamic scholars in history such as, Ibn ‘Abd Rabbih (d.940CE), Ibn Hazm (d.1064CE), Al-Qurtubi (d.1273CE) and Ibn Al-Arabi (d.1240CE).

In the Eastern lands the famous Vizier of the Seljuk Sultanate – Nizam al-Mulk (d.1092CE) established a group of higher education institutions called the Nizamiyyah. These again produced many great scholars and among the professors of these institutions were Imam al-Juwayni (d.1085CE) and Al-Ghazali (d.1111CE). The Seljuk’s never claimed the caliphate for themselves and gave a nominal bay’ah to the Abbasid Caliphs in Baghdad. They were politically disunited from the caliphate as a semi-independent province which in Al-Mawardi’s model falls under the Amir Al-Istila’ (Amir of Conquest) and Wazir Al-Tafweedh (Delegated Assistant).

The difference between Ikhtilaf (الِاخْتِلاف) and Iftiraq (الاِفْتِراق)

An Islamic society is not a one-party communist totalitarian society where differences and individuality are expunged. Human beings differ in their colours, languages, tastes, interests and intellectual capacity. In themselves these differences are not a problem unless they are used to cause dissent and division. Allah ta’ala clearly says in the Qur’an:

يَـٰٓأَيُّهَا ٱلنَّاسُ إِنَّا خَلَقْنَـٰكُم مِّن ذَكَرٍۢ وَأُنثَىٰ وَجَعَلْنَـٰكُمْ شُعُوبًۭا وَقَبَآئِلَ لِتَعَارَفُوٓا۟ ۚ إِنَّ أَكْرَمَكُمْ عِندَ ٱللَّهِ أَتْقَىٰكُمْ ۚ إِنَّ ٱللَّهَ عَلِيمٌ خَبِيرٌۭ

O humanity! Indeed, We created you from a male and a female, and made you into peoples (شُعُوب) and tribes (قَبائِل) so that you may ˹get to˺ know one another. Surely the most noble of you in the sight of Allah is the most righteous among you. Allah is truly All-Knowing, All-Aware.[24]

We need to distinguish between two Arabic words in relation to Islamic unity. They are Ikhtilaf (difference) and Iftiraq (division) which are both found in the Qur’an and Sunnah.

Allah ta’ala says,

وَلَا تَكُونُوا۟ كَٱلَّذِينَ تَفَرَّقُوا۟ وَٱخْتَلَفُوا۟ مِنۢ بَعْدِ مَا جَآءَهُمُ ٱلْبَيِّنَـٰتُ ۚ وَأُو۟لَـٰٓئِكَ لَهُمْ عَذَابٌ عَظِيمٌۭ

“And do not be like those who split (تَفَرَّقُوا) ˹into sects˺ and differed (اِخْتَلَفُوا) after clear proofs had come to them. It is they who will suffer a tremendous punishment.”[25]

Ibn Ashur (d.1973) comments on this splitting and division (الاِفْتِراق):

وفِيهِ إشارَةٌ إلى أنَّ الِاخْتِلافَ المَذْمُومَ والَّذِي يُؤَدِّي إلى الِافْتِراقِ، وهو الِاخْتِلافُ في أُصُولِ الدِّيانَةِ الَّذِي يُفْضِي إلى تَكْفِيرِ بَعْضِ الأُمَّةِ بَعْضًا، أوْ تَفْسِيقِهِ، دُونَ الِاخْتِلافِ في الفُرُوعِ المَبْنِيَّةِ عَلى اخْتِلافِ مَصالِحِ الأُمَّةِ في الأقْطارِ والأعْصارِ، وهو المُعَبِّرُ عَنْهُ بِالِاجْتِهادِ. ونَحْنُ إذا تَقَصَّيْنا تارِيخَ المَذاهِبِ الإسْلامِيَّةِ لا نَجِدُ افْتِراقًا نَشَأ بَيْنَ المُسْلِمِينَ إلّا عَنِ اخْتِلافٍ في العَقائِدِ والأُصُولِ، دُونَ الِاخْتِلافِ في الِاجْتِهادِ في فُرُوعِ الشَّرِيعَةِ.

“The reprehensible differences (الِاخْتِلاف) that leads to division (الاِفْتِراق) is the differences in the fundamentals of religion (usul ad-deen) that leads to some members of the ummah declaring others disbelievers (kafir) or transgressors (fasiq), unlike the differences in the branches (furu’) based on the differences in the interests of the ummah in different countries and eras, which is expressed by ijtihad. If we examine the history of Islamic Schools of Thought (madhāhib), we will not find any division that arose among Muslims except due to differences in ‘aqeeda and usul. We only find differences in ijtihad in the branches of Sharia.”[26]

The Prophet ﷺ said,

افْتَرَقَتِ الْيَهُودُ عَلَى إِحْدَى وَسَبْعِينَ فِرْقَةً فَوَاحِدَةٌ فِي الْجَنَّةِ وَسَبْعُونَ فِي النَّارِ وَافْتَرَقَتِ النَّصَارَى عَلَى ثِنْتَيْنِ وَسَبْعِينَ فِرْقَةً فَإِحْدَى وَسَبْعُونَ فِي النَّارِ وَوَاحِدَةٌ فِي الْجَنَّةِ وَالَّذِي نَفْسُ مُحَمَّدٍ بِيَدِهِ لَتَفْتَرِقَنَّ أُمَّتِي عَلَى ثَلاَثٍ وَسَبْعِينَ فِرْقَةً فَوَاحِدَةٌ فِي الْجَنَّةِ وَثِنْتَانِ وَسَبْعُونَ فِي النَّارِ ” . قِيلَ يَا رَسُولَ اللَّهِ مَنْ هُمْ قَالَ ” الْجَمَاعَةُ

“The Jews split (اِفْتَرَقَت) into seventy-one sects, one of which will be in Paradise and seventy in Hell. The Christians split into seventy-two sects, seventy-one of which will be in Hell and one in Paradise. I swear by the One Whose Hand is the soul of Muhammad, my nation will split into seventy-three sects, one of which will be in Paradise and seventy-two in Hell.” It was said: “O Messenger of Allah, who are they?” He said: “The main body of the ummah (الْجَمَاعَةُ).”[27]

The concept of division (الاِفْتِراق) in the Qur’an often has a negative connotation, referring to divisions, sects, or discord that leads to people straying from the straight path. While the root of the word can also mean “to separate” or “to divide” in a neutral sense (as in the word furqan, meaning criterion or distinction), when used in contexts of human society and religion, it usually implies a fragmentation that is discouraged by Allah.

Ibn ‘Abbas said: “The Aws and the Khazraj had a feud in the pre-Islamic period. One day, they mentioned to each other what had happened in that period and this led them to brandish their swords at each other. Upon being informed of what was happening, the Messenger of Allah ﷺ went to them and these verses were revealed:

وَكَيْفَ تَكْفُرُونَ وَأَنتُمْ تُتْلَىٰ عَلَيْكُمْ ءَايَـٰتُ ٱللَّهِ وَفِيكُمْ رَسُولُهُۥ ۗ وَمَن يَعْتَصِم بِٱللَّهِ فَقَدْ هُدِىَ إِلَىٰ صِرَٰطٍۢ مُّسْتَقِيمٍۢ

يَـٰٓأَيُّهَا ٱلَّذِينَ ءَامَنُوا۟ ٱتَّقُوا۟ ٱللَّهَ حَقَّ تُقَاتِهِۦ وَلَا تَمُوتُنَّ إِلَّا وَأَنتُم مُّسْلِمُونَ

وَٱعْتَصِمُوا۟ بِحَبْلِ ٱللَّهِ جَمِيعًۭا وَلَا تَفَرَّقُوا۟ ۚ وَٱذْكُرُوا۟ نِعْمَتَ ٱللَّهِ عَلَيْكُمْ إِذْ كُنتُمْ أَعْدَآءًۭ فَأَلَّفَ بَيْنَ قُلُوبِكُمْ فَأَصْبَحْتُم بِنِعْمَتِهِۦٓ إِخْوَٰنًۭا وَكُنتُمْ عَلَىٰ شَفَا حُفْرَةٍۢ مِّنَ ٱلنَّارِ فَأَنقَذَكُم مِّنْهَا ۗ كَذَٰلِكَ يُبَيِّنُ ٱللَّهُ لَكُمْ ءَايَـٰتِهِۦ لَعَلَّكُمْ تَهْتَدُونَ

How can you disbelieve when Allah’s revelations are recited to you and His Messenger is in your midst? Whoever holds firmly to Allah is surely guided to the Straight Path.

