- Trias Politica – Separation of Powers between the three branches

- Executive Branch

- Legislative Branch

- Judicial branch

- Conclusion

- Notes

It’s widely accepted in political philosophy that there are three branches of government:

| 1 | Executive | implements laws |

| 2 | Legislative | makes laws |

| 3 | Judicial | interprets laws and resolves disputes |

These three branches exist in every ruling system including the Islamic system but differ in their degree of separation.

We can classify such a model under the concept of technical terminology (الاِصْطِلاحات istilahiyyat) which are used to teach and understand Islam. Muhammad Hussein Abdullah says, “It is possible for the people of any particular skill, art or expertise, and in any time period to set terminological conventions (istilahiyyat), utilising the worded expressions (أَلْفاظ alfazh) of the language and transfer them to specific meanings associated to their field.”[1]

There are many technical terms that scholars and thinkers have used to describe the structure of an Islamic State. Al-Mawardi (d.1058) uses ruling spheres (وِلايات wiliyyat). Rashid Rida (d.1936) and Al-Sanhūrī (d.1971) use councils (مَجالِس majalis). Mohammad Barakatullah (d.1927) uses ministries (وِزارَة wizara), and Taqiuddin an-Nabhani (d.1977) uses institutions (أَجْهِزَة ajhizah).

All of these are permissibile as part of the sharia maxim:

لا مُشَاحَّة في الاصطلاح بعد الاتفاق على المعنى

There is no dispute over terminology after agreement on the meaning.[2]

Trias Politica – Separation of Powers between the three branches

Baron de Montesquieu (d. 1755), a French political philosopher, first introduced the idea of these three branches with a view to separating the powers between them.[3] His ideas heavily influenced the founding fathers of America and in particular James Madison, the ‘Father of the Constitution’. This is why these three branches of government are explicitly defined as separate institutions in the American constitution.

