- Terrorism is not Jihad

- The Islamic Conquests

- Importance of Correct Military Structuring

- The Amir of Jihad

- Civilian Control of the Military

- The Emirate of Jihad encompasses more than just fighting

- The Caliph is the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces

- Will the Caliph lead the armies directly?

- Preventing Coup d’états

- Administrative Structure of the Military

- Flags of the Armed Forces

- Notes

Every state must have an army to protect its interests at home and abroad, and the Islamic State is no different in this regard. Although the word jihad has become a controversial term nowadays due to the west and its media equating it with terrorism, no one can dispute that fighting to make Allah’s word the highest i.e. that the systems and laws in the land are based on sharia is a major part of the Islamic religion, and two billion of the world’s population would not be Muslim today if it wasn’t for these conquests that took place over the centuries. The Prophet ﷺ said,

رَأْسُ الأَمْرِ الإِسْلاَمُ وَعَمُودُهُ الصَّلاَةُ وَذِرْوَةُ سَنَامِهِ الْجِهَادُ

“The head of the matter is Islam, and its pillar is the prayer, and its hump[1] is Jihad.”[2]

Allah (Most High) says,

ٱلَّذِينَ أُخْرِجُوا۟ مِن دِيَـٰرِهِم بِغَيْرِ حَقٍّ إِلَّآ أَن يَقُولُوا۟ رَبُّنَا ٱللَّهُ ۗ وَلَوْلَا دَفْعُ ٱللَّهِ ٱلنَّاسَ بَعْضَهُم بِبَعْضٍۢ لَّهُدِّمَتْ صَوَٰمِعُ وَبِيَعٌۭ وَصَلَوَٰتٌۭ وَمَسَـٰجِدُ يُذْكَرُ فِيهَا ٱسْمُ ٱللَّهِ كَثِيرًۭا ۗ وَلَيَنصُرَنَّ ٱللَّهُ مَن يَنصُرُهُۥٓ ۗ إِنَّ ٱللَّهَ لَقَوِىٌّ عَزِيزٌ

˹They are˺ those who have been expelled from their homes for no reason other than proclaiming: “Our Lord is Allah.” Had Allah not repelled ˹the aggression of˺ some people by means of others, destruction would have surely claimed monasteries, churches, synagogues, and mosques in which Allah’s Name is often mentioned. Allah will certainly help those who stand up for Him. Allah is truly All-Powerful, Almighty.[3]

In the first two centuries of Islamic history, the life of the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ – sīrah – was more commonly known as maghāzī (military expeditions). The earliest sīrah book we have is Kitab al-Maghāzī[4] by the Tabi’i scholar Musa ibn ‘Uqbah (d.758CE).

John Saunders says, “Once and once only, did the tide of nomadism flow vigorously out of Arabia. Bedouin raids on the towns and villages of Syria and Iraq had been going on since the dawn of history, and, occasionally an Arab tribe would set up a semi-civilized kingdom on the edge of the desert, as the Nabataeans did at Petra or the Palmyrenes at Tadmur, but conquests only occurred at the rise of Islam.”[5]

Fred Donner says, “In any case there can be no doubt that, from the very beginning, the Islamic state not only had a clearly identified sovereign (whatever he was called), but also seems to have had a clear concept of sovereignty which articulated the idea that the state should establish a properly righteous public order under the direction of the Believers, guided especially by the Qur’an, and that expansion of the state into new areas was a legitimate—indeed, an obligatory—endeavour. (However, it should be noted that this is not the same as demanding that everyone embrace the new faith.) Blankinship observes that the drive ‘to establish God’s rule in the earth’ through jihad, or active struggle, made the early Islamic state more ideological than any state that had existed before it, and has aptly called it the ‘jihad state’.”[6]

Terrorism is not Jihad

US President George W. Bush famously said after 9/11, “Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists.”[7] America and the other major world powers want free reign to plunder the resources of the earth, and will not hesitate in bombing, invading and massacring the inhabitants of resource-rich countries in order to achieve this. Anyone who dares to physically strive against their cruel campaigns is labelled a terrorist, unless the aims of these fighters happen to coincide with the interests of a particular world power. As the saying goes, “one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter.” U.S. President Ronald Reagan in reference to the Afghan Mujahideen fighting the Soviets said in 1983, “To watch the courageous Afghan freedom fighters battle modern arsenals with simple hand-held weapons is an inspiration to those who love freedom.”[8] Twenty years later and the Afghan freedom fighters became the first target of America’s global war on terror.

The Islamic Conquests

The takfiri groups have also contributed towards this maligning of jihad, by contradicting the clear commandments in the Qur’an and Sunnah related to what is permitted and not permitted in warfare. These strict rules of engagement especially with regards to non-combatants were enacted for over a millennium during the Islamic conquests. The Muslim armies did not commit genocides or wanton destruction of the peoples they conquered, because the objective of jihad is not to kill people or plunder their country’s resources. Jihad has a very clear objective which is to make Allah’s word the highest i.e. that justice is established by implementing the Islamic sharia in the lands it governs.

Montgomery Watt (d.2006) says, “Islamic ideology alone gave the Arabs that outward-looking attitude which enabled them to become sufficiently united to defeat the Byzantine and Persian empires. Many of them may have been concerned chiefly with booty for themselves. But men who were merely raiders out for booty could not have held together as the Arabs did.”[9]

While abuses, mistakes and collateral damage occurred during these battles, since these are human armies not armies of angels, on the whole “rule of law at the height of war” became a mantra of the Islamic conquests. If this had not been the case, then the conquered peoples would have rid themselves of the Muslim occupiers as soon as they were able to. In fact, the opposite occurred. Many of these ‘conquered’ peoples – especially outside the Middle East – embraced Islam and then spread Islam from their territories. The Muslim general Tariq bin Ziyad who conquered Spain in 711CE was not an Arab, he was a convert to Islam from a Berber tribe in what is now Algeria.

John Saunders compares the Arab and Mongol Conquests. He says, “In consequence the Mongols remained strangers in these lands, hated alien conquerors, an army of occupation, putting down no roots, and winning no loyalty.”[10] He then contrasts the Arab and Mongol conquests of Persia, “The contrast cannot be more strongly pointed than by considering the case of Persia, which was conquered both by the Arabs and the Mongols. The Arab conquest transformed the whole life and ethos of Iran, a clean break was made with the Sassanid and Zoroastrian past, the nation began its history afresh, its ancient language was submerged and when it later revived was choked with Arabic words which modern patriotism has scarcely managed wholly to expel. The Mongol conquest roared over Persia like a hurricane, yet when it had passed, the character of the nation had undergone little change. The Persians had accepted the Arab religion, but the Mongols accepted the Persian religion. Cultural continuity was maintained, despite enormous physical damage, and the Persian language was not only almost unaffected by Mongol but actually rose to be virtually the official language of the Mongol Empire.”[11]

Thomas Arnold, an orientalist and a Christian makes an observation of Islamic rule with regards its non-Muslim citizens (dhimmi): “But of any organised attempt to force the acceptance of Islam on the non-Muslim population, or of any systematic persecution intended to stamp out the Christian religion, we hear nothing.

Had the Caliphs chosen to adopt either course of action, they might have swept away Christianity as easily as Ferdinand and Isabella drove Islam out of Spain, or Louis XIV made Protestantism penal in France, or the Jews were kept out of England for 350 years.

The Eastern Churches in Asia were entirely cut off from communion with the rest of Christendom, throughout which no one would have been found to lift a finger on their behalf, as hereticalcommunions. So that the very survival of these churches to the present day is a strong proof of the generally tolerant attitude of the Muhammadan governments towards them.”[12]

Importance of Correct Military Structuring

Turning back to the discussion at hand, since the armed forces play such a major role in the Islamic state, their organisation and administration must be managed correctly. The military has its own culture and ethos, and is resistant to change. If not handled properly they can become a separate entity looking after the interests of themselves, rather than those of the state. In 1905, Field Marshal Sir Evelyn Wood told Richard Haldane, the Secretary of State for War, “If you organize the British army, you will ruin it.”[13]

If the military becomes independent this may lead to riots, civil wars and even coup d’états as were witnessed during the Abbasid Caliphate after the formation of a professional standing army of freed Turkish slaves (Ghilmans/Mamluks) by the caliph Al-Mu’tasim (r. 833-842). The rise of the Turkic army and their power struggles with the Abbasid Caliphs, led them to assassinate Al‐Mutawakkil (r. 847-861) and install his son Al-Muntasir (r. 861–862) as the caliph. The subsequent coup d’états, assassinations and civil strife in the new Abbasid capital of Samarra, are known as the Anarchy of Samarra (861-870) in which the removal and murder of five caliphs took place within just nine years.