O believers! Be mindful of Allah in the way He deserves, and do not die except in ˹a state of full˺ submission ˹to Him˺.

And hold firmly together to the rope of Allah and do not be divided. Remember Allah’s favour upon you when you were enemies, then He united your hearts, so you—by His grace—became brothers. And you were at the brink of a fiery pit and He saved you from it. This is how Allah makes His revelations clear to you, so that you may be ˹rightly˺ guided.[28] [29]

While Allah severely condemns this division which nearly led to fighting, they were not reprimanded for remaining in their respective tribes and clans. In fact the Aws and the Khazraj would compete with each other in the good deeds based on the command: فَٱسْتَبِقُوا۟ ٱلْخَيْرَٰتِ “So compete with one another in doing good.”[30]

Ibn Ishaq narrates, “Among the things that Allah did for His Messenger ﷺ was that these two tribes of the Ansar, the Aws and the Khazraj, would compete with the Messenger of Allah ﷺ like two stallions competing. The Aws would not do anything that would please the Messenger of Allah ﷺ except that the Khazraj would say: ‘By Allah, you will not lose any advantage over us by doing this in the eyes of the Messenger of Allah ﷺ and in Islam.’ He said: So they would not stop until they had done something similar. Whenever the Khazraj did something, the Aws would say the same.”[31]

Differences (الِاخْتِلاف) is a general term and in Islamic fiqh has a positive connotation meaning the legitimate differences of opinion that emerge among the ‘ulema when extracting Islamic rules through ijtihad as Ibn Ashur mentioned above.

Therefore, different provinces and states are all fine, but division, fitna, separation and civil war are all unacceptable red-lines in the sharia. The Ummah must remain unified upon the Islamic ‘aqeeda and the agreed upon principles emanating from it. Al-Mawardi lists 10 duties and responsibilities on the caliph the first of which is:

حِفْظُ الدِّينِ عَلَى أُصُولِهِ الْمُسْتَقِرَّةِ، وَمَا أَجْمَعَ عَلَيْهِ سَلَفُ الْأُمَّةِ

“Preserving the deen on its established principles (‘usul) and what the predecessors (salaf) of the ummah have consented upon (‘ijma).”[32]

Five Historical Models of the Caliphate

For most of Islamic history the Caliphate was a decentralised confederation, with executive power held by the various Islamic emirates and sultanates who recognised the caliph through a nominal bay’ah.

Al-Radhi (r.934-940CE) was the last independent Abbasid caliph after the rise of the Buwahids (Buyids) in 934CE, and the establishment of their emirate over Iraq, and central and southern Iran. This reduced the caliph’s executive power to the Dar ul-Khilafah which was a section of Baghdad that housed the Caliphal palace. Al-Khatib (d. 463H,1071CE) mentions that Al-Radhi was “the last of the Caliphs who undertook the sole direction of the army and the finances.”[33] After Al-Radhi, his brother Al-Muttaqi (r.940-944CE) became the caliph and Al-Suyuti says about him that “He had nothing of authority but the name.”[34]

Dr. Ovamir Anjum says, “This third model (940-1517CE) has been called classical Islamic constitutionalism.[35] It is important because, with the exception of the first couple of centuries, it is what the caliphate has actually looked like throughout most of Islamic history.”[36]

| Time period | Dates | Length | Features |

| Rightly Guided Caliphate | 11-41H 632-661 | 30 years | Religious and political authorities were not systematically distinguished |

| Umayyads, Abbasids until Al-Radi | 41-239H 661-940 | 288 years | The caliphate became a primarily political office, and religious authority gradually came to be shared between the caliph and the scholars (ʿulamāʾ). The caliph’s powers had never been absolute in practice, but the ʿulamāʾ began to theorize such limits and functions starting in the fourth/tenth century. |

| Abbasids – Al‐Radi onwards | 329-923H 940-1517 | 600 years | The caliph was primarily a symbolic and spiritual authority; the actual rulers of various provinces were often local governors or invading military commanders who, lacking inherent legitimacy, paid homage to the caliph. These societies were largely self-governed by the Law of Islam as administered by local rulers and scholars. The kings or sultans served as ‘butlers’ or, more grandiosely, as the executive branch, who were important for defense and upkeep of the Law but nevertheless disposable. This third model has been called “classical Islamic constitutionalism”. With the exception of the first couple of centuries, it is what the caliphate has actually looked like throughout most of Islamic history. |

| Ottomans | 923-1326H 1517-1908 | 403 years | The Ottoman sultans (who took on the title “caliph” after defeating the Mamluks in Cairo), upheld the Shariʿa Law that was expounded and administered by the scholars as muftis and judges. The caliph-sultan’s powers, therefore, were limited. We have cases of sultans who were deposed because of the verdict of the chief qadi (judge). |

| 20th Century Ottomans (Young Turks) | 1326-1342H 1908-1924 | 16 years | Western style constitutional caliphate |

The Travels of Ibn Battuta

The famous Morrocco traveller, explorer and scholar – Ibn Battuta (d.1369) chronicled his travels from 1325-1354 at a time when the Abbasid Caliphs in Cairo (1261-1517) were mere figureheads and the entire Muslim world was split into separate sultanates and emirates. Despite this political fragmentation, Ibn Battuta had no problem travelling throughout the lands of Islam from his home under the Marinid Dynasty in Morrocco, to the Emirate of Granada in Spain, across the Mamluk Sultanate which housed the Abbasid Caliphs in Cairo and on to the Delhi Sultanate in India and the Sultanate of the Maldives. On his return journey to Morrocco he stopped off in the Mali Sultanate in sub-Saharan Africa.

In all the places he visited he was welcomed and honoured as a Muslim scholar despite not being a ‘citizen’ of that particular emirate. In fact, Ibn Battuta was appointed to various posts on his travels including a Qadi, Chief Qadi, teacher, ambassador and government advisor. This shows that as long as the underlying principle upon which the emirates and sultanates are based is the Islamic ‘aqeeda, then even in the irregular situation of self-appointed Amirs and different states there will still be a level of unity and cooperation which achieves justice and great achievements for the deen.

Timeline of Ibn Battuta’s Positions

1325–1332 (North Africa, Middle East, Mecca)

- Role: Pilgrim & Student

- Traveled for Hajj and studied Islamic law in Mecca and other learning centers (Cairo, Damascus).

- Gained reputation as a scholar.

1333–1340 (Delhi, India)

- Role: Qāḍī (Judge)

- Appointed by Sultan Muhammad bin Tughluq as a judge in Delhi.

- Held position for several years, enjoyed court life but also faced political intrigue.

1340–1344 (Maldives & Sri Lanka)

- Role: Chief Judge of the Maldives

- Enforced Islamic law in the Maldives, though he often clashed with local customs.

- Married several local women (as was common for visitors of status).

- In Sri Lanka, acted as a respected religious guest, visiting Adam’s Peak.

1345–1346 (China mission attempt)

- Role: Ambassador/Diplomat

- Appointed by Sultan of Delhi to lead a mission to the Mongol Yuan Dynasty in China.

- The mission was delayed, and he traveled by sea through Southeast Asia before reaching China.