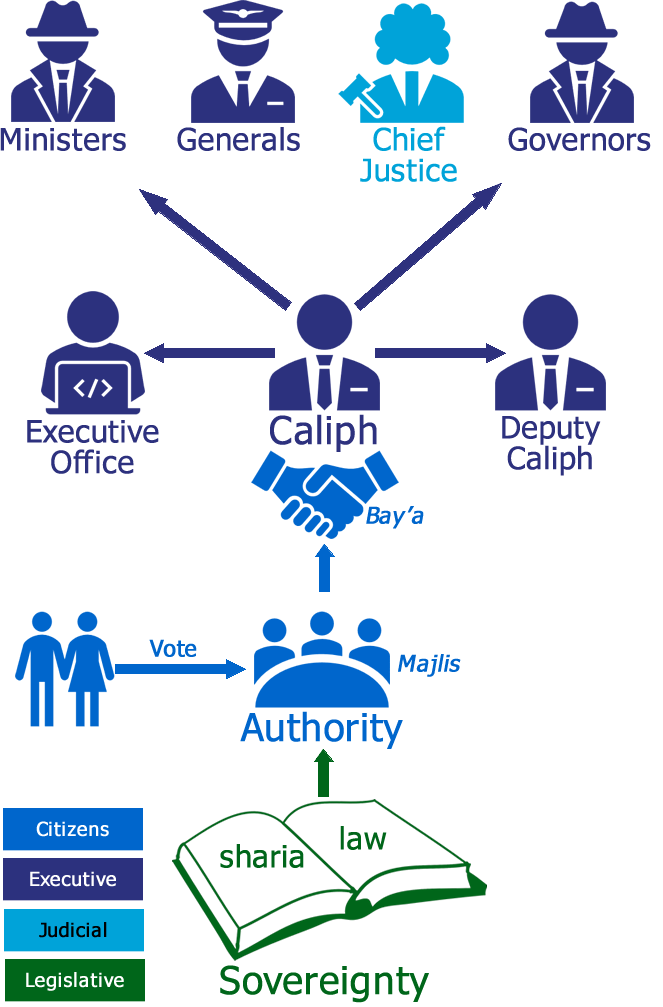

In the US system there is strict institutional separation between the three branches. In other democratic systems such as the UK, the legislative and executive branches are closely linked since the Prime Minister and his cabinet are also members of the legislative parliament. Even in the US system the separation between the executive and legislative is not as distinct as is made out. This is because the President can issue executive orders which effectively make law. Trump’s signing of hundreds of executive orders on entering office is a clear example of this. This is why Mogens Herman Hansen says, “Today Montesquieu’s separation of powers is riddled with so many exceptions that it is an obstacle rather than a help to understand the structure of modern democracy.”[4] Sovereignty in an Islamic State on the other hand is with the sharia and therefore underpins all three branches of government which eliminates such contradictions.

Does this separation of powers also apply to an Islamic State? Al-Sanhuri (d.1971) answers this question. “This brings us to address the question of the separation of powers in Muslim law. It is known that modern public law makes this theory the cornerstone of the constitutional regime. Exaggerated at first in the sense of a complete separation, it was then brought back to its reasonable proportion: distinction of the three powers and coordination between them in the functioning. Muslim law does not consider the judicial power as independent of the executive power. It subordinates the former to the latter, but this subordination has no practical importance, because Caliph and Judge must both bow before the Law, that is to say, before the legislative power.

It is between the executive and judicial powers, on the one hand, and the legislative power, on the other hand, that there is a complete separation, even more rigorous than that which exists in modern law.”[5]

Executive Branch

The Islamic State has a unitary executive, where in origin all executive ruling power is with the caliph. similar to the US President. Article II of the US constitution states, “The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.” This doesn’t make the caliph an absolute monarch or dictator, in the same way it doesn’t make the US president an absolute monarch or dictator, because both posts are restricted by other branches of government namely the legislative branch which is ultimately sovereign.

This power is transferred to the caliph from the ummah who are the source of authority (مَصْدَر السُلْطَة masdar al-sultah)[6] via the bay’a contract. Muhammad Haykal says, “The sultah (authority) in Islam belongs to the Ummah and she passes it to the ruler in accordance to a contract (‘aqd) between her and him upon the basis that he rules her by the Kitab of Allah and the Sunnah of His Messenger ﷺ.”[7]

This executive power is not unconditional because it is restricted by the legislative branch of the state which is the shari’a. Allah (Most High) says,

فَٱحْكُم بَيْنَهُم بِمَآ أَنزَلَ ٱللَّهُ

“So judge/rule between them by what Allah has revealed”[8]

The Prophet ﷺ informed us that those who are charged with this responsibility of ruling are the caliphs. He ﷺ said,

كَانَتْ بَنُو إِسْرَائِيلَ تَسُوسُهُمُ الأَنْبِيَاءُ كُلَّمَا هَلَكَ نَبِيٌّ خَلَفَهُ نَبِيٌّ وَإِنَّهُ لاَ نَبِيَّ بَعْدِي وَسَتَكُونُ خُلَفَاءُ فَتَكْثُرُ قَالُوا فَمَا تَأْمُرُنَا قَالَ فُوا بِبَيْعَةِ الأَوَّلِ فَالأَوَّلِ وَأَعْطُوهُمْ حَقَّهُمْ فَإِنَّ اللَّهَ سَائِلُهُمْ عَمَّا اسْتَرْعَاهُمْ

“The prophets ruled over the children of Israel, whenever a prophet died another prophet succeeded him, but there will be no prophet after me. There will soon be caliphs and they will number many.” They asked; “What then do you order us?” He said: “Fulfil the bay’a to them, one after the other, and give them their dues for Allah will verily account them about what he entrusted them with.”[9]

The Prophet ﷺ described the caliph (imam) as having general powers of responsibility in ruling:

فَالْإِمَامُ الَّذِي عَلَى النَّاسِ رَاعٍ وَهُوَ مَسْئُولٌ عَنْ رَعِيَّتِهِ

“The Imam[10] is a guardian, and he is responsible over his subjects.”[11]