Unfortunately, many of the militaries in Muslim countries today do not act in the interests of Islam and the state, because the top brass are simply bought off by the west. It’s no secret that the Pakistan military for example runs a huge number of commercial ventures and that its senior officers and generals have become extremely wealthy on the back of this.[14]

The Amir of Jihad

The title Amir ul-Jihad (أَمِير الجِهاد) which literally means the Leader of War, is a grammatical construction (إِضافَة Iḍāfah) mostly used to indicate possession. As a formal title it was not used in the time of the Prophet ﷺ or the Rightly Guided Caliphate. Only the title Amir was used without the appendage for the overall commanders of a battle. It was also used for the commanders of smaller expeditions (sariyya) since the word Amir is a general term for any leader of any function even if it’s over two people. The Messenger of Allah ﷺ said:

إِذَا خَرَجَ ثَلاَثَةٌ فِي سَفَرٍ فَلْيُؤَمِّرُوا أَحَدَهُمْ

“When three are on a journey, they should appoint one of them as their Amir.”[15]

The Prophet ﷺ would give the Amir of any expedition whether a small platoon (faṣīlah) or a large brigade (لِواء liwaʾ) a white flag called a liwaʾ which is the same word as a brigade. This flag is a special flag for the commander of an expedition (sariyya) or campaign, and by extension the commander in-chief of all the armed forces i.e. the caliph. Ryan Lynch says, “the Arabic term amīr is used to refer to a military commander regardless of his position in the chain of command.”[16]

The first liwaʾ to be raised in Islam was for Hamza ibn ‘Abd al-Muttalib in the month of Ramadan, seven months after the hijra of the Messenger of Allah ﷺ where he led an expedition of thirty men. The one who carried the liwaʾ was Abu Marthad Kinaz ibn al-Husayn al-Ghanawi.[17] Thirty men is the size of a modern-day platoon (فصيلة faṣīlah) headed by a Lieutenant (ملازم mulazim).

Abu Huraira narrates that the Messenger of Allah ﷺ sent out an expedition of ten men as spies, and their Amir was Asim bin Thabit al-Ansari.[18] Ten men is the size of a modern-day section (فرقة firqa) headed by a Corporal (عَرِيف ‘arif).

The Messenger of Allah ﷺ appointed Zaid ibn Haritha as the Amir of the Expedition to Mut’ah in charge of three thousand men and gave him a white liwaʾ.[19] Three thousand men is the size of a modern-day brigade (liwaʾ) headed by a one-star Brigadier-General (عَمِيد ‘amid).

The title Amir ul-Jihad which some modern structuralists have used within their models originates from Al-Mawardi’s wiliya – The Emirate of Jihad (الْإِمَارَةِ عَلَى الْجِهَادِ). Al-Mawardi describes this government function: “The Emirate of Jihad is particularly concerned with fighting the mushrikun and it is of two kinds:

1- That which is restricted to the affairs (siyasa) of the army and the management (tadbir) of war, in which case the conditions pertaining to special emirate (Amir Al-Khass) are applicable.

2- That in which all laws regarding the division of booty and the negotiation of the peace treaties are delegated to the amir, in which case the conditions pertaining to general amirate (Amir Al-‘Amm) are applicable. Of all the authorities of governance this is the most important with respect to its laws, and the most comprehensive with regard to its sections and departments.

This type of emirate, when special (khass), is subject to the same rulings as the general (‘amm)…”[20]

Al-Mawardi’s two types of Amir map to three modern day positions:

- Commander in-chief

- Chiefs of Staff

- Defence Secretary

The administrative systems (‘idara) can be adopted from any system, and we are not obliged to use the same army ranks, titles and formations as those used in the time of the Prophet ﷺ or later. Each time period will have its particular challenges, and the armed forces need to be structured in such a way to meet these. When the military is slow to reform, it can lead to disaster on the battlefield, as many battles of the first and second world wars show us.

Al-Mawardi’s first type of Amir is akin to an Executive Minister, who is a liaison between the caliph and the rest of the armed forces. We call this Executive Minister a Defence Secretary or Minister of Defence in modern times. This type of Amir can also map to the Joint Chiefs of Staff who are tasked with managing the day-to-day affairs of the army.

The second type of Amir Al-Mawardi describes is equivalent to a governor, who is the commander in-chief of his province, and by extension the caliph who is the commander in-chief over the entire state.

Civilian Control of the Military

Former French PM Georges Clemenceau said, “War is too serious a matter to entrust to military men.”[21] This is because military thinking focuses on achieving specific, measurable goals using force, while political thinking considers broader goals and uses a variety of tools, including military force, to achieve them. Military thinking emphasizes rationality, analytical skills, and feasibility, while political thinking involves critical examination, analysis of political concepts, and consideration of public interaction and the political dimension within a community.

Samuel Huntington (d.2008) says, “A minister of war need not have a detailed knowledge of military affairs, and soldiers often make poor ministers. The military viewpoint will inevitably, of course, interact with the political objective, and policy must take into account the means at its disposal. Clausewitz voices the military warning to the statesman to note carefully the limits of his military strength in formulating goals and commitments. But in the end, policy must predominate. Policy may indeed ‘take a wrong direction, and prefer to promote ambitious ends, private interests or the vanity of rulers,’ but that does not concern the military man. He must assume that policy is ‘the representative of all the interests of the whole community’ and obey it as such. In formulating the first theoretical rationale for the military profession, Clausewitz also contributed the first theoretical justification for civilian control.”[22]

The wider political goals that serve the long-term interests of Islam and the Muslims must always take precedent over short-term military objectives. This means that executive power and authority must always lie with the caliph who has effective leadership over the military. This cannot be a ceremonial position but must be a civilian-military role which is known in modern times as a Commander in-Chief. This position maps to the position held by the Prophet ﷺ and the Rightly Guided Caliphs.

Hitti says, “The army was the ummah, the whole nation, in action. Its amir or commander in chief was the caliph in al-Madinah, who delegated the authority to his lieutenants or generals. In the early stages the general who conquered a certain territory would also act as leader in prayer and as judge.”[23]

We can see this distinction between military and political thinking in the steps Abu Bakr took immediately after his election, where he defied the advice of the sahaba and sent out the army of Usama to Northern Arabia, at a time when Medina was being threatened by rebel tribes.

Abu Huraira described the events after the election of Abu Bakr as the first caliph in Islam. “The Messenger of Allah ﷺ directed Usamah ibn Zaid, along with seven hundred men, to Syria. When they arrived at Dhu Khushub the Prophet ﷺ died, the Arabs around Medina reneged on their Islam and the companions of the Messenger of Allah ﷺ gathered around him [Abu Bakr] and said, “Bring these back. Do you direct these against the Byzantines while the Arabs around Medina have reneged?” He [Abu Bakr] said, “By the One Whom there is no god but Him, even if dogs were dragging the wives of the Prophet ﷺ by their feet I would not return an army which the Messenger of Allah had sent out, nor undo a standard (لِواء liwaa’) which he had tied!”