- In China, he visited ports and was received as an honored foreign dignitary.

1349–1353 (Return to Morocco & West Africa)

- Role: Scholar & Adviser

- Back in Morocco, shared knowledge of Islamic law and his experiences.

- Later traveled to the Mali Empire (Timbuktu, Gao, Mali), where he served as an adviser and legal authority to Mansa Suleyman.

1354 (Final Years in Morocco)

- Role: Author (via dictation)

- At the request of the Marinid Sultan of Morocco, Ibn Battuta dictated his memoirs to the scholar Ibn Juzayy in Fez.

- This became the famous “al-Riḥla” (The Journey), documenting ~30 years of travel.

Job Timeline Summary

| 1325–1332 | Pilgrim, Student, Scholar. |

| 1333–1340 | Judge in Delhi. |

| 1340–1344 | Chief Judge in Maldives, Religious Guest in Sri Lanka. |

| 1345–1346 | Diplomat/Ambassador (China mission). |

| 1349–1353 | Scholar, Adviser in Mali. |

| 1354 | Author of Rihla |

Three models of state unity in Islam

Broadly speaking there are three models of state unity permitted by the ‘ulema (scholars), which were implemented at various points in Islamic history as Dr. Ovamir Anjum mentions.

| Unitary State | A unitary state is a system of government where a central government holds supreme authority and is the sole sovereign power, with administrative divisions holding devolved powers from the central authority. In this model the bay’ah contract is a citizenship contract. An example is the UK and the Rightly Guided Caliphate of the sahaba. |

| Confederation | A union of independent states that come together for common purposes (like defense or trade), but retain their individual sovereignty. In this model the states give bay’ah to the caliph in return for recognising their territorial sovereignty. An example is the European Union, and the Abbasid Caliphate from the mid-10th century and its relationship with the Buyids and later Seljuks. |

| Commonwealth | A looser union of independent states that cooperate together on common purposes (like defense or trade). There is no bay’ah to a central authority in this model. An example is the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), and the relationship between the 12th century Fatimid ‘Caliphate’ and the Seljuks when confronting the Crusaders. |

In relation to the bay’ah and devolution these three models can be summarised as:

| Model | Bay’ah | Governors | Devolved Powers |

| Unitary State | Bay’ah to caliph | Appointed or elected | General or limited |

| Confederation | Bay’ah to caliph | Elected | General |

| Commonwealth | Bay’ah to leader of their state | Independent | General |

Confederation

The unitary state with devolution is the normative model of Islamic governance which existed from the time of the Prophet ﷺ to the latter half of the Abbasid Caliphate in the mid-10th century CE. After this time the caliphate fragmented and semi-independent emirates and sultanates became the norm. These Amirs and Sultans acknowledged the Abbasid caliph in Baghdad, and gave bay’ah to him in return for the caliph conferring titles and legitimacy on them. Al-Mawardi (d.1058CE) who lived in this period is the one who legitimised the model of a Confederation with his Amir Al-Istila’ (Amir of Seizure or Conquest) and Wazir Al-Tafweedh (Delegated Assistant).

Al-Mawardi legalised the idea of the Amir Al-Istila’ in his model in an attempt to preserve the unity of the caliphate, albeit in name only, and more importantly to preserve the deen which is the objective of an Islamic State in the first place.

Al-Mawardi says, “As for the emirate of seizure or conquest (إمَارَةُ الِاسْتِيلَاءِ Amir Al-Istila’), contracted in compelling circumstances, this occurs when an amir takes possession of a country by force and the caliph entrusts him with this emirate and grants him authority to order and direct it: thus the amir, while acting despotically in his ordering and directing of the emirate by virtue of his conquest, is nevertheless accorded legal sanction by the caliph’s religious duty to transform an irregular situation into a correct one, that is a forbidden one to one which is legally permitted. Even though such practice departs, in its laws and conditions, from what is customary regarding normal appointments, it nevertheless protects the laws of the sharia and upholds the rulings of the deen which may not be allowed to degenerate into disorder or be weakened by corruption. Thus this is permitted in cases of conquest and compelling circumstances, but not in the case of a fitting candidate freely chosen for the appointment – because of the difference which exists between the possibility (to act freely) and incapacity.”[37]

Commonwealth

Rival ‘caliphates’ also emerged in Egypt under the Fatimids and the Cordoba Caliphate in Spain. Although they were political rivals with the Abbasids, and in the case of the Fatimids theological rivals, there was still cooperation and interaction between them especially regarding the hajj, and in the 12th century between the Fatimids and Seljuks against the crusaders. In fact, Salahudin Ayyubi, a Seljuk, was the Vizier of the Fatimid Caliphate from 1169-1171CE before formally abolishing it, and rejoining its lands with the Abbasid caliphate after the death of its last ‘caliph’ Al-Adid (d.1171CE).

Hugh Kennedy explains the context surrounding the establishment of the Cordoba Caliphate under its first ‘caliph’ Abd al-Rahman III. He says, “During ‘Abd al-Rahman’s reign [912 to 929CE] the ‘Abbasid caliphate slid into chaos and the caliphs themselves lost all effective power. Cordoba was very well informed about events in the east and everyone would have been aware of the complete debacle of ‘Abbasid power, which made a mockery of their claims to lead the entire Muslim world.

Events nearer home also had their effect. In 909 the Fatimids, who claimed descent from the Umayyads’ arch-rival, ‘All b. Abi Talib, cousin and son-in-law to the Prophet, had captured Qayrawan, the then capital of Tunisia, and proclaimed themselves caliphs. This suggested that there could indeed be two caliphs at the same time, though the Fatimids, unlike the Umayyads of Spain, did have universal pretensions. If their old enemies could claim the title, should not the Umayyads do so too? The matter was made pressing by the growing influence of the Fatimids in the Maghreb: if the Umayyads were to counter this expansion, they too would have to boast an equal title.”[38]

This irregular situation of multiple imams was addressed by al-Juwaynī (d.1085CE) who permitted it if there was a large distance between the different domains of the Imams. In al-Juwaynī’s time this would be a reference to the Cordoba Caliphate in Spain and the Abbasid Caliphate in the Middle East who had no physical borders between them.

Al-Juwaynī (d.1085CE) says, “If it is possible to appoint a single Imam who implements the plan of Islam and whose vision encompasses all of creation, regardless of their status, in the East and West of the Earth, then his appointment is necessary. In this case, it is not permissible to appoint two Imams. This is agreed upon, and there is no disagreement about it.”[39] He continues, “If what we have mentioned is agreed upon, then some have come to the conclusion that it is permissible to appoint an imam in a country where the imam’s influence does not reach.”[40]

While the classical scholars dealt with the issue of confederation and commonwealth in terms of necessity, and preventing greater disunity and civil war, a contemporary scholar Mohammad Al-Massari has derived the permissibility of these two models directly from the hadith of the Prophet ﷺ. In his book Al-Hijrah he extracts the permissibility from the famous hadith narrated by Buraida which specifies the methodology of expanding the Islamic State.

The Messenger of Allah ﷺ said, “Fight in the name of Allah in the cause of Allah. Fight those who disbelieve in Allah. Fight, but do not commit treason, do not mutilate, and do not kill a child. And when you meet your enemy from among the polytheists, call them to three courses of action. If they respond, accept them and refrain from attacking them.