The wording here is mutlaq (unrestricted) so encompasses all types of responsibility over the citizens (رعية). Abdul-Qadeem Zallum (d.2003) comments on this hadith, “This means that all the matters related to the management of the subjects’ affairs is the responsibility of the caliph. He, however reserves the right to delegate anyone with whatever task he deems fit, in analogy with representation (وَكالَة wakala).”[12]

The officials of the state derive their authority from the caliph and are representatives (وُكَلاء wukala’) of him in ruling. Hashim Kamali says, “The head of state, being the wakīl or representative of the community by virtue of a contract of agency/representation thus becomes the repository of all political power. He is authorised, in turn, to delegate his powers to other government office holders, ministers, governors and judges etc. These are, then, entrusted with delegated authority (wilāyat), which they exercise on behalf of the head of state each in their respective capacities.”[13]

Al-Mawardi categorises these representatives into four types:

(i) those who had general powers over the provinces generally, namely wazirs, who were appointed over all affairs without any special assignment;

(ii) those who had general powers in specific provinces, namely the amirs of provinces and districts, who had the right of supervision of all affairs in the particular region with which they were charged;

(iii) those who had specific powers in the provinces generally, such as the qādī al-qudāt [chief judge], the commander in chief (naqīb al-jaysh), the warden of the frontiers (hāmī al-thughūr), the collector of kharāj, and the collector of sadaqāt; and

(iv) those who had specific powers in specific districts, such as the qādī of a town or district, the collector of kharāj or sadaqāt of a district, the warden of a specific frontier district or the naqīb of a local military force.”[14]

These four types of officials cover all executive and judicial appointments by the caliph. This provides the flexibility to create as many institutions as are necessary to run the state at any particular period in time.

An important point to note is that the bay’a contract is to the caliph and not his wakeels. Therefore Al-Mawardi stipulates that the Imam should not over-delegate his authority. He says, “He [Imam] must personally take over the surveillance of affairs and the scrutiny of circumstances such that he may execute the policy of the Ummah and defend the nation without over-reliance on delegation of authority (Al-Tafwid) – by means of which he might devote himself to pleasure-seeking or worship – for even the trustworthy may deceive and counsellors behave dishonestly.”[15]

Legislative Branch

In an Islamic state the legislative branch is the sharia, which binds the caliph, limits his powers and prevents him from overstepping the law. This is primarily achieved through binding the caliph to a constitution when he is given the bay’a on taking office. This is continuously enforced through institutional mechanisms such as the Supreme Court, Majlis al-Nuwaab (House of Representatives) and the Dar al-‘Adl (House of Justice) fulfilling the function of an upper house.

Al-Sanhuri says, “For the Caliph, contrary to what is sometimes said, is not an autocratic sovereign. He has very extensive executive and judicial powers, but he cannot encroach on the legislative domain.”[16]

The Messenger of Allah ﷺ said:

لا تُحْرِجُوا أُمَّتِي ثَلاثَ مَرَّاتٍ ، اللَّهُمَّ مَنْ أَمَرَ أُمَّتِي بِمَا لَمْ تَأْمُرْهُمْ بِهِ ، أَوْ آمُرْهُمْ فَإِنَّهُمْ مِنْهُ فِي حِلٍّ

“Do not oppress or bring difficulty upon my Ummah (he repeated that three times). O Allah, whoever commands my Ummah with that which they have not been commanded with, then they are absolved from him.”[17] [18]

Mohammad Al-Mass’ari comments on this hadith, “It is therefore not permissible for the ruler to impose upon the Ummah a law which has not been deduced by a correct Shar’i deduction, let alone a law that is from man’s production. Similarly, it is prohibited upon the Ummah to obey him in that. This is in addition to other restrictions and conditions related to the obedience to the ruler which have been detailed in our book “The obedience to the Uli l-Amr (rulers): Its limits and restrictions”.