He sent Usamah, and every tribe he would pass by which was wishing to renege would say (to themselves), “If these (the people of Madinah) did not have power, the like of these (the army) would not have come out from among them, so let us leave them alone until they meet the Byzantines.” They met them, defeated them, killed them and returned safely, so that they (the tribes) remained firm in Islam.”[24]

The policy of Abu Bakr here falls under the area of siyasa sharia (Islamic politics) which provides general principles and guidelines on how to execute Islamic rules. The fact that the majority of the sahaba disagreed with Abu Bakr shows it was not a definitive matter, as they would never collectively disobey the Prophet ﷺ in this way. They understood that the caliph has the authority to execute the rules of Islam, and now that the Prophet ﷺ had passed away it was Abu Bakr who now had this executive authority as the Commander-in-Chief. In fact, Abu Bakr and Umar were actually part of the Army of Usama, but Abu Bakr had to withdrew so he could run the state, and he needed Umar as his wazir in this great task. This shows that it was the prerogative power of the caliph to manage the army as he saw fit. There is no definitive correct answer when it comes to siyasa sharia and we see both sides of the sahaba were acting on an ijtihad and political opinion here. In hindsight one can say ‘I would have done it like this’ but in the heat of the moment you make the best decision you can. We should critically analyse some of the military and political decisions of the caliphs and generals throughout history, in order to learn from their successes and failures but keep in mind that in the heat of the moment they made the best decision they could. This is especially important when we discuss the rebellion against Uthman bin Affan and the civil war in the time of Ali ibn Abi Talib.

Lt. General Akram (d.1989) says, “The despatch of the Army of Usama was an act of faith displaying complete submission to the will of the departed Prophet, but as a manoeuvre of military and political strategy, it was anything but sound. This is also proven by the fact that all the Muslim leaders were opposed to the move-leaders who produced, in this and the following decades, some of the finest generals of history.”[25]

On his death bed Abu Bakr said, “Indeed, I do not grieve for anything from this world, except for three things which I did that I wish I had left aside, three that I left aside which I wish I had done, and three about which I wish I had asked Allah’s Messenger.”[26] He then describes some policies that he implemented that in hindsight he wished he had done differently. “I wish, on the day of Saqifat Bani Sa’idah, that I had thrown the matter upon the neck of one of the two men (meaning Umar and Abu Ubaydah) so that one of them would have become the Amir [of the Believers] and I would have been his wazir…

I also wish, when I sent Khalid b. al-Walid to fight the people of apostasy, that I had stayed at Dhu al- Qassah, so that if the Muslims had triumphed, they would have triumphed, but if they had been defeated, I would have been engaged or (provided) reinforcement.

Furthermore, I wish, when I sent Khalid b. al-Walid to Syria, that I had sent Umar b. al-Khattab to Iraq; thereby, I would have stretched forth both of my hands in Allah’s path. (He stretched forth both his hands.)”[27]

This level of scrutiny over one’s actions is the hallmark of a true sincere leader. Someone who is willing to admit their mistakes and rectify them if necessary. Umar ibn Al-Khattab famously said when he was caliph, “A woman is right and Umar is wrong.”[28] The level of accountability present in the Rightly Guided Caliphs is what sets them apart, and makes them an example to emulate for any leader today or in the future. The Prophet ﷺ said,

فَعَلَيْكُمْ بِسُنَّتِي وَسُنَّةِ الْخُلَفَاءِ الرَّاشِدِينَ الْمَهْدِيِّينَ عَضُّوا عَلَيْهَا بِالنَّوَاجِذِ

“I urge you to adhere to my sunnah and the sunnah of the Rightly-Guided Caliphs and cling stubbornly to it.”[29]

The Emirate of Jihad encompasses more than just fighting

Jihad links to the domestic and foreign policies of an Islamic State, and as such encompasses far more than just physical fighting. This is why Al-Mawardi said, “all laws regarding the division of booty and the negotiation of the peace treaties are delegated to the amir”. In other words, this Amir has powers related to the treasury and foreign policy, which is why in the time of the Rightly Guided Caliphs, this Amir was the military governor who had full powers as commander in-chief over the new lands he conquered. Abu Bakr appointed Khalid ibn Al-Walid as the commander of the second army[30] in the campaign to conquer Iraq. He then became the overall commander of all armies in Iraq[31], and the military governor of the newly conquered territories, until new civilian governors were appointed.

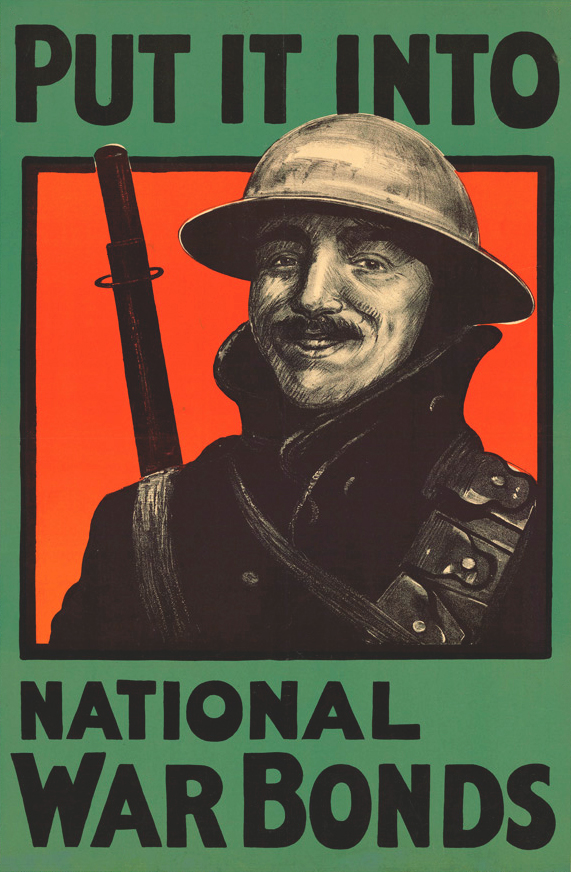

In a full-blown war, all aspects of the state and nation need to be mobilised for the war effort. We can see this in the first and second world wars in Britain, where factories were repurposed to make munitions, tanks and aircraft, and both men and women were conscripted in to the armed forces for service. War bonds were issued in WWI with a 5% interest rate, in order to raise money for the war, and ordinary citizens were encouraged to purchase these bonds out of their patriotic duty.

In order to achieve this mobilisation, there has to be someone in charge who has full powers over all aspects of the state and the armed forces. Winston Churchill, the wartime prime minister in WWII had this power, and additionally created a new title for himself called the “Minister of Defence” to reinforce his wartime powers. He said, “I, therefore, sought His Majesty’s permission to create and assume the style or title of Minister of Defence, because obviously the position of Prime Minister in war is inseparable from the general supervision of its conduct and the final responsibility for its result.”[32] He continues, “I may say, first of all, that there is nothing which I do or have done as Minister of Defence which I could not do as Prime Minister. As Prime Minister, I am able to deal easily and smoothly with the three Service Departments, without prejudice to the constitutional responsibilities of the Secretaries of State for War and Air and the First Lord of the Admiralty.”[33]

The Chancellor of the Exchequer and the Foreign Secretary in addition to the military chiefs of the three services (Army, Navy and Airforce), played major roles in the war cabinets of both world war governments. In 1942 Churchill replaced the Chancellor of the Exchequer’s position in the war cabinet with the Minister of Production and the Minister of Labour,[34] as these were essential functions to keep the war machine moving.

Although Churchill created the post of Minister of Defence, there was no Ministry of Defence (MOD) until after WWII. The three services of the armed forces namely the Admiralty, War Office and Air Ministry who controlled the Navy, Army and Airforce respectively, were separate departments until 1964 when they amalgamated into the MOD.[35]

The Caliph is the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces

In most Muslim countries today, the head of state is a mere figurehead in terms of their powers as the overall commander of the armed forces. They may hold titles such as Supreme Commander (القائِد الأَعْلَى) or even Commander-in-Chief (القائِد العامّ), but in reality they have no real effective power over the armed forces.

The Pakistan constitution states, “Without prejudice to the generality of the foregoing provision, the Supreme Command of the Armed Forces shall vest in the President.”[36]

The Egyptian constitution states, “The President of the Republic is the Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces.”[37]

The Turkish constitution states, “The Office of Commander-in-Chief is inseparable from the spiritual existence of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey and is represented by the President of the Republic.”[38]

This is why within the Muslim world so many western backed Coup d’états have occurred over the past decades, especially in the three countries mentioned above.

