- Transforming Yathrib to Al-Medina Al-Munawwarah

- What is a state?

- Was Medina a state?

- The Five Institutions of State

- The Institutions of the Islamic State in Medina

- Solidifying the State

- Transformation to empire

- Notes

The emergence of the first Islamic State in 622CE went unnoticed at first by the Sassanid and Byzantine empires. The Persians and Romans were fighting each other in a major war[1], and so their focus was not on the nomadic Arabs who had never previously posed any type of threat to their empires.

John Saunders says, “Once and once only, did the tide of nomadism flow vigorously out of Arabia. Bedouin raids on the towns and villages of Syria and Iraq had been going on since the dawn of history, and, occasionally an Arab tribe would set up a semi-civilized kingdom on the edge of the desert, as the Nabataeans did at Petra or the Palmyrenes at Tadmur, but conquests only occurred at the rise of Islam.”[2]

What precipitated these conquests, and the establishment of an empire and civilisation which lasted as a state in one form or another for 1300 years is a miraculous achievement. Within thirty years of the Islamic State’s establishment in Medina, the Persian Empire fell, and the Romans were confined to modern day Türkiye after losing all their territory in Ash-Sham, Egypt, North Africa and their naval dominance in the Mediterranean.

Transforming Yathrib to Al-Medina Al-Munawwarah

On entering Medina after the hijra (migration) from Mecca, the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ embarked on transforming the divided tribal society of Yathrib, into Al-Medina Al-Munawwarah (The Enlightened City). This new society would be a state based on the ideology of Islam where the old tribal bonds (asabiyah) were replaced with a new bond, that of Islam and brotherhood. The old tribal law was replaced with a new divine law – sharia, and a new vision of spreading the message of Islam (daw’ah) to the world through conquest was nurtured among its people.

Fred Donner says, “It is therefore essential to note that the embryonic Islamic state created by Muhammad displayed certain features giving it considerably more cohesiveness and a more thoroughly centralized structure than was found in normal Arabian tribal confederations. It is in these novel features that the impact of the new ideology of Islam upon the solid political accomplishments of Muhammad’s career is most clearly visible-indeed, it was the new ideology that gave those accomplishments durability and made of them the foundation of the conquest movement.”[3]

The Prophet ﷺ began laying the foundations of this new state and establishing institutions to look after people’s affairs. He ﷺ built a mosque – Masjid Al-Nabawi – which became the centre of the state acting like a government headquarters. Foreign dignitaries would be hosted in the masjid, important communications were delivered from the minbar (pulpit) and government officials and army commanders were given their orders from there.

Part of the masjid was converted into a shelter for the poor and homeless Muslims known as Ahl Al-Suffah. This was more than a simple housing shelter. It was an educational establishment where the occupants spent their time in learning and development, playing important roles as soldiers in the battles, and in running the state long after the Prophet ﷺ had passed away. Abu Huraira is one of the graduates of Ahl As-Suffah, which is why he is the top narrator of hadith as he spent so much time with the Prophet ﷺ learning and memorising. During the caliphate of Umar ibn al-Khattab he was appointed as the governor of Bahrain.

A new ‘constitutional document’ called the Sahifa (Medina Charter) was written which governed the relationships between the Muslims, and between the Muslims and the Jewish tribes in and outside Medina. This document firmly established the Prophet ﷺ as head of the new state, and the sharia as its governing law. Rached Ghannouchi says, “The Medina Charter created the necessary basis for an open political and civilizational space that would extend around the globe, encompassing without exception all the peoples, civilizations, religions, and tribes it encountered in its path, opening the way for mutual engagement with one another within this space and for joint participation in creating the contours of this new society.”[4]

A new marketplace was established to stimulate economic activity in the mainly farming community of Medina famous to this day for its date palms.

Finally, he ﷺ appointed a wide array of government officials (‘ummal عُمّال) from the sahaba to manage the affairs of the state. Wazirs, private secretaries, scribes, tax collectors, army commanders, foreign envoys, teachers, media representatives, market inspectors, regional judges and governors were all appointed to run the state.