All of this clearly indicates that the siyadah (sovereignty) belongs to the shar’a. Otherwise, it would have been permissible for the ruler to impose laws from other than the Shar’a and compel the Ummah to obey him, due to the generality of the evidences mentioning the obligation of obedience. However, Islam prohibited Muslims to obey the ruler if he commanded them with a ma’siyah (sin), or what is worse than that, in the case where he was to make the Halal Haram, and the Haram Halal. It has been established and indeed by Tawatur (concurrent reports) establishing decisive definite knowledge, in respect to the Muslim and disbeliever, equally, that he ﷺ said:

لاَ طَاعَةَ فِي مَعْصِيَةٍ، إِنَّمَا الطَّاعَةُ فِي الْمَعْرُوفِ

“There is no obedience to anyone if it is disobedience to Allah. Verily, obedience is only in good conduct.”[19]

This separation of powers in Islam was also recognized by orientalists and modern academics who have studied Islamic history.

C.A. Nallino (d.1938) an Italian orientalist and Professor of The History and Institutions of Islam, at The Royal University of Rome in 1919, wrote “While these universal Monarchs [caliphs] of Islam possessed, like any other Mussulman [Muslim] sovereign, limitless executive and judicial powers, they were destitute of legislative powers; legislation in the proper sense of the word could be nothing less than the divine law itself, the sceria [sharia], of which the only interpreters are the ulama or doctors.”[20]

Another orientalist Thomas Arnold (d.1930) a Professor of Arabic and Islamic Studies at SOAS in London wrote: “The law being thus of divine origin demanded the obedience even of the Caliph himself, and theoretically at least the administration of the state was supposed to be brought into harmony with the dictates of the sacred law. It is true that by theory the Caliph could be a mujtahid, that is an authority on law, but the legal decisions of a mujtahid are limited to interpretation of the law in its application to such particular problems as may from time to time arise, and he is thus in no sense a creator of new legislation.”[21]

Wael Hallaq says, “The ruler himself was also expected to observe not only his own code but, more importantly, the law of the Sharīʿa. As a private person, he remained, like any common Sharīʿa subject, liable to any civil claim, including debts, contracts, and pecuniary damages. Likewise, he was punishable for infractions of the Sharʿī penal laws and Qurʾānic ḥudūd —the reasoning in all these domains being grounded in the assumption that all Muslims, weak or strong, are equal in their rights to life and property and in their obligations toward one another. In the Sharīʿa, the sultan and his men enjoyed no special immunity.”[22]

Judicial branch

The caliph also has the power to appoint and dismiss judges, and he himself can be a judge in a case where he has no personal interest. This doesn’t mean however that the judicial branch is with the caliph, because the judiciary in an Islamic State always has decisional independence, which means the judge should be able to decide the outcome of a trial solely based on the law and case itself, without letting the media, politics or other things sway their decision. The Prophet Muhammad ﷺ said:

الْقُضَاةُ ثَلاَثَةٌ وَاحِدٌ فِي الْجَنَّةِ وَاثْنَانِ فِي النَّارِ فَأَمَّا الَّذِي فِي الْجَنَّةِ فَرَجُلٌ عَرَفَ الْحَقَّ فَقَضَى بِهِ وَرَجُلٌ عَرَفَ الْحَقَّ فَجَارَ فِي الْحُكْمِ فَهُوَ فِي النَّارِ وَرَجُلٌ قَضَى لِلنَّاسِ عَلَى جَهْلٍ فَهُوَ فِي النَّارِ ” . قَالَ أَبُو دَاوُدَ وَهَذَا أَصَحُّ شَىْءٍ فِيهِ يَعْنِي حَدِيثَ ابْنِ بُرَيْدَةَ ” الْقُضَاةُ ثَلاَثَةٌ

“Judges are of three types, one of whom will go to Paradise and two to Hell. The one who will go to Paradise is a man who knows what is right and gives judgment accordingly; but a man who knows what is right and acts tyrannically in his judgment will go to Hell; and a man who gives judgment for people when he is ignorant will go to Hell.”[23]