Taqiuddin Al-Nabhani says, “The army (جَيْش jaysh) must have a commander-in-chief (القائِد العامّ Al-Qa’id Al-‘Amm), who is appointed by the Head of State (رئيس الدولة Ra’is Al-Dowlah) as a deputy to him. This is because the commander in chief is the head of the entire army and armed forces (القُوّات المُسَلَّحَة Al-Quwwat Al-Musallaha). Likewise, every division (فِرْقَة firqa) must have a commander (قائِد Qa’id), and every brigade (لِواء liwa’) a commander and every battalion (كتيبة katība) a commander. All of them are appointed by the head of state, whereas the remaining officers are appointed by the commander-in-chief.”[39]

Al-Nabhani doesn’t use the title Commander-in-Chief for the Head of State, but rather uses it for the head of the armed forces. Abdul-Qadeem Zallum referred to the same position with the title Amir ul-Jihad. In most countries today, the Chief of Staff is the title used for the effective head of the armed forces. Prior to 1972, the head of the Pakistan army had the title Commander-in-Chief. After this time it was renamed to the Chief of Army Staff (COAS).

As with the other posts within the Islamic ruling system, we need to focus on the concept and hukm (rule) as opposed to the technical (istilahiyya) term. Al-Nabhani mentions that the head of state appoints all the generals and is the effective head of the armed forces. This is the important point here regardless of what title is used to describe this position.

The closest model we have nowadays, in relation to effective control of the armed forces which was practised by the Prophet ﷺ and the Rightly Guided Caliphs, is that of America and the role of the President as the Commander-in-Chief. This is not a ceremonial position but rather a civilian-military role where the US President appoints all the generals, chiefs of staff and campaign commanders. In terms of the chain of command this can go through the Defence Secretary as a deputy command-in-chief, but the President can also issue orders directly to the commanders in the field.

The US President also has the power to lead the wars directly and formulate military planning and strategy as George Washington, James Madison and Abraham Lincoln did when they were in office. This is similar to what the Prophet ﷺ and some of the caliphs undertook when they directly led the battles, trained the military or devised battle plans and strategy. Although this is an exception to the rule, and even during the time of the Prophet ﷺ, once the sahaba had been trained in military leadership, they led most of the later battles of the Medinan period.

An important point to note nowadays is that the armed forces have undergone a dramatic transformation, and military expertise is a full-time dedicated role by professional officers. The caliph would have been an army commander before assuming office as the Rightly Guided Caliphs were, but once in office his focus is on political affairs and he needs to delegate out the actual command, training and military planning to the chiefs of staff. “‘I am not acquainted with the military profession,’ George Mason proclaimed at the Virginia convention and, except for Hamilton, Pinckney, and a few others, he spoke for all the Framers [of the US Constitution]. They knew neither military profession nor separate military skills. Military officership was the attribute of any man of affairs. Many members of the Federal Convention had held military rank during the Revolution; Washington was only the most obvious of the soldier-statesmen. They combined in their own persons military and political talents much as the samurai founders of modem Japan also combined them a hundred years later.”[40]

Will the Caliph lead the armies directly?

The Prophet Muhammad ﷺ in his role as a ruler-prophet and head of state in Medina led many of the battles himself since he was the Commander-in-Chief. A battle or expedition that he ﷺ led directly is referred to in the Islamic history books as a ghazwa. Those expeditions where he appointed a sahabi to command are referred to as a sariyya.

We can see from the data that the number of expeditions led directly by the Prophet ﷺ decreased over time as the sahaba took a more leading role after their training at the hands of the Messenger ﷺ.

The Prophet ﷺ appointed a total of 43 different sahaba as commanders so they all gained experience in this role. After his ﷺ death these commanders played a vital role in the Islamic conquests such as Khalid ibn Al-Walid, Amr ibn al-Aas and Abu Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah.

Three of the Rightly Guided Caliphs were appointed as military commanders namely, Abu Bakr, Umar and Ali. This experience was important for their future roles as Commanders-in-chief of their respective armies.

We can see a practical example at the Battle of Badr of how the Messenger of Allah ﷺ managed the military training of the sahaba. He ﷺ asked them:

كَيْفَ تُقَاتِلُونَ الْقَوْمَ إِذَا لَقِيتُمُوهُمْ

“How will you fight the people [enemy] when you meet them?”

So Asim bin Thabit stood up and said:

يَا رَسُولَ اللهِ إِذَا كَانَ الْقَوْمُ مِنَّا حَيْثُ يَنَالُهُمُ النَّبْلُ، كَانَتِ الْمُرَامَاةُ بِالنَّبْلِ، فَإِذَا اقْتَرَبُوا حَتَّى يَنَالَنَا وَإِيَّاهُمُ الْحِجَارَةُ، كَانَتِ الْمُرَاضَخَةُ بِالْحِجَارَةِ، فَأَخَذَ ثَلَاثَةَ أَحْجَارٍ فِي يَدَهِ وحَجَرَيْنِ فِي حِزْمَتِهِ، فَإِذَا اقْتَرَبُوا حَتَّى يَنَالَنَا وَإِيَّاهُمُ الرَّمَّاحُ، كَانَتِ الْمُدَاعَسَةُ بِالرِّمَاحِ، فَإِذَا انْقَضَتِ الرِّمَاحُ، كَانَتِ الْجِلَادُ بِالسُّيُوفِ

“O Messenger of Allah, when the people [enemy] are where the arrows will reach them, then the shooting will be with arrows. But when they come close until the stones reach us and them, then the fighting will be with stones. So he took three stones in his hand and two stones in his bundle. When they come close until the spears reach us and them, then the fighting will be with spears, and when the spears are destroyed, the fighting will be with swords.”

Then the Messenger of Allah ﷺ said,

بِهَذَا أُنْزِلَتِ الْحَرْبُ، مَنْ قَاتَلَ فلْيُقَاتِلْ قِتَالَ عَاصِمٍ

“With this war was revealed. Whoever fights, let him fight as Asim fights.”[41]

Being the Commander-in-Chief, doesn’t mean the caliph has to lead the armies directly, or even get involved in the day-to-day military training and planning activities, although he has the authority to do this. Once the Islamic state expanded to an ‘empire’ encompassing lands spanning multiple continents, it was not feasible or even wise for the caliph to perform this task.

It is related that ‘Aishah said, “My father went out with his sword unsheathed; he was mounted on his riding animal, and he was heading towards the valley of Dhil-Qissah ‘Ali ibn Abi Talib came, took hold of the reins of Abu Bakr’s riding animal, and said, “Where are you going, O Caliph of the Messenger of Allah?” The question was rhetorical, for ‘Ali knew very well that Abu Bakr planned to lead his army into battle. “I will say to you what the Messenger of Allah ﷺ said on the Day of Uhud,” ‘Ali went on. By this statement, ‘Ali was referring to what had happened on the Day of Uhud: When Abu Bakr wanted to engage in a duel-to-the-death with his son ‘Abdur-Rahman (who was still a disbeliever), the Prophet ordered him to draw back his sword and to return to his place. ‘Ali went on to say, “Draw back your sword and do not bring upon us the tragedy of your death. For by Allah, if we become bereaved of you, (the nation of) Islam will not have an organized system of rule (rather, due to the apostate problem, chaos will break out).” Abu Bakr acquiesced to ‘Ali’s demand and returned to Al-Medina.”[42]

Samuel Huntington describes the US situation: “The intention and the expectation of the Framers and of the people was that the President could, if he so desired, assume personal command in the field. Early presidents did not hesitate to do this. Washington personally commanded the militia called out to suppress the Whiskey Rebellion. James Madison took a direct hand in organizing the ineffectual defense of Washington in 1814. During the Mexican War, President Polk, although he did not command the army in the field, nonetheless personally formulated the military strategy of the war and participated in a wide range of exclusively military matters. The last instance of a President directly exercising military functions was Lincoln’s participation in the direction of the Union armies in the spring of 1862. The President personally determined the plan of operations, and, through his War Orders, directed the movement of troop units. It was not until Grant took over in Virginia that presidential participation in military affairs came to an end. No subsequent President essayed the direction of military operations, although Theodore Roosevelt in World War I argued conversely that his previous experience as Commander in Chief proved his competence to command a division in France.”[43]

Nowadays, due to the existence of professional standing armies, and the complexity of executive rule, the caliph will inevitably take a more back-seat role in terms of hands-on military, even though he would have been a military commander before coming to office. He does however need to keep a hands-on role in terms of the chain of command, and the appointment and dismissal of the generals and campaign commanders. This ensures the loyalty of the top brass to the caliph and not to the Chief of Staff, or any other body or individual minister.