1- Invite them to (accept) Islam; if they respond to you, accept it from them and desist from fighting against them. Then invite them to migrate from their lands to the land of the Muhajireen and inform them that, if they do so, they shall have all the privileges and obligations of the Muhajireen. [UNITARY SYSTEM]

If they refuse to migrate, tell them that they will have the status of Bedouin (أَعْراب) Muslims and will be subjected to the Commands of Allah like other Muslims, but they will not get any share from the spoils of war or Fai’ except when they actually fight with the Muslims (against the disbelievers). [CONFEDERATION OR COMMONWEALTH]

2- If they refuse to accept Islam, demand from them the Jizya. If they agree to pay, accept it from them and hold off your hands. [AUTONOMOUS COMMUNITIES WITHIN A UNITARY SYSTEM]

3- If they refuse to pay the tax, seek Allah’s help and fight them.”[41]

Al-Massari comments on this hadith:

“If they accept, they are then called to carry the subject or citizen status of Dar ul-Muhajirin (The land of the emigrants) (i.e., the Caliphate state), which represents the best and finest outcome. However, it is not obligatory as they can remain as an independent state or entity, possessing an independent citizenship, where their Dar (land) is Dar Al-Islam, and the rulings of Allah ta’ala which apply upon all believers apply upon them.

They have their own private financial obligations, private Bait ul-Maal (treasury) and public properties located on their territory in terms of the categories of publicly owned properties like oil, gas and valuable minerals etc. They have no right to the Bait ul-Maal (treasury) of the Dar ul-Muhajirin, nor to what is located within that land in terms of public properties like water, oil, gas and valuable minerals etc. That is unless they participate in the fighting or what is similar to that, in which case they would have a share in the Fai’ (booty/spoils of war), or share in something related to the categories of publicly owned properties whether that is in terms of possession or extraction, in which case they would have a share in accordance with what is fair and customary. By greater reason, this applies, word for word, to their relations with every independent land from among the other Muslim Arab (Bedouin) lands.”[42]

He continues, “The changing (or transforming) to Dar ul-Muhajirin” which is exactly the same as joining to become part of the Caliphate state, although being better and recommended, is only a Shar’i right of theirs and not Shar’i Wajib (obligation) upon them. They practise that by their own choice and will and it is not a binding contract which they are not permitted to rescind. This precisely reflects “the right of self-determination”.[43]

In his explanation of Bedouins (Aa’raab) he says, “The “Aa’raab of the Muslims” during the time of the Prophet ﷺ were from the nomadic Bedouin Arabs, the people of the rural land, and none besides them. As for the urban areas of consideration, then besides Al-Madinah they included Makkah and Khaibar. None resided within it (i.e. Makkah) apart from a small number of weak Muslims from those who had legitimate excuses allowing them to remain residing there, or those who were strong and open with their Deen and were not weak or persecuted, such as ‘Umair bin Wahb and Nu’aim bin Abdullah bin An-Nahham, or who had a special permission to remain like Al-‘Abbas bin Al-Muttalib, or someone who was just passing through, the details of which we have explained in other places. The remainder of the inhabitants were disbelievers and were at war against Allah and His Messenger ﷺ until its conquest.

For that reason, Ash-Shaari’ Al-Hakim (The All-Wise Legislator) transferred the wordings: “Aa’raab”, “At-Ta’arrub, and other words derived from the linguistic origin which is synonymous to a great degree to the wordings: “Al-Badw”, “Al-Badaawah” and At-Tabaddiy” which contain some negative overtones indicating harshness, severity, callousness and sternness, to the Shar’i meaning of: “Not carrying the subject status (Taabi’iyah) of Dar ul-Muhajirin.”[44] “Al-Aa’raabiyah” in accordance with the ‘Urf (custom) of the Shaari Al-Hakim (The All-wise Legislator), Glorified be He, the Most High, means: “Not carrying the Taabi’iyah (subject status) of the mother, the subject status of Dar ul-Muhajirin”, and that it does not mean other than this. It has absolutely no relationship to “Al-Badaawah” (Bedouin life), in the case where “Al-Badaawah” reflects a permissible style of living, concerning which there is no problem. Indeed, it could be better for some and preferable for their health and mental and emotional disposition, and All praise belongs to Allah.”[45]

These three models give great flexibility in modern times to create political unity and cooperation between Muslim countries, especially when the normative position of a unitary state is not possible except on a regional level. At a global level the models of confederation and commonwealth are entirely possible to implement in the current age.

The Unitary State

The unitary state is the normative model of Islamic governance. It was first established by the Prophet ﷺ in Medina and its sharia legitimacy is clearly shown in the sunnah of state building. The Rightly Guided Caliphs followed the same model as did the Umayyads and Abbasids until the mid-10th century CE.

Devolution

Devolution is the transfer or delegation of power to a lower level, especially by central government to a local or regional administration. This is different to a federal state where power is shared between states and the central (federal) government. In such a model, provinces have a constitutional right to disobey the central government, and execute their own policies and laws in certain (non-federal) areas. Therefore, in origin the caliphate is a unitary state with devolution and not a federal state even though the differences between the two are small. In the case of America’s federal model, it’s almost identical administratively to how a future caliphate would look i.e. a United States of Islam (USI).

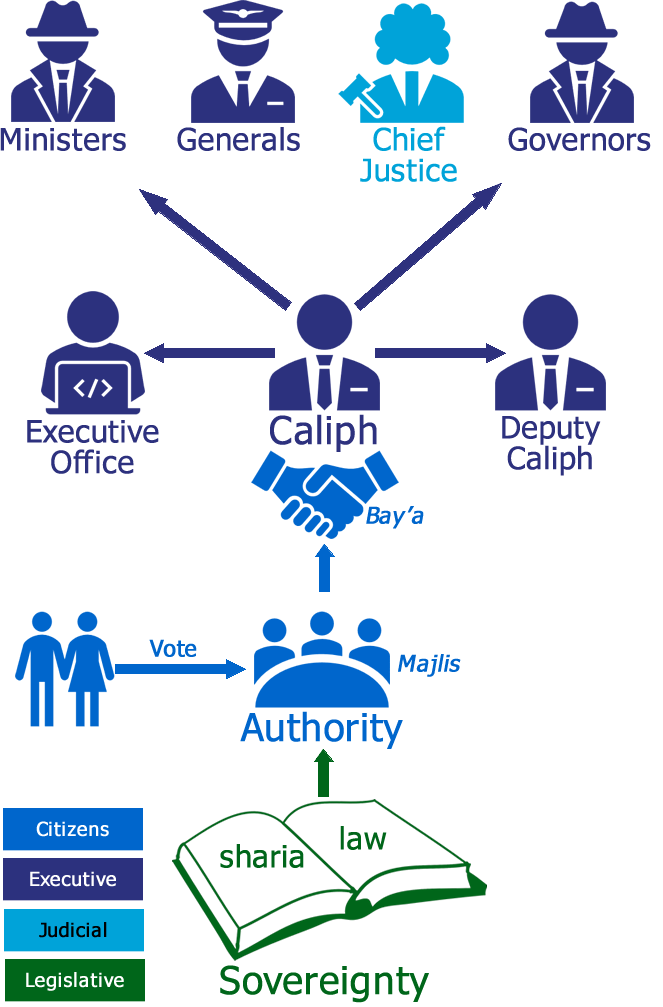

The Islamic State has a unitary executive, where in origin all executive ruling power is with the caliph. This power is transferred to the caliph from the ummah who are the source of authority (مَصْدَر السُلْطَة masdar al-sultah)[46] via the bay’ah contract. Muhammad Haykal says, “The sultah (authority) in Islam belongs to the Ummah and she passes it to the ruler in accordance to a contract (‘aqd) between her and him upon the basis that he rules her by the Kitab of Allah and the Sunnah of His Messenger ﷺ.”[47]

This executive power is not unconditional because it is restricted by the legislative branch of the state which is the shari’a. Allah (Most High) says,

فَٱحْكُم بَيْنَهُم بِمَآ أَنزَلَ ٱللَّهُ

“So judge/rule between them by what Allah has revealed”[48]

The Prophet ﷺ informed us that those who are charged with this responsibility of ruling are the caliphs. He ﷺ said,