There is no better example of this than when the fourth caliph Ali ibn Abi Talib took a Jew to court and his judge – Qadi Shurayh whom he appointed as Chief Judge in the capital Kufa, ruled against Ali and in favour of the Jew. The Jew said, “The Amir al-Muminin brought me before his Qadi, and his Qadi gave judgement against him. I witness that this is the truth, and I witness that there is no god but Allah and I witness that Muhammad is the Messenger of Allah, and that the armour is your armour.”[24]

Another example is the Abbasid Caliph al-Ma’mun (r.813-833CE), who used to personally sit in the Mazalim Court every Sunday. One day a woman in rags came to the court and confronted al-Ma’mun complaining that her land had been seized. Al-Ma’mun asked her: “Against whom do you lodge a complaint?” She replied: “The one standing by your side, al-‘Abbas, the son of the Amir of the Believers.” Al-Ma’mun then told his Qadi, Yahya ibn Aktam, (while others say that it was his wazir Ahmad ibn Abi Khalid), to hold a sitting with both of them and to investigate the case – which he did in the presence of al-Ma’mun.”[25] Since the case involved the caliph’s son, al-Ma’mun deferred it to his Chief Qadi similar to what Ali ibn Abi Talib had done.

Wael Hallaq says, “It was this paradigmatic law that was applied in the courts of the Islamic world, and it was applied, as a rule, faithfully by a judicial order committed to the letter and spirit of the law’s moral and just constitution. If it is true, as Kelsen argued, that “democracy requires that the legislative organ should be given control over the administrative and judicial organs,”166 then the Islamic form of governance amply provides for such a democratic system, since the Islamic judicial and executive branches remained—insofar as society was concerned—under the control of the “legislative” power.

But we have also seen that there is more than one reason to claim this system to be highly representative. However, the point here is even more emphatic. Islamic governance separated the executive power from the legislative by degrees, making the former wholly subservient to the will of the latter, the supreme moral law. The law of the courts was also independent, despite the executive’s prerogative to appoint and dismiss qāḍīs. This prerogative was more nominal than substantive, for notwithstanding judicial appointments and dismissals, the paradigmatic law applied by the qāḍīs always remained that of the Sharīʿa.”[26]

Conclusion

True separation of powers will only be achieved in an Islamic State that makes the sharia sovereign in all spheres of state and society.

Wael Hallaq says, “Whereas the modern state rules over and regulates its religious institutions, rendering them subservient to its legal will, the Sharīʿa rules over and regulates, directly or through delegation, any and all secular institutions. If these institutions are secular or deal with the secular, they do so under the supervising and overarching moral will that is the Sharīʿa.

Therefore, any political form or political (or social or economic) institution is ultimately subordinate to the Sharīʿa, including the executive and judicial powers. The Sharīʿa itself, on the other hand, is the “legislative power” par excellence. Unlike the modern state, in Islamic governance the Sharīʿa is unrivaled in this domain, and no power other than it can truly legislate. There is no judicial review in Islam, and so the judiciary could never directly contribute to legislation, as we shall see in more detail later. [27]

Notes

[1] Muhammad Hussein Abdullah, ‘Al-Waadih Fee Usool ul-Fiqh,’ 1995, First Translated English Edition 2016, p.555

[2] https://www.alukah.net/sharia/0/25041/%D9%82%D8%A7%D8%B9%D8%AF%D8%A9-%D9%84%D8%A7-%D9%85%D8%B4%D8%A7%D8%AD%D8%A9-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A7%D8%B5%D8%B7%D9%84%D8%A7%D8%AD/#_ftnref22

[3] Charles de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu, The Spirit of Laws, Translated by Thomas Nugent, revised by J. V.Prichard, Based on an public domain edition published in 1914 by G. Bell & Sons Ltd., London

[4] Hansen, Mogens Herman. “THE MIXED CONSTITUTION VERSUS THE SEPARATION OF POWERS: MONARCHICAL AND ARISTOCRATIC ASPECTS OF MODERN DEMOCRACY.” History of Political Thought, vol. 31, no. 3, 2010, pp. 509–31. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26224146.