Samuel Huntington describes the Commander-in-Chief role of the US President vis-à-vis the military command: “This unified hierarchy began to break up as the military function became professionalized. The President was no longer qualified to exercise military command, and even if he were qualified by previous training, he could not devote time to this function without abandoning his political responsibilities. The political functions of the Presidency became incompatible with the military functions of the Commander in Chief. Nor were the civilian politicians appointed Secretaries of War and the Navy competent to exercise military command. On the other hand, the emergence of the military profession produced officers whose experience had been exclusively military, who were quite different types from the politician secretaries, and who were technically qualified to command. The constitutional presumption that the President exercised command still remained, however, and complicated the relations among President, secretary, and military chief. [44]

Winston Churchill in WWII outlined his policy with regards to the supervision of the military. “It is my practice to leave the Chiefs of Staff alone to do their own work, subject to my general supervision, suggestion and guidance.” He continues, “Each of the three Chiefs of Staff has, it must be remembered, the professional executive control of the Service he represents.”[45]

This policy will be adopted by the head of an Islamic state who keeps just enough control to prevent the independence of the military, and ensure they work to achieve the interests of Islam alone, since the sharia is sovereign, and not any individual including the caliph himself.

Preventing Coup d’états

There are three ways the caliph as Commander-in-Chief keeps full effective control of the armed forces.

- The bay’ah contract

- No obedience in sin

- Appointment and dismissal of the general staff

1- The bay’ah contract

The bay’ah or pledge of allegiance, is a ruling contract which governs the relationship between Muslims and the Islamic state. For those Muslims living under the authority of the state, the bay’ah is their citizenship contract with its ruler – the caliph.

This oath and pledge contains explicit words of loyalty and obedience to the head of state.

Ubada ibn Al-Samit said:

بَايَعْنَا رَسُولَ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم عَلَى السَّمْعِ وَالطَّاعَةِ فِي الْمَنْشَطِ وَالْمَكْرَهِ. وَأَنْ لاَ نُنَازِعَ الأَمْرَ أَهْلَهُ، وَأَنْ نَقُومَ ـ أَوْ نَقُولَ ـ بِالْحَقِّ حَيْثُمَا كُنَّا لاَ نَخَافُ فِي اللَّهِ لَوْمَةَ لاَئِمٍ

“We gave the bayah to Allah’s Messenger that we would listen and obey him both at the time when we were active and at the time when we were tired, and that we would not fight against the ruler or disobey him, and would stand firm for the truth or say the truth wherever we might be, and in the Way of Allah we would not be afraid of the blame of the blamers.”[46]

Every citizen, including every soldier no matter his/her rank are bound first and foremost by the bay’ah.

2- No obedience in sin

Following on from this, the implementation of any law relies on the consent of the people to obey the law. If the government doesn’t have the legitimacy to rule (authority) from the strongest faction in the society, then you will inevitably end up with a police state – something Islam forbids – and which will eventually crumble and disappear as we have witnessed during and after the Arab spring.

The authority in an Islamic state is derived from people’s belief in Islam and its culture. If the ideology of Islam is strong within people, then inevitably the authority will also be strong. What makes the Rightly Guided Caliphate such a strong era where the Roman and Persian empires who had ruled for centuries crumbled within just a few decades after Islam’s emergence, was not down to the caliph alone. Rather it was down to the strength of the wazirs, commanders, advisors and governors who were all senior sahaba, and the strongest generation in terms of Islamic thought and practice. The Prophet ﷺ said, خَيْرُ النَّاسِ قَرْنِي “The best people are those of my generation.”[47]

The military structure is built upon obedience to the officers in command, and without this the entire apparatus would fall apart. Having said this, there are limits to this obedience and any moves by senior officers to undermine the caliph and his government, and commit treason through an illegitimate coup d’etat must be disobeyed. The Prophet ﷺ said,

لاَ طَاعَةَ فِي مَعْصِيَةٍ، إِنَّمَا الطَّاعَةُ فِي الْمَعْرُوفِ

“There is no obedience to anyone if it is disobedience to Allah. Verily, obedience is only in good conduct.”[48]

The Prophet ﷺ sent a sariyya (expedition) under the command of a man from the Ansar and ordered the soldiers to obey him. He (the commander) became angry and said “Didn’t the Prophet order you to obey me!” They replied, “Yes.” He said, “Collect fire-wood for me.” So they collected it. He said, “Make a fire.” When they made it, he said, “Enter it (the fire).” So they intended to do that and started holding each other and saying, “We run towards (i.e. take refuge with) the Prophet from the fire.” They kept on saying that till the fire was extinguished and the anger of the commander abated. When that news reached the Prophet ﷺ he said, “If they had entered it (the fire), they would not have come out of it till the Day of Resurrection. Obedience is [only] required when he enjoins what is good.”[49]

The soldiers on this sariyya obeyed the officer in command up until he ordered them with a clear-cut definitive sin i.e. suicide.

3- Appointment and dismissal of the general staff

The caliph is the Commander-in-Chief and as such appoints all the generals of all the services – Army, Navy and Airforce, and the Chiefs of Staff who head each of their respective services.

The lower ranks (colonel and below) are approved by the promotion boards, overseen by the general staff. This is the same as the US system with one major difference. In the US system all appointments by the President to the general staff must be approved by the Senate Armed Forces Committee. In the Islamic State there is no such requirement in principle, but since shura is a fundamental principle of the Islamic system, then these appointments will be scrutinised by the upper house – Dar Al-‘Adl – which institutionalises part of the Mazalim (judicial redress) principle outlined by Al-Mawardi. This will be discussed later.

Every single Amir of an expedition no matter how large or small was appointed by the Prophet ﷺ. The Rightly Guided Caliphs followed this method by appointing the heads of the armies and even some of the deputies. The lower ranks would be appointed by the Amir of the expedition or campaign.

The Messenger of Allah ﷺ appointed Zaid ibn Haritha as the Amir of the Expedition to Mut’ah in charge of three thousand men and gave him a white liwaʾ.[50] Three thousand men is the size of a modern-day brigade (liwaʾ) headed by a one-star Brigadier-General (عَمِيد ‘amid). In this campaign he ﷺ didn’t just appoint Zaid but also appointed the deputy commanders who would take over if Zaid was killed. He ﷺ said, “The Amir of the people is Zayd bin Haritha. If he is killed, then Ja’far ibn Abi Talib. If he is killed, then Abdullah ibn Rawahah. If he is killed, then let the Muslims choose a man from among themselves and make him their Amir.”[51]

Umar ibn al-Khattab, when he was caliph appointed Amr ibn Al-‘Aas as the Amir (commanding-general) of the Egyptian campaign. Umar wrote a letter to Amr:

“I am very surprised at how long it is taking to conquer Egypt, as you have been fighting for the last two years, unless it is because of some sins that you have committed, or you have started to love this world as your enemy does. Allah, may He be blessed and exalted, only grants victory to people who are sincere. I am sending to you four individuals, and I have told you that each one of them is equivalent to one thousand men as far as I know, unless something has changed them…”[52] These four individuals were well-experienced commanders, each in charge of a battalion (كتيبة katība) of 1000 men. These commanders were Al-Zubayr ibn al-‘Awwam, Al-Miqdad ibn al-Aswad, ‘Ubadah ibn as-Samit and Maslamah ibn Mukhallad.

In famous incident during the caliphate of Umar, he dismissed Khalid ibn al-Walid, the sword of Allah as the Amir of the army in Syria and appointed Abu Ubaydah ibn Al-Jarrah in his place. Even though Khalid was more qualified military than Abu Ubaydah, Umar’s decision was based on wider political thinking and the ramifications of keeping Khalid in place. This links back to the discussion on civilian control or political control of the military. Military decisions need to always be subservient to the wider political goals of the state. Umar was afraid that the people were too attached to Khalid and believed that victory was connected to Khalid’s blessing and military expertise, and that they would put their trust in that rather than Allah.[53]

In his letter explaining the dismissal of Khalid, Umar wrote, “I am not dismissing Khalid out of anger or betrayal, rather the people have become confused because of him, and I want them to know that Allah is the One who does what He wills.”[54]

The chain of command in an Islamic State is therefore from the caliph directly to the combatant commanders on the ground. Similar to America, the Chiefs of Staff are not in the chain of command, and are simply advisors to the caliph charged with preparing the armed forces to fight to the best of their ability.