كَانَتْ بَنُو إِسْرَائِيلَ تَسُوسُهُمُ الأَنْبِيَاءُ كُلَّمَا هَلَكَ نَبِيٌّ خَلَفَهُ نَبِيٌّ وَإِنَّهُ لاَ نَبِيَّ بَعْدِي وَسَتَكُونُ خُلَفَاءُ فَتَكْثُرُ قَالُوا فَمَا تَأْمُرُنَا قَالَ فُوا بِبَيْعَةِ الأَوَّلِ فَالأَوَّلِ وَأَعْطُوهُمْ حَقَّهُمْ فَإِنَّ اللَّهَ سَائِلُهُمْ عَمَّا اسْتَرْعَاهُمْ

“The prophets ruled over the children of Israel, whenever a prophet died another prophet succeeded him, but there will be no prophet after me. There will soon be caliphs and they will number many.” They asked; “What then do you order us?” He said: “Fulfil the bay’ah to them, one after the other, and give them their dues for Allah will verily account them about what he entrusted them with.”[49]

The Prophet ﷺ described the caliph (imam) as having general powers of responsibility in ruling:

فَالْإِمَامُ الَّذِي عَلَى النَّاسِ رَاعٍ وَهُوَ مَسْئُولٌ عَنْ رَعِيَّتِهِ

“The Imam[50] is a guardian, and he is responsible over his subjects.”[51]

The wording here is mutlaq (unrestricted) so encompasses all types of responsibility over the citizens (رعية). Abdul-Qadeem Zallum (d.2003) comments on this hadith, “This means that all the matters related to the management of the subjects’ affairs is the responsibility of the caliph. He, however reserves the right to delegate anyone with whatever task he deems fit, in analogy with representation (وَكالَة wakala).”[52]

The officials of the state derive their authority from the caliph and are representatives (وُكَلاء wukala’) of him in ruling. Hashim Kamali says, “The head of state, being the wakīl or representative of the community by virtue of a contract of agency/representation thus becomes the repository of all political power. He is authorised, in turn, to delegate his powers to other government office holders, ministers, governors and judges etc. These are, then, entrusted with delegated authority (wilāyat), which they exercise on behalf of the head of state each in their respective capacities.”[53]

Al-Mawardi categorises these representatives into four types:

الْقِسْمُ الْأَوَّلُ: مَنْ تَكُونُ وِلَايَتُهُ عَامَّةً فِي الْأَعْمَالِ الْعَامَّةِ وَهُمْ الْوُزَرَاءُ؛ لِأَنَّهُمْ يُسْتَنَابُونَ فِي جَمِيعِ الْأُمُورِ مِنْ غَيْرِ تَخْصِيصٍ.

(i) those who had general powers over the wilayat (government functions) generally, namely wazirs, who were appointed over all affairs without any special assignment;

وَالْقِسْمُ الثَّانِي: مَنْ تَكُونُ وِلَايَتُهُ عَامَّةً فِي أَعْمَالٍ خَاصَّةٍ، وَهُمْ أُمَرَاءُ الْأَقَالِيمِ وَالْبُلْدَانِ؛ لِأَنَّ النَّظَرَ فِيمَا خُصُّوا بِهِ مِنَ الْأَعْمَالِ عَامٌّ فِي جَمِيعِ الْأُمُورِ.

(ii) those who had general powers in specific wilayat (government functions), namely the amirs of provinces (الأَقالِيم) and districts (البُلْدان), who had the right of supervision of all affairs in the particular area with which they were charged;

وَالْقِسْمُ الثَّالِثُ: مَنْ تَكُونُ وِلَايَتُهُ خَاصَّةً فِي الْأَعْمَالِ الْعَامَّةِ، وَهُمْ كَقَاضِي الْقُضَاةِ وَنَقِيبِ الْجُيُوشِ وَحَامِي الثُّغُورِ وَمُسْتَوْفِي الْخَرَاجِ وَجَابِي الصَّدَقَاتِ؛ لِأَنَّ كُلَّ وَاحِدٍ مِنْهُمْ مَقْصُورٌ عَلَى نَظَرٍ خَاصٍّ فِي جَمِيعِ الْأَعْمَالِ.

(iii) those who had specific powers in the wilayat (government functions) generally, such as the qādī al-qudāt [chief judge], the commander in chief (naqīb al-jaysh), the warden of the frontiers (hāmī al-thughūr), the collector of kharāj, and the collector of sadaqāt; and

وَالْقِسْمُ الرَّابِعُ: مَنْ تَكُونُ وِلَايَتُهُ خَاصَّةً فِي الْأَعْمَالِ الْخَاصَّةِ، وَهُمْ كَقَاضِي بَلَدٍ أَوْ إقْلِيمٍ أَوْ مُسْتَوْفِي خَرَاجِهِ أَوْ جَابِي صَدَقَاتِهِ أَوْ حَامِي ثَغْرِهِ أَوْ نَقِيبِ جُنْدٍ؛ لِأَنَّ كُلَّ وَاحِدٍ مِنْهُمْ خَاصُّ النَّظَرِ مَخْصُوصُ الْعَمَلِ، وَلِكُلِّ وَاحِدٍ مِنْ هَؤُلَاءِ الْوُلَاةِ شُرُوطٌ تَنْعَقِدُ بِهَا وِلَايَتُهُ، وَيَصِحُّ مَعَهَا نَظَرُهُ، وَنَحْنُ نَذْكُرُهَا فِي أَبْوَابِهَا وَمَوَاضِعِهَا بِمَشِيئَةِ اللَّهِ وَتَوْفِيقِهِ

(iv) those who had al-wilāyāt al-khāssa (specific government functions) in specific districts, such as the qādī of a town (بَلَد) or district (إِقْلِيم), the collector of kharāj or sadaqāt of a district, the warden of a specific frontier district or the naqīb of a local military force.”[54]

These four types of officials cover all executive and judicial appointments by the caliph. This provides the flexibility to create as many institutions as are necessary to run the state at any particular period in time.

An important point to note is that the bay’ah contract is to the caliph and not his wakeels. Therefore Al-Mawardi stipulates that the Imam should not over-delegate his authority. He says, “He [Imam] must personally take over the surveillance of affairs and the scrutiny of circumstances such that he may execute the policy of the Ummah and defend the nation without over-reliance on delegation of authority (Al-Tafwid) – by means of which he might devote himself to pleasure-seeking or worship – for even the trustworthy may deceive and counsellors behave dishonestly.”[55]

For the purposes of this discussion, we will be focussing on the second category of appointments namely the amirs of provinces and districts i.e. the governors and mayors.

Devolution can also be seen in the actions of the Prophet ﷺ in his role as a ruler-prophet in Medina. No ruler, not even a prophet can rule a state by himself, so he ﷺ delegated out certain functions to various officials including army commanders, naqibs, governors, judges, tax collectors and scribes as listed above by Al-Mawardi in order to aid in the running of the state.

Administrative Divisions of the Prophet’s ﷺ State in Medina

The sunnah consists of the speech, actions and consent of the Prophet ﷺ. It is a fundamental source of Islamic Law (sharia) from which we guide our actions.[56] The sunnah is not just restricted to ‘ibadat (worships) but covers all aspects of life, state and society. Allah ta’ala says,

وَمَآ ءَاتَىٰكُمُ ٱلرَّسُولُ فَخُذُوهُ وَمَا نَهَىٰكُمْ عَنْهُ فَٱنتَهُوا۟

“Whatever the Messenger gives you, take it. And whatever he forbids you from, leave it.”[57]

The relative pronoun (مَا) is ‘aam (general) and means “whatever” so we do not restrict the sunnah to one sphere of life only. Today siyasa sharia (Islamic politics) is a neglected sunnah and an area which requires greater scrutiny and study to guide us through the maze of modern political life.

In regards to the Islamic ruling system, the speech and actions of the Prophet ﷺ in Medina related to government are a divine evidence (شَرْع دَلِيل shara’ daleel) for us to follow.