[5] ʻAbd al-Razzāq Aḥmad Sanhūrī, Le Califat, Son Évolution Vers Une Société Des Nations Orientale, Travaux Du Séminaire Oriental d’études Juridiques et Sociales … t. 4 (Paris: P. Geuthner, 1926). P.5

[6] Hashim Kamali, ‘Citizenship and Accountability of Government: An Islamic Perspective,’ The Islamic Texts Society, 2011, p.197

[7] Muhammad Khayr Haykal, ‘Al-Jihad wa’l Qital fi as-Siyasa ash-Shar’iyya,’ vol.1, The Eighth Study, Qitaal Mughtasib As-Sultah (Fighting the usurper of the authority)

[8] Holy Qur’an, Surah Al-Ma’ida, ayah 48

[9] Sahih Muslim 1842a, https://sunnah.com/muslim:1842a ; sahih Bukhari 3455, https://sunnah.com/bukhari:3455

[10] Imam here means the khaleefah i.e. the great Imam الْإِمَامُ الْأَعْظَمُ. Ibn Hajar, Fath al Bari, https://shamela.ws/book/1673/7543#p1

[11] Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī 7138, Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim 1829

[12] Abdul-Qadeem Zallum, ‘The Ruling System in Islam,’ translation of Nizam ul-Hukm fil Islam, Khilafah Publications, Fifth Edition, p.111

[13] Hashim Kamali, ‘Separation of powers: An Islamic perspective,’ IAIS Malaysia, p.473; https://icrjournal.org/index.php/icr/article/view/370/348

[14] Ann K. S. Lambton, ‘State and Government in Medieval Islam,’ Oxford University Press, 1981, p.95

[15] Abu l-Hasan al-Mawardi, Al-Ahkam as-Sultaniyah, Ta Ha Publishers, p.28, https://shamela.ws/book/22881/35

[16] ʻAbd al-Razzāq Aḥmad Sanhūrī, Le Califat, Son Évolution Vers Une Société Des Nations Orientale, Travaux Du Séminaire Oriental d’études Juridiques et Sociales … t. 4 (Paris: P. Geuthner, 1926). P.5

[17] Al-Tabarani, 826, https://hadith.islam-db.com/single-book/480/%D9%85%D8%B3%D9%86%D8%AF-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B4%D8%A7%D9%85%D9%8A%D9%8A%D9%86-%D9%84%D9%84%D8%B7%D8%A8%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%86%D9%8A/0/826

[18] Mohammad Al-Mass’ari, Al-Haakimiyah Wa Siyaadat ush-Shar’i

[19] Muttafaqun Alayhi (agreed upon). Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī 7257 https://sunnah.com/bukhari:7257; Saḥīḥ Muslim 1840 https://sunnah.com/muslim:1840a

[20] C.A. Nallino, ‘Notes on the nature of the caliphate in general and on the alleged Ottoman Caliphate,’ a translation of ‘Appunti sulla natura del Califfato in genere e sul presunto Califfato Otttomano,’ Printed at the press of the foreign office, Rome 1919, p.7

[21] Thomas W. Arnold, ‘The Caliphate,’ p.53

[22] Wael B. Hallaq, ‘The Impossible State: Islam, Politics, and Modernity’s Moral Predicament,’ Columbia University Press, p.68

[23] Sunan Abi Dawud 3573, https://sunnah.com/abudawud:3573

[24] Jalal ad-Din as-Suyuti, ‘History of the Khalifahs who took the right way,’ translation of ‘Tarikh al-Khulafa,’ Ta Ha Publishers, p.139

[25] al-Mawardi, Op.cit., p.128

[26] Wael B. Hallaq, Op.cit., p.71

[27] Wael B. Hallaq, Op.cit., p.51