These are three ways that the Islamic state protects itself against the encroachment of the military into politics and civilian affairs. If this model was in place, then Mohamed Morsi (d.2019) the former President of Egypt wouldn’t have been removed so easily by General Sisi who was his Minister of Defense and Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces.[55] In this position, Sisi had effective control over the military, with Morsi’s role as Supreme Commander being a mere ceremonial position.[56]

Administrative Structure of the Military

Al-Mawardi lists ten responsibilities[57] for the Amir of the army. These responsibilities in modern times fall under the remit of the defence department and the Chiefs of Staff who are tasked with creating a highly proficient and effective Islamic military, that is capable of assisting the caliph in protecting Islamic interests both at home and abroad.

| 1 | Protecting the army from attack |

| 2 | Choosing the best location for the army encampments |

| 3 | Preparing provisions for the army |

| 4 | Knowledge of the enemy, their movements and tactics |

| 5 | Organising the army for battle |

| 6 | Motivating the army to fight by remembering Allah’s help |

| 7 | Motivating the army to fight by remembering the immense reward of jihad |

| 8 | Consulting the military experts for advice (shura) |

| 9 | Ensuring that the army adheres to the sharia rules of engagement |

| 10 | The army must concentrate on military matters and not involve itself in trade and agriculture |

The duties listed above cover a wide-range of areas including logistics, intelligence and educational programmes (tarbiya). These areas require the input and assistance of many other parts of the state such as the education department and treasury. This is why it’s important that the caliph is the effective head of the army, so as head of the executive branch he can order all his department heads to assist the military when and if required.

It’s important to reiterate that administration (إِدارَة idara) can be adopted from any system. Every time period has its own specific realities and problems, and so the military must be structured in such a way as to meet these challenges. If that means copying the military structure of America, Russia or China then so be it. The Islamic state must be a dynamic state ready to do whatever is necessary within the limits of the sharia, to achieve rapid development and progress in all spheres of life. This can only be achieved with a clear understanding of what the sharia allows, and does not allow, when it comes to imitation of the non-Islamic systems of governance.

Sheikh Ibn al-Uthaymin (d.2001) says, “If it is said, ‘Imitating the disbelievers,’ means that we should not use anything of their crafts. No one would say that. During the time of the Prophet ﷺ and after him, people used to wear clothing made by the disbelievers and use utensils made by them.

Imitating the disbelievers means imitating their clothing, their adornments, and their special customs. It does not mean that we should not ride what they ride, or that we should not wear what they wear. However, if they ride in a specific way that is unique to them, then we should not ride in this way. If they tailor their clothes to a specific way that is unique to them, then we should not tailor them in this way, even if we ride in a car like the one they ride in, and we tailor from the same type of fabric that they tailor from.”[58]

He also mentions, “Imitating the disbelievers means that a person adopts their attire in dress, speech, or the like, such that when someone sees him, he says: This is one of the disbelievers.” As for what Muslims and disbelievers share, this is not imitation. For example, now men wear trousers. We do not say this is imitation, because it has become a habit for everyone.”[59]

Brigadier-General Dr. Muhammad Damir Witr lists eight military administrations that were found in the time of the Prophet ﷺ.

| 1 | planning and organisation |

| 2 | Shura (consultation) |

| 3 | directing the morale |

| 4 | information gathering |

| 5 | operations |

| 6 | training and equipping |

| 7 | provisions, supplies and booties |

| 8 | medical services |

He then says: “These administrations used to undertake their tasks according to the obligatory military requirements, and they did not have specific structures like we see today just as they were not (completely) separate from each other or from the field army in respect to its actions and elements. That is because it was possible for a fighter to also be charged with reconnaissance and with another task at the same time. All of these administrations were headed by a single head who assumed their administration and the supervision over them. He was the Commander-in-Chief (Qa’id Al-‘Amm).

Also, these administrations were not concentrated in a particular or specific location, but were rather included within the army and moved with it and were located or concentrated along with it. For that reason, the teeth of the army were stronger than its tail and its fighting elements were greater in number than its administrative elements”[60]

Muhammad Haykal comments on this, “From all of this, it becomes clear that the different organisational elements upon which the matters or affairs of the army and its conditions revolve, fall under the area or scope of the Mubaahaat (permissible matters). That is as long as they do not contravene the Ahkaam Ash-Shar’iyah, and that applies whether those matters are related to the centres where the army is established and its distribution upon the fronts and different regions, or related to its military formations, the clothing that it individuals wear or its organisation of military ranks, in addition to the many other organisational aspects related to the army…”[61]

Flags of the Armed Forces

Ibn Khaldun says, “Flags have been the insignia of war since the creation of the world. The nations have always displayed them on battlefields and during raids. This was also the case in the time of the Prophet and that of the caliphs who succeeded him.”[62]

If we look to the hadith then we find two types of flags used by the leader and commanders of the Islamic army. They are the liwaa’ (اللِواء) and the rayah (الرايَة) which are translated as flags or banners. The rayah is black and the liwaa’ is white.

أخرج الترمذي وابن ماجه عَنْ ابْنِ عَبَّاسٍ قَالَ: كَانَتْ رَايَةُ رَسُولِ اللَّهِ صَلَّى اللَّهُ عَلَيْهِ وَسَلَّمَ سَوْدَاءَ، وَلِوَاؤُهُ أَبْيَضَ

At-Tirmidhi and Ibn Majah have narrated on authority of Ibn Abbas who said: “The rayah of Prophet Mohammad ﷺ was black, and his liwaa’ was white.”[63]

Al-Sarakhsi says, “Black was preferred for rayahs because it is a sign for those fighting, and every group fights under their rayah, and if they scatter during the fighting they can return to their rayah, and black is clearer and more noticeable in daylight than other colors, especially in dust. That is why it was preferred.”[75]

Al-Sarakhsi continues, “From a sharia perspective, there is no objection to making the rayahs white, yellow, or red. However, white is chosen for the liwaa‘ because the Prophet (saw) said: “The most beloved garment to Allah Almighty is white, so let your living wear it and shroud your dead in it.” Each army should have only one liwaa‘, and they refer to it when they need to present their affairs to the sultan. Therefore, white is chosen to distinguish it from the black rayahs used by the commanders.”[76]

The liwaa’ is a special flag used as a sign for the commander of a particular mission or expedition (sariyya), and the leader of the armed forces as a whole (commander in-chief). In origin it is a plain white flag, but any Islamic emblem such as the shahada (declaration of faith)[64] can be added to it.

Al-Hafiz Ibn Hajar says that the liwaa’,

وهو العلم الذي في الحرب يعرف به موضع صاحب الجيش، وقد يحمله أمير الجيش، وقد يدفعه لمقدم العسكر

“it is the sign (‘alam) by which the position of the commander of the army is known in war. It may be carried by the Amir of the army, or he may give it to the leader of the army.”[65]

Al-Sarakhsi (d.1090CE) says,

ثم اللواء اسم لما يكون للسلطان، والراية اسم لما يكون لكل قائد تجتمع جماعة تحت رايته

“Then the liwaa‘ is the name given to what belongs to the sultan, and the rayah is the name given to what belongs to each commander (qa’id) under whose rayah a group gathers.”[74]

The first liwaa’ to be raised in Islam was for Hamza ibn ‘Abd al-Muttalib in the month of Ramadan, seven months after the hijra of the Messenger of Allah ﷺ where he led a sariyya of 30 men. The one who carried the liwaa’ was Abu Marthad Kinaz ibn al-Husayn al-Ghanawi.[66]

The rayah is a more general flag used by the entire armed forces including the various divisions, brigades and battalions. It is a plain black flag, but similar to the liwaa’, any Islamic emblem such as the shahada can be added to it. It is a sign of the sub-commanders in a battle.