Fred Donner says, “The advent of a notion of divine law that was the duty of believers to obey, then, set the stage for a more orderly approach to social and political relations. It may, furthermore, have eased the way for the rise of a state bureaucracy-so necessary to the functioning of a state, yet alien to the pre-Islamic political scene in northern and central Arabia. For with the acceptance of the idea of a supreme authority transcending tribal affiliations, it became possible for believers to accept administrators who were representatives of that authority. It was a situation in marked contrast to the pre-Islamic setting, in which only representatives of one’s own tribe, or of a dominant tribe, would have been heeded.”[5]

In the beginning the Prophet ﷺ took a much more hands on role leading most of the major battles himself and managing most of the affairs of state himself. He ﷺ managed and participated in the building of Masjid Al-Nabawi. He ﷺ acted as a judge for all disputes in Medina, and he ﷺ distributed funds to the people. Later he delegated duties to the sahaba as they became more competent and skilled in the affairs of state. This is most stark in the military expeditions. An expedition led by the Prophet ﷺ is called a ghazwa, and those led by a sahabi are known as a sariyya.

This shows that there was a clear tarbiyyah (training) programme preparing the sahaba to continue running the state and expanding it after his ﷺ death. As an example, Zayd bin Thabit was a secretary to the Prophet ﷺ. He was tasked with translating the letters of the Jews and learnt Hebrew in 15 days. In Abu Bakr’s caliphate he continued to be a secretary. In Umar’s caliphate he was a deputy caliph, teacher in Medina and head of the judiciary, roles which he continued to hold under Uthman bin Affan.

This tarbiyyah programme started in Mecca in Dar al-Arqam, and continued throughout the Prophet’s ﷺ life in Medina. Muhammad As-Sallabi says, “In less than one half of a century, the singularly superior men that the Prophet educated were blessed with many great victories as they carried the message of Tawheed (Islamic Monotheism) all over the world. In the early years of his Prophethood, the Messenger of Allah wisely chose and trained the key people that would be needed to lead the Muslim nation through its glorious first century of being. It is with that end in mind – the spread of Islam all over Arabia and to many parts of the world – that we can truly appreciate the early days of education and training in the house of Al-Arqam.”[6]

When the Persian governor of Yemen Bādhān ibn Sāsān embraced Islam, the Prophet ﷺ kept him in place as As-Sallabi describes, “Kisra’s viceroy to Yemen was Bādhān ibn Sāsān. During the Prophet’s lifetime, Bādhān embraced Islam, and the Prophet ﷺ recognizing good leadership qualities in Bādhān allowed him to remain governor of Yemen. It was always the case that the Messenger of Allah ﷺ appointed people based on their qualities and on the job performance that could be expected of them. The Prophet ﷺ knew that Bādhān was an experienced leader and that he was well-acquainted with the people of Yemen and with their needs; thus he, and not a person of high-ranking from Mecca or Al-Madeenah, was best suited for the job; hence the Prophet’s decision to allow Bādhān to stay on as governor.”[7]

What is a state?

When we study the Islamic texts i.e. the Qur’an and Sunnah, we do not find reference to the word “state” (دَوْلَة dawla) in reference to ruling and politics. The word “state” is a technical (istilah) term whose meaning has evolved over the centuries, but in its current usage means “a politically organized body of people usually occupying a definite territory.”[8]

Muhammad Hussein Abdullah says, “It is possible for the people of any particular skill, art or expertise, and in any time period to set terminological conventions (istilahiyyat), utilising the worded expressions (أَلْفاظ alfazh) of the language and transfer them to specific meanings associated to their field.”[9]

Fred Donner says, “The very concept of the “state” as a political organism or institution is relatively recent—a product of European political development and political philosophy of the fifteenth century and later. Before this time, we find references to “kingdom”, “empire”, “sovereign city (polis)” and so on, but in no European language does there seem to have existed a term or concept that is equivalent to the modern concept of the “state”. This is also certainly true of the early Islamic world, which used terms such as khilafa (“caliphate”), imara (“amirate”), or mamlaka (“kingdom”). The word dawla, which means “state” in modern Arabic, was used in early Islamic times, but in the sense of “turn of fortune”, hence “turn in power”; it only acquired its modern meaning in later centuries.[10]