The 12 Naqibs

When the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ first established the state in Medina, the existing tribal structure was used to administer the state. The Aws and Khazraj tribes whom Islam united together as the Ansar (helpers), were sub-divided into various clans who managed their own administrative affairs as devolved ‘mini-provinces’.

The chiefs (naqibs) of these clans were not appointed by the Prophet ﷺ, but rather ‘elected’ by the tribes themselves on his ﷺ orders. Ka’b ibn Malik narrates that the Prophet ﷺ said,

أَخْرِجُوا إلَيَّ مِنْكُمْ اثْنَيْ عَشَرَ نَقِيبًا، لِيَكُونُوا عَلَى قَوْمِهِمْ بِمَا فِيهِمْ. فَأَخْرَجُوا مِنْهُمْ اثْنَيْ عَشَرَ نَقِيبًا، تِسْعَةً مِنْ الْخَزْرَجِ، وَثَلَاثَةً مِنْ الْأَوْسِ.

أَسَمَاءُ النُّقَبَاءِ الِاثْنَيْ عَشَرَ وَتَمَامُ خَبَرِ الْعَقَبَةِ

“Bring out to me from among you twelve chiefs (naqibs), so that they may be in charge of their people and whatever is in them.” So they brought out from among them twelve chiefs, nine from the Khazraj, and three from the Aws.[58]

He ﷺ said to the Naqibs:

أنتم على قومكم بما فيهم كفلاء ككفالة الحواريين لعيسى بن مريم، وأنا كفيل على قومي

“You are responsible for your people and what is in them, just as the disciples were responsible for Jesus, son of Mary. I am responsible for my people.”[59]

“The Naqib means: عريفُ القوم يتعرف أخبارهم وينقب “the leader (‘arif) of the people who learns their news and investigates.”[60]

Al-Asamm (d. 852 CE) says,

هُمُ المَنظُورُ إلَيْهِمْ والمُسْنَدُ إلَيْهِمْ أُمُورُ القَوْمِ وتَدْبِيرُ مَصالِحِهِمْ

“They (naqibs) are the ones who are looked to and entrusted with the affairs of the people and the management of their interests.”[61]

The 12 Naqibs[62]

| No. | Name | Tribe | Service to Islam |

| 1 | Abu Umama As’ad bin Zurara | Khazraj | Died before Badr. One of the original six who became Muslim at hajj one year before. |

| 2 | Rafi’ bin Malik | Khazraj | One of the original six who became Muslim at hajj one year before. |

| 3 | Ubada ibn al-Samit | Khazraj | Commander at Badr. Teacher and Judge in Ash-Sham under Umar ibn Al-Khattab. |

| 4 | Sa’d bin al-Rabi’ | Khazraj | Battle of Badr, martyred at Uhud |

| 5 | Abd Allah bin Rawaha | Khazraj | Battles of Badr, Uhud, Khandaq. Commander of the Battle of Mu’tah where he was martyred. |

| 6 | al-Bara’ bin Ma’rur | Khazraj | First to give 2nd bay’ah of Aqaba. He died before the arrival of the Prophet ﷺ in Medina. |

| 7 | Abd Allah bin ‘Amr bin Haram | Khazraj | Battle of Badr, martyred at Uhud |

| 8 | Sa’d ibn Ubadah | Khazraj | Candidate for post of Caliph at the Saqifah of his clan after Prophet’s ﷺ death. |

| 9 | al-Mundhir bin ‘Amr | Khazraj | Battles of Badr, Uhud. Commander at Bi’r Ma’una where he was martyred. |

| 10 | Usaid bin Hudair | Aws | Commander of Aws at Uhud, Hunayn and Tabuk. Part of bay’ah contract to Abu Bakr at the Saqifah. |

| 11 | Sa’d ibn Khaithamah | Aws | Martyred at Badr |

| 12 | Rifa’ah ibn ‘Abd al-Mundhir ibn Zunayr | Aws | Battle of Badr |

Sahifat al-Medina

Early in the formation of the state, the Prophet ﷺ drew up a charter called the Sahifat al-Medina, which was similar to a modern-day constitution. This document defined the relationships and responsibilities of the various tribes in Medina who made up the Islamic society. Muhammad Al-Massari says, “We also observe, through a mere reading of the Sahifa, that it represents, in its sum, constitutional texts which regulate the relationship between the different groups of a society which has been formed upon a tribal basis, where tribes represent important units and each tribe is equivalent to a state.”[63]

The Sahifa treaty “mentioned 40 subtribes or clans by name, and stated that each tribe will carry the responsibilities of its members; they will oversee their own blood-money disputes, prisoners of war, and the poor and needy.”[64] In other words the Prophet ﷺ devolved some ruling powers to these clans a process known in modern times as devolution.

An example of one of these clauses is Banu Sa‘ida, a sub-tribe of Khazraj headed by Sa’d ibn Ubadah, where the famous bay’ah to Abu Bakr was conducted after the Prophet’s ﷺ death. The Sahifa stated:

“Banu Sa‘ida shall be responsible for their own ward (مَعاقِلهم), and shall pay their blood-money in mutual collaboration and every group shall secure the release of its own prisoners by paying their ransom from themselves, so that the dealings between the believers be in accordance with the principles of goodness and justice.”[65]

It is clear from the Sahifa and the command of the Prophet ﷺ: أَخْرِجُوا إلَيَّ مِنْكُمْ اثْنَيْ عَشَرَ نَقِيبًا، لِيَكُونُوا عَلَى قَوْمِهِمْ بِمَا فِيهِمْ “Bring out to me from among you twelve chiefs (naqibs), so that they may be in charge of their people and whatever is in them,” that these naqibs had full powers over their clans as indicated by the relative pronoun (مَا) which is ‘aam (general) and means “whatever”. This is an evidence (شَرْع دَلِيل shara’ daleel) for elected governors as we will discuss in due course.

Since these naqibs were only amirs of a clan (district in modern speak), their powers would exclude anything to do with policies related to the common security and well-being of the state such as taxation and military expeditions. The sub-tribes would assist in these common issues such as participation in the battles as the Sahifa constitution of Medina outlined, but they would have no autonomy to pursue their own agendas separate to that of the Prophet ﷺ. No military expedition ever took place without the direct command and consent of the Prophet ﷺ who was the commander-in-chief, except that of Abu Basir who was outside the authority and jurisdiction of the Prophet’s ﷺ state at the time. The Sahifa states:

وَإِنَّهُمْ يَنْصُرُونَ بَعْضُهُمْ بَعْضًا عَلَى مَنْ دَهَمَ يَثْرِبَ

“And they (the signatories) support one another against whoever attacks Yathrib [Medina].”[66]

Al-Aws and Al-Khazraj (Ansar)

Prior to Islam, Sa’d ibn Mu’adh and Usaid bin Hudair were the chiefs (sayyid) of Banu Abd Al-Ashhal, a sub-tribe of Al-Aws.[67] Although Usaid bin Hudair was the ‘elected’ Naqib of Banu Abd Al-Ashhal, Sa’d ibn Mu’adh was the overall leader of Al-Aws. Sa’d ibn Ubadah, the Naqib of Banu Sa‘ida was the overall leader of Al-Khazraj[68], and both Sa’ds would represent the opinions of the Ansar as a whole. After the Prophet ﷺ passed away the Ansar’s candidate for the caliphate was Sa’d ibn Ubadah, and the bay’ah took place at his Saqifa (portico) because Sa’d ibn Mu’adh had passed away after the Battle of Khandaq in 5 Hijri.