The first time the rayah was used, was at the Ghazwa (campaign) of Khaybar in the seventh year of the hijra. The Muslim army marched against Banu Nadir who were located outside Medina at a town called Khaybar. The army camped outside their fortresses and the Messenger of Allah ﷺ preached to the people and distributed rayahs among them. There were no rayahs before the day of Khaybar, only liwaa’s. The rayah of the Prophet ﷺ was black from the cloak of Aisha, called Al-Uqab, and his liwaa’ was white, which he gave to Ali ibn Abi Talib. One rayah went to Al-Hubab ibn Al-Mundhir, and one rayah went to Sa’d ibn ‘Ubadah.[67]

Al-Hubab and Sa’d were therefore sub-commanders, with Ali being the Prophet’s ﷺ deputy.

Therefore, the liwaa’ and the rayah were assigned to the Amir and sub-commanders of the battles. In modern armed forces these commanders are actually known as “flag officers”. A flag officer is a commissioned officer in a nation’s armed forces senior enough to be entitled to fly a flag to mark the position from which that officer exercises command.[68]

Each brigade and battalion can also fly their own flag to distinguish their position on the battlefield.

إِنَّ النَّبِيَّ صَلَّى اللهُ عَلَيْهِ وَسَلَّمَ عَقَدَ رَايَاتِ الْأَنْصَارِ فَجَعَلَهُنَّ صُفَرًا

“The Prophet ﷺ knotted the flags (rayaat) of al-Ansar and made them yellow.”[69]

وَإِنَّ النَّبِيَّ صَلَّى اللهُ عَلَيْهِ وَسَلَّمَ عَقَدَ رَايَةَ بَنِي سُلَيْمٍ حَمْرَاءَ

“… And the Prophet ﷺ knotted the flag (rayah) of Bani Suleim red”.[70]

Qutba bin Amer carried the rayah of Banu Salamah in the Conquest of Mecca.[71]

Salim, the mawla of Abu Hudhayfah, carried the rayah of the Muhajireen at the Battle of Yamama under the caliphate of Abu Bakr, and fought until he was martyred.[72]

Warfare has changed considerably in modern times and armies no longer have flag bearers during the height of battle. Flags are now relegated to patches and insignia on the uniform, with flags only flown to identify an area as being under the command of a particular force once the area is secured.

Muhammad [al-Shaybani] said: “Every group should adopt a slogan (شِعار) when they go out on military expeditions, so that if a man gets lost from his companions, he can call out their slogan. Likewise, the people of each rayah should have a known slogan, so that if a man gets lost from his rayah, he can call out his slogan and thus be able to return to them. This is not a religious obligation, so even if they do not do it, they are not sinning. However, it is better, more effective in warfare, and closer to conforming with what has been narrated in the traditions.”[77]

Reviving the Prophet’s ﷺ flags and banners is important though, because it helps in reinforcing the Islamic values of the soldiers, and reminding them that their mission is for Allah alone.

We can see an example of this during Egypt’s 1973 war to retake the Sinai Peninsula from Israel named Operation Badr after the Battle of Badr. On the 6th October 1973 (10th Ramadan), the Egyptian army launched a surprise attack against the Israeli forces occupying the east bank of the Suez Canal. This lightening attack destroyed the ‘invincible’ Bar-Lev Line, a chain of Israeli fortifications along the east bank of the canal. “A day or two after the crossing of the canal, the army information services had a leaflet printed which was distributed to all serving soldiers. This was couched in the most flowery language of piety: ‘In the name of Allah, the merciful, the compassionate: the Prophet is with us in the battle. O Soldiers of Allah . . . etc. etc.’ It went on to say that ‘one of the good men’ had had a dream in which he saw the Prophet Muhammad dressed in white, taking with him the Sheikh of el-Azhar, pointing his hand and saying ‘come with me to Sinai’. Some of the ‘good men’ were reported to have seen the Prophet walking among the soldiers with a benign smile on his face and a light all around him. So it went on, ending up: ‘O soldiers of Allah, it is clear that Allah is with you.’”[73]

Notes

[1] Abdul Mohsen Al-Abbad (b.1935) explains the meaning of hump (سَنام): “Jihad is called the pinnacle of the hump of Islam because in it is the elevation of Islam, its appearance and strength of the Muslims, and their superiority over the disbelievers and their victory over them.” [Explanation of Nawawi’s Forty Hadiths, https://shamela.ws/book/36944/723 ]

[2] Jami’ at-Tirmidhi 2616, https://sunnah.com/tirmidhi:2616

[3] Holy Qur’an, Surah Al-Hajj, ayah 40

[4] Musa ibn ‘Uqbah, ‘The Maghāzī of Sayyidunā Muhammad ﷺ,’ Imam Ghazali Publishing, 2004, https://imamghazali.co.uk/products/maghazi-ebook

[5] Fred M. Donner, ‘The Expansion of the Early Islamic State,’ 2008, Routledge, p.39; John J Saunders, ‘The Nomad as Empire Builder: A Comparison Of The Arab And Mongol Conquests’

[6] Fred Donner, ‘The Articulation of Early Islamic State Structures,’ Routledge, 2012, p.xviii

[7] George W. Bush, ‘Address to a Joint Session of Congress and the American People,’ 20 September 2001, https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2001/09/20010920-8.html

[8] U.S. President Ronald Reagan, ‘Message on the Observance of Afghanistan Day,’ March 21, 1983, https://web.archive.org/web/20101116103312/http://www.reagan.utexas.edu/archives/speeches/1983/32183e.htm

[9] W. Montgomery Watt, “Economic and Social Aspects of the Origin of Islam,” Islamic Quarterly, 1, 1954.

[10] Fred M. Donner, ‘The Expansion of the Early Islamic State,’ 2008, Routledge, p.51; John J Saunders, ‘The Nomad as Empire Builder: A Comparison Of The Arab And Mongol Conquests’

[11] Fred M. Donner, ‘The Expansion of the Early Islamic State,’ 2008, Routledge, p.60; John J Saunders, ‘The Nomad as Empire Builder: A Comparison Of The Arab And Mongol Conquests’

[12] Thomas W. Arnold, ‘The Preaching of Islam,’ Second Edition, Kitab Bhavan Publishers, New Delhi, p.72

[13] Stephen E. Koss, Lord Haldane, Scapegoat for Liberalism (New York: Columbia University Press, 1969), 47.

[14] https://www.dawn.com/news/1272211

[15] Sunan Abi Dawud 2608, https://sunnah.com/abudawud:2608

[16] Ryan J. Lynch, ‘Arab Conquests and Early Islamic Historiography: The Futuh al-Buldan of al-Baladhuri,’ I.B. Tauris, 2020 p.147

[17] Ibn Sa’d, Tabaqat, https://shamela.ws/book/1686/392

[18] Sahih Al-Bukhari 3045, https://sunnah.com/bukhari:3045

[19] Ibn Sa’d, Tabaqat, https://shamela.ws/book/1686/487#p1

[20] Al-Mawardi, Op.cit., p.57; https://shamela.ws/book/22881/64

[21] Georges Clemenceau. Former Prime Minister of France, https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/acref/9780191843730.001.0001/q-oro-ed5-00003062

[22] Samuel Huntington, ‘The soldier and the state: The theory and politics of civil-military relations,’ p.58

[23] Philip K. Hitti, ‘History of the Arabs,’ London, 10th edition, 1970, p.173

[24] Jalal ad-Din as-Suyuti, ‘The history of the Khalifahs who took the right way’, translation of Tareekh ul-Khulufaa, Ta Ha Publishers, p.60; https://shamela.ws/book/11997/63

[25] Lt. General Akram, ‘Khalid ibn Al-Walid: The Sword of Allah’, Chapter 11: The Gathering Storm

[26] al-Tabari, ‘The History of Al-Tabari’, translation of Ta’rikh al-rusul wa’l-muluk, State University of New York Press, Volume XI, p.149

[27] Ibid

[28] Muhammad As-Sallaabi, ‘Umar ibn Al-Khattab, his life and times,’ vol.1, p.215

[29] Sunan Ibn Majah 42, https://sunnah.com/ibnmajah:42

[30] Dr Ali Muhammad As-Sallabi, ‘The Biography of Abu Bakr As-Siddiq’, Dar us-Salam Publishers, p.555

[31] al-Tabari, Op.cit., Vol. XI, p.5

[32] Hansard, War Situation, Volume 378: debated on Tuesday 24 February 1942, https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1942-02-24/debates/02dd8f21-e6ac-46fa-a5ee-bcf707b9bfee/WarSituation

[33] Ibid

[34] Ibid

[35] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a799eb0e5274a684690ae08/history_of_mod.pdf

[36] https://www.pakistani.org/pakistan/constitution/part12.ch2.html

[37] https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Egypt_2019?lang=ar

[38] https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Turkey_2017

[39] Taqiuddin Al-Nabhani, Nizam ul-Hukm Fil-Islam, 1st Edition, 1951, p.54

[40] Samuel Huntington, ‘The soldier and the state: The theory and politics of civil-military relations,’ p.165

[41] Al-Tabarani, Al-Mu’jam al-Kabir 4513 https://shamela.ws/book/1733/5457

[42] Al-Bidaayah Wan-Nihaayah (2/319) quoted in Al-Sallabi’s Biography of Abu Bakr Siddiq, p.380

[43] Samuel Huntington, ‘The soldier and the state: The theory and politics of civil-military relations,’ p.185

[44] Ibid

[45] Hansard, War Situation, Volume 378: debated on Tuesday 24 February 1942, https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1942-02-24/debates/02dd8f21-e6ac-46fa-a5ee-bcf707b9bfee/WarSituation

[46] Sahih al-Bukhari 7199, 7200, https://sunnah.com/bukhari/93/60

[47] Sahih al-Bukhari 6429, https://sunnah.com/bukhari:6429

[48] Muttafaqun Alayhi (agreed upon). Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī 7257 https://sunnah.com/bukhari:7257; Saḥīḥ Muslim 1840 https://sunnah.com/muslim:1840a

[49] Sahih al-Bukhari 4340, https://sunnah.com/bukhari:4340

[50] Ibn Sa’d, Tabaqat, https://shamela.ws/book/1686/487#p1

[51] Ibn Sa’d, Tabaqat, https://shamela.ws/book/1686/486#p1

[52] Dr Ali Muhammad As-Sallabi, ‘Umar ibn al-Khattab, his life and times,’ International Islamic Publishing House, volume 2, p.321

[53] Dr Ali Muhammad As-Sallabi, ‘Umar ibn al-Khattab, his life and times,’ International Islamic Publishing House, volume 1, p.297

[54] Ibid

[55] In the Egyptian constitution Article 201 states, “The Minister of Defense is the Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces, appointed from among its officers.” https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Egypt_2019?lang=ar

[56] In the Egyptian constitution Article 152 states: “The President of the Republic is the Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces. The President cannot declare war, or send the armed forces to combat outside state territory, except after consultation with the National Defense Council and the approval of the House of Representatives with a two-thirds majority of its members.” Ibid

[57] Abu l-Hasan al-Mawardi, Al-Ahkam as-Sultaniyah, Ta Ha Publishers, p.66

[58] Majmoo’ Fatawa al-Shaykh Ibn Uthaymin (12/Question 177), https://islamqa.info/ar/answers/45200/%D8%AD%D9%83%D9%85-%D8%AA%D9%82%D9%84%D9%8A%D8%AF-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%83%D9%81%D8%A7%D8%B1-%D9%88%D9%85%D8%B9%D9%86%D9%89-%D9%85%D8%A7-%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%87-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%B3%D9%84%D9%85%D9%88%D9%86-%D8%AD%D8%B3%D9%86%D8%A7-%D9%81%D9%87%D9%88-%D8%B9%D9%86%D8%AF-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%84%D9%87-%D8%AD%D8%B3%D9%86

[59] https://www.islamweb.net/ar/fatwa/387583/%D8%AA%D9%82%D9%84%D9%8A%D8%AF-%D8%BA%D9%8A%D8%B1-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%B3%D9%84%D9%85%D9%8A%D9%86-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B9%D8%A7%D8%AF%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D8%B1%D8%A4%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D8%B4%D8%B1%D8%B9%D9%8A%D8%A9

[60] Brigadier-General Dr. Muhammad Damir Witr, ‘Al-Idaarah Al-‘Askariyah Fee Hurub Ar-Rasool Muhammad ﷺ),’ ‘The military administration in respect to the wars of the Messenger Muhammad,’ 1986, pp.107-108

[61] Muhammad Khayr Haykal, ‘Al-Jihad wa’l Qital fi as-Siyasa ash-Shar’iyya,’ vol.4, The Eighth Study, Qitaal Mughtasib As-Sultah (The First Study: The different types of organisation that the army)

[62] Ibn Khaldun, ‘The Muqaddimah – An Introduction to History,’ Translated by Franz Rosenthal, Princeton Classics, p.334

[63] Sunan Ibn Majah 2818, https://sunnah.com/urn/1329260

[64] There is a weak hadith in at-Tabarani’s al-Awsat which says that the shahada was written on the liwaa’ and rayah. Hayyan bin Obeidillah told us that Abu Mijlaz Laheq bin Humeid narrated on authority of Ibn Abbas who said: “The rayah of the Messenger of Allah ﷺ was black and his liwaa’ white written on it: لَا إِلَهَ إِلَّا اللَّهُ مُحَمَّدٌ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ”. Ibn Hajar said, وَسَنَدُهُ وَاهٍ “Its chain of transmission is weak.” Some groups have a different opinion on this hadith and use it as evidence for writing the shahada on the liwaa’ and rayah.

The fact that there is no evidence in any hadith of anyone tasked with painting or embroidering letters on to the rayah and the liwaa’, would seem to indicate that both these flags were plain without any writing or symbols on them. This would conform to the simplicity of the first Islamic State where unnecessary time, money and effort was kept to a minimum.

There is also the manat (reality) of the availability of white ‘paint’ at that time which would adhere to the material. All we find repeated by the narrators over and over again in the hadith is the colour. We do not find any mention of symbols and writing except in the disputed isolated ‘hadith’ above.

The rayah has a very detailed description in the hadith, “it was a black square (مُرَبَّعَةً) made from namira (نَمِرَة)” and “The rayah of the Prophet ﷺ was black from the cloak of Aisha.” No mention is made of any writing or attempts at marking the rayah.

For this reason, it is my opinion that we are not obliged to use the shahada on the flags, and any Islamic symbolism is fine. In fact, using any flag or banner to represent the state is of the mubah (permissible) matters since the liwaa’ and rayah were never used in the time of the Prophet ﷺ or Rightly Guided Caliphs except by the army. The liwaa’ and rayah were never attached to the caliph’s house, or attached to Masjid Al-Nabawi. They were kept folded away until the time of an expedition when the liwaa’ would be given (tied) to the Amir.

Due to the likely desecration of the Caliphate’s flags by the enemies of Islam, then having the shahada on them is not advised in order to preserve the sanctity of the names of Allah and His Messenger ﷺ.

[65] Ibn Hajr, Fath al-Bari

[66] Ibn Sa’d, Tabaqat, https://shamela.ws/book/1686/392

[67] Ibn Sa’d, Tabaqat, https://shamela.ws/book/1686/470

[68] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flag_officer

[69] at-Tabarani in al-Kabeer on authority of Mazeeda al-Abdi’

[70] Narrated from Ibn Abi Asem in al-Aahad and al-Mathani on the authority of Kurz bin Sama

[71] Ibn Sa’d, Tabaqat, https://shamela.ws/book/1686/1112

[72] Ibn Sa’d, Tabaqat, https://shamela.ws/book/1686/743

[73] Mohamed Heikal, ‘The Road to Ramadan,’ William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd., London, 1975, p.236

[74] Al-Sarakhsi, Sharh Al-Siyar Al-Kabeer, https://shamela.ws/book/5434/71

[75] Al-Sarakhsi, Sharh Al-Siyar Al-Kabeer, https://shamela.ws/book/5434/72#p1

[76] Ibid

[77] Al-Sarakhsi, Sharh Al-Siyar Al-Kabeer, https://shamela.ws/book/5434/73#p1

Pingback: Al-Mawardi’s Structure of an Islamic State | Islamic Civilization