At the Battle of Badr, Sa’d ibn Mu’adh carried the flag (liwaa’) of Al-Aws and since Sa’d ibn Ubadah was back in Medina protecting the city, Sa’d ibn Mu’adh represented the opinion of the entire Ansar, both Al-Aws and Al-Khazraj. Before the battle the Prophet ﷺ said to the sahaba, “Advise me, people!” When the Messenger of Allah ﷺ said that, Sa’d ibn Mu’adh said to him: “By Allah, it seems that you mean us [Ansar], O Messenger of Allah?” He ﷺ said: “Yes.”[69]

After the expedition of al-Muraysī’ in 627CE (5 AH), the munafiqun (hypocrites) concocted a malicious slander (ifk) against ‘Aisha (ra), the mother of the believers, and beloved wife of the Prophet ﷺ. The head of the munafiqun was Abd Allah ibn Ubayy ibn Salul, who was one of the prominent members of Al-Khazraj. The Prophet ﷺ gathered the Muslims in the Masjid and delivered a sermon exposing Abd Allah ibn Ubayy’s lies. Sa’d ibn Mu’adh of Al-Aws, stood up and said if he was from his tribe i.e. Al-Aws then he would execute him. However, if he was from another tribe (state) in this case Al-Khazraj, then he would need permission to do that since he had no authority over Al-Khazraj. This is an indication of the administrative setup and devolved powers of the various tribes of Medina.

‘Aisha narrates that the Messenger of Allah ﷺ addressed the sahaba in the Masjid saying, “O group of Muslims, who will excuse me from a man who has harmed my family? I have been informed about him. By Allah, I have never known anything about my family except good. They have mentioned a man about whom I have never known anything except good, and he never enters upon my family except with me.” She said, then Sa’d ibn Muadh, the brother of Banu Abd al-Ashhal, said: “O Messenger of Allah, I excuse you. If he is from Al-Aws, I will strike his neck, and if he is from our brothers from Al-Khazraj, you order us and we will do what you order.”[70]

Jewish Tribes

The tribes of Medina were not just Muslim. There were a number of Jewish tribes, and they also managed their own affairs except in matters of common security and disputes with the Muslims. “The treaty clarified that the Jewish nation is responsible for all its internal affairs, such as internal disputes, blood-money, and the poor and needy, as aforementioned. However, if there are disputes between the two nations (i.e., the Jews and Muslims), it will be deferred to the judgement of the Prophet ﷺ. The Jews therefore enjoyed semi-independent statehood within the Islamic state.”[71]

The Prophet ﷺ did not appoint separate Amirs over the Jewish tribes, or establish mosques within them, or force Muslims to move and live among them. This clearly shows that there was no agenda to dilute or pressure these communities to ‘Islamicise’ in a religious and cultural sense. Only in relation to the common security and overarching interests of the state, were they obliged to obey the Prophet ﷺ, something they renegaded on time after time jeopardising the security of Medina and leading to their eventual expulsion from Hejaz. The Sahifa states:

وَإِنَّ الْيَهُودَ يُنْفِقُونَ مَعَ الْمُؤْمِنِينَ مَا دَامُوا مُحَارَبِينَ

“And the Jews spend with the believers as long as they are at war.”[72]

This independence of the dhimmi (non-Muslim citizens) in their religious and communal matters continued throughout the caliphate’s history, and old churches and synagogues can still be seen to this day in the Christian and Jewish quarters of many Muslim countries.

This use of the tribal structure to administer the state on a local level continued throughout the lifetime of the Prophet ﷺ.

The First Major Province

After the Treaty of Hudaibiyah (628CE/6Hijri), the state dramatically expanded, and the city-state model transformed into an ‘empire’ model where vast regions of Arabia became part of the Islamic State. The first of these new territories was Yemen under Bādhān ibn Sāsān the former Persian governor. Yemen was the first major province (wiliyah) of the state with Bādhān its first appointed governor (wali). The Wali or Amir as he was more commonly known, would be the top-level official in the province with the tribal chiefs operating at a local level beneath him. The Amir would never interfere in the local affairs of the tribes or appoint their heads. It was left to the members of the tribe to ‘elect’ or consent to whomever they wished to be their tribal chief.

Devolved Powers of the Provinces

Al-Mawardi says, “If the caliph appoints an amir over a district (إِقْلِيم iqleem) or a town (بَلَد balad), his emirate may be one of two kinds, either general (عامَّة ‘amma) or particular (خاصَّة khassa).”[73]

A general emirate is one where the governor has full devolved powers over all aspects of his province including the army[74], finance, judiciary, education and so on. This type of governor is known as a والِي عامّ Wali ‘Amm. This is a decentralised model and in Al-Mawardi’s structure where he assigns devolved powers to the military, is more akin to a confederation than a unitary state. In the general emirates of the Prophet ﷺ and the Rightly Guided Caliphs, the provinces never had powers over the army independent of the commander-in-chief i.e. the head of state.

A governor can also be appointed with limited devolved powers over his province while the central caliphate government controls the rest. Historically, separate judges, finance officials, police chiefs and teachers were appointed over some of the provinces at the discretion of the caliph. This type of governor is known as a والِي خاصّ Wali Khass. This is a more centralised model in line with the traditional notion of a unitary state.

Both of these types of governor were appointed by the Prophet ﷺ and the Rightly Guided Caliphs after them.

Fully Devolved Powers (Wali ‘Amm)

Al-Mawardi says, “As for emirate which has been specifically and freely assigned, it comprises a clearly defined task and a clearly determined jurisdiction: the caliph delegates the emirate of a country or province to the person appointed for this task and accords the right of governance over all its people together with jurisdiction over the customary acts of his office: he thus assumes a general responsibility for a particular territory and for specific and clearly defined tasks, and his corresponding jurisdiction covers seven matters:

1- The ordering of the armies, assigning them to various territories and apportioning their provisions, unless the caliph has fixed the amount of provision in which case the amir has only to ensure its payment to them.

2- Application of the law and the appointment of judges (الْقُضَاةِ) and magistrates (الْحُكَّامِ).

3- Collection of the kharaj and zakah taxes, appointment of collectors, and distribution of what is collected to those entitled to it.

4- Protection of the deen, defence of what is inviolable and the guarding of the deen from modification and deviation.

5- Establishment of the hadd-punishments both with respect to Allah’s rights and those of people.

6- Imamate of the Juma’h gatherings and prayer assembly, he himself acting as Imam or his substitute.

7- Facilitating the passage of hajjis from his territory or those of other territories such that he affords them protection.

8- If this province is a border territory adjacent to the enemy, an eighth matter becomes obligatory, that is jihad against the neighbouring enemy, and distribution of the booty amongst the fighters after a fifth has been taken for those entitled to it.

The conditions considered in this emirate are the same as those applicable in the ministry of delegation (Wizarah Al-Tafwid) as the only difference between the two is that there is specific authority (الولاية) in the former but a general one in the latter, there being no difference in the conditions applicable to specific or general authorities.”[75]

Partially devolved powers (Wali Khass)

In origin, the caliph can devolve any of his executive powers to the governors. Al-Mawardi says, “The Specific Emirate refers to that in which the amir is restricted to organisation of the army, establishment of public order, defence of the territory and protection of what is inviolable; it is not, however, up to him to undertake responsibility for the judiciary and the rulings of jurisprudence, or for the kharaj and zakah.”[76]

The Categorisation of the Provinces by the Historians

The historians such as Al-Tabari (d.923CE) and Al-Kindi (d.961CE) referred to a governor with full powers over his province (Wali ‘Amm) as a Wali Al-Salah wa Al-Kharaj (Governor of prayer and tax) where salah (prayer) is a metaphor (كِنايَة kiniya) for the deen (religion) i.e. implementation of Islam[77] and kharaj (tax) is a metaphor for control of the treasury (Bait ul-Mal) and the funds of the state.

Al-Kindi in the introduction to his book Kitab Al-Wulah wa Kitab Al-Qudah (The Book of Governors and the Book of Judges) says, “This is a book naming the governors (وُلاة Wulah) of Egypt, and those who were in charge of prayer (والِي الصَلاَة Wali Al-Salah), and those who were in charge of war and the police (ولِيَ الحرب والشُّرطة Wali Al-Harb wa Al-Shurta)[78] since it was conquered until our time, and those for whom prayer and tax were combined (والِي الصَلاَة والخَراج Wali Al-Salah wa Al-Kharaj) in the name of Allah and with His help, and may Allah’s prayers be upon Muhammad and his family.”[79]

Al-Tabari narrates that in the year 66H/685CE Abdullah ibn Al-Zubayr appointed Abdullah ibn Muti’ as his governor over Kufah in Iraq. He appointed him as an Amir with general jurisdiction over his province: وأقام ابن مطيع على الكوفة على الصلاة والخراج “Ibn Mut’i’ was appointed governor of Kufa to oversee the salah and the kharaj.”[80]

It was known by convention from the time of the Prophet ﷺ that leading the salah implied more than simply praying. Allah (Most High) says,

قَالُوا۟ يَـٰشُعَيْبُ أَصَلَوٰتُكَ تَأْمُرُكَ أَن نَّتْرُكَ مَا يَعْبُدُ ءَابَآؤُنَآ أَوْ أَن نَّفْعَلَ فِىٓ أَمْوَٰلِنَا مَا نَشَـٰٓؤُا۟ ۖ إِنَّكَ لَأَنتَ ٱلْحَلِيمُ ٱلرَّشِيدُ

They said, ‘Shuayb, does your prayer (salah) tell you that we should abandon what our forefathers worshipped and refrain from doing whatever we please with our own property? Indeed you are a tolerant and sensible man.’[81]

Al-Razi (d.925CE) comments on this verse and mentions one of the opinions of the ‘ulema is that salah is a metaphor (كِنايَة kiniya) for the deen.

المُرادُ مِنهُ الدِّينُ والإيمانُ؛ لِأنَّ الصَّلاةَ أظْهَرُ شِعارِ الدِّينِ، فَجَعَلُوا ذِكْرَ الصَّلاةِ كِنايَةً عَنِ الدِّينِ

“What is meant by it [salah] is deen and iman, because prayer is the most obvious symbol of the deen, so they made the mention of prayer a metaphor for the deen.”[82]

This is based on the hadith of the Prophet ﷺ where he said, الصلاة عمود الدين “Prayer is the pillar of the deen.”[83] In another narration, أْسُ الأَمْرِ الإِسْلاَمُ وَعَمُودُهُ الصَّلاَةُ وَذِرْوَةُ سَنَامِهِ الْجِهَادُ “The head of the matter is Islam, and its pillar is the prayer, and its peak is Jihad.”[84]

Abdullah ibn Mas’ud narrates that, when the Messenger of Allah ﷺ died, the people of the Ansar said, “Let there be two rulers: one that will be chosen from among us (the Ansar), and one that will be chosen from among you (i.e., from among the Muhajirun).” Umar went to them and said, “O people of the Ansar, don’t you know that the Messenger of Allah ﷺ ordered Abu Bakr to lead the people in prayer. So which one of you would be pleased with himself if he were to be placed ahead of Abu Bakr (in ranking or status)?” The people of the Ansar responded, “We seek refuge from being placed ahead of Abu Bakr.”[85] Umar used Abu Bakr’s imamate of salah as an argument in favour of him becoming the Imam of the Islamic State i.e. the caliph.

Islamic Society is Devolved

An important point to note is that the Islamic state is not a communist state where the regime is in control over all aspects of social, political and economic life. The governing authority in Islam certainly plays a major role in society, but it does not intrude into the individual and family affairs of people unless people are facing abuse and harm in these spheres and need protection. In essence an Islamic society is already devolved in terms of its responsibilities. The family plays a pivotal role in looking after its members both young and old, not just in terms of financial support but also with regards the children, educating them and bringing them up to be functioning members of the society.

Communities and neighbourhoods are simply a collection of families and so will manage their affairs in a similar manner. The Islamic charitable endowment known as Waqf where an individual or institution permanently donates assets, such as land or money, for religious, charitable, or social purposes to benefit the community, meant that many local projects such as new mosques, schools, hospitals, guilds, homes, wells, orchards etc were developed and supported separate to the state. This tradition continues to this day and is known as Sadaqa Jariya, a charity that continues to give reward even after one’s death.

In western countries the benefits bill in terms of social care, pensions and other social security handouts is huge. In the UK it accounts for around 25% of the total government spend which in 2022-2023 equated to £300 billion.[86] The Islamic policy in origin is for the families to manage this. Instead of taxing working age adults in order to pay the money back to them in the form of pensions when they are old or out of work, this financial burden will be on the family. Since they pay less tax, then they have greater disposal income to support this. No doubt such a system requires a very different kind of society to the individualistic liberal societies of the west.

Areas of Devolution

When examining the devolved powers to the governors we find three main areas in which the governors generally had no control, although there were exceptions as we will come to. These areas are the army, finance (taxation) and judiciary. Limiting the powers of the governor in any of these fields would mean that the power is not devolved and hence is centralised under the central caliphal government via a separate army commander, ‘Amil (tax collector) and Qadi (judge). In modern times this is via separate government departments headed by a minister or secretary.

The central caliphal government in principle can centralise or devolve any of its executive powers as it deems fit for the time, and is not limited to just the army, finance and judiciary. Education was always the preserve of the ‘ulema and their respective madhhabs (schools of thought) where scholars graduated through a system of ijaza (authorisation).[87]

The Abbasids did establish hospitals but generally local doctors and healers would administer health care to the tribes and community. The caliphs would have their own personal physicians and in many cases these weren’t Muslim. Moses Hamon, for example, who after fleeing Spain with his father, became the physician for the Ottoman Caliph – Suleiman the Magnificent.

Recently, the thinktank ‘Labour Together’ produced a report outlining a policy of devolving powers over education, health and some aspects of criminal justice to local mayors which was endorsed by the UK government’s local government secretary Steve Reed.[88]

In terms of collective ibadat (worship) Al-Mawardi says, “Some say that leading the prayers on Fridays and the Eid days is the responsibility of the judiciary rather than that of the amir, and this is the most convincing opinion for the followers of ash-Shafi’i, although it has also been said that the amirs are more entitled to it, and this is the most convincing view for the Hanafis.”[89] The ‘ulema who made up the judiciary generally had this responsibility through the entire Islamic State. They were effectively an independent institution who managed their own affairs and madrassas unless appointed as official judges or professors by the state.

The Army

Al-Mawardi says, “If the territorial authority of this type of amir (Wali Khass) lies adjacent to a border he may not initiate a jihad except with the Caliph’s permission, although he must wage war on them and repulse them if they initiate the attack, without the Caliph’s permission, as this forms part of his duty to protect and defend what is inviolable.”[90]

In a unitary state, the armed forces are all unified under the caliph who is the Commander-in-Chief. He has the sole power to declare war and despatch the military. Philip Hitti (d.1978) says, “The army was the ummah, the whole nation, in action. Its amir or commander in chief was the caliph in al-Madinah, who delegated the authority to his lieutenants or generals.”[91]

Muhammad Haykal says, “For the management and disposal to belong to the Imam represents the ‘Asl (original position) in relation to the Qitaal (fighting) of the enemies, when he exists, and it is obligatory to obey him in accordance to the speech of Allah ta’ala:

يَـٰٓأَيُّهَا ٱلَّذِينَ ءَامَنُوٓا۟ أَطِيعُوا۟ ٱللَّهَ وَأَطِيعُوا۟ ٱلرَّسُولَ وَأُو۟لِى ٱلْأَمْرِ مِنكُمْ

“O believers! Obey Allah and obey the Messenger and those in authority among you.”[92]

…Based upon this understanding, the one entitled to dispose of the affairs of Al-Qitaal is only the Imam and consequently obedience to the Imam is obligatory in respect to the matters related to managing the matter or affairs of Al-Qitaal.”[93]

Case Study: The First Crusade