Nonetheless, following the emergence of the term and concept of “the state” in European discourse, it has become commonplace to attempt to define the “state” and to identify examples of political organizations that fit the definition even in remote antiquity. Because the state is not a natural (ontological), but rather a social (constructed), phenomenon, however, definitions of it have varied in response to the diverse realities of particular political organisms and to the perceptions and concerns of the observer.”[11]

The Encyclopaedia of Islam describes the origins and transformation of the term dawla in Arabic. “It seems that at the beginning of the Abbasid period, the term dawla was by no means well established in the meaning of “dynasty”. However, the word was frequently used by the Abbasids with reference to their own “turn” of success. Thus it came to be associated with the ruling house and was more and more used as a polite term of reference to it. Soon, one could speak of the supporters and members (ashab, rijal) belonging to the dawla, the supporters and members of the dynasty; again, the precise date of the earliest occurrence of such usage as yet eludes us.”[12]

Was Medina a state?

While there is ‘ijma ‘ulema that the Prophet ﷺ established a state and the elements of a state in Medina, some modernists and orientalists in the 20th century began to dispute this fact. Most famous of these is Ali Abdel Razek who was an ‘Alim and Judge in Egypt under British occupation, and a graduate from Al-Azhar university. In 1925 he published a book ‘Islam and the Foundations of Governance’ (Al-Islam Wa Usul Al-Hukm) which in summary said, “Islam does not advocate a specific form of government.”[13]

Ali Abdel Razek said, “On inquiring into the judicial system of the times, we realise that neither this nor the other institutions and practices typical of any government existed in a clear or unequivocal shape during the lifetime of the Prophet. An objective scholar can conclude from this that the Prophet never in fact appointed a governor to keep order and administer the affairs in territories which God placed at his command. Everything that has been reported on this subject leads us to the conclusion that the Prophet from time-to-time delegated certain limited functions, such as command over troops, supervision of property, leadership of the prayer, instruction in the Qur’an, and the propagation of the faith, to certain individuals. These assignments were not continuous or permanent, as we can see from examples of pronouncements during military missions or expeditions; as well as from the examples of appointing a deputy during the Prophet’s absences from Medina while at war.”[14]

This book went against ‘ijma and as a result Ali Abdel Razek was stripped of his ‘Alim ijaza (permission to teach).

The Council of scholars at Al-Azhar gave a detailed response refuting all his claims. In summary in relation to charge 3 which is relevant to our discussion here they said,

“CHARGE 3 – That he claims that the system of ruling in the era of the Prophet was the subject of uncertainty, ambiguity, turbulence or shortcomings and so is perplexing.

This is a clear statement from Sheikh Ali which proves the charge. If he admits to some of the systems of governance in Islamic law, then he contradicts his admission, and decrees that these systems are nonexistent.

…

We, the Sheikh of the University of al-Azhar along with the unanimous agreement of twenty-four scholars from the Council of Senior Scholars, judged Sheikh Ali Abdul Raziq, a member of the University of al-Azhar and a Shari’ah judge in the Primary Shari’ah Court of Mansoorah and the author of the book (Islam and governance) be expelled from the community of scholars.

The Office of General Administration of the Religious Institutions issued this judgement on Wednesday 22 Muharram 1344 (August 12 1925).” [15]

Signed: the Sheikh of the University of al-Azhar[16]

Rached Ghannouchi says, “The structure of the Islamic state that developed in Medina at the time of the Messenger ﷺ and the Rightly Guided Caliphs provided all the elements necessary to any state, namely a people [umma], a territory, a political authority, and a legal system.”[17] He continues, “It seems hard to imagine that anyone could deny the reality of the political society that arose in Medina after the Hijra. This was a remarkable body politic, independent as to its territory, its unified laws, and its leadership, its inhabitants tied together by common relations, texts, and goals. Further, this society exercised all the functions of a state, including defense and justice, and the authority to ratify treaties and send out emissaries. No one among those who built this system had any doubt about its nature. Supreme legislative authority belonged to God and His Messenger (the Book and the Sunna), and the other sources of law like ijtihad were secondary sources to be used within the frame of reference and supreme legal framework of the Qur’an and Sunna—that is, guided by divine revelation and its objectives.”[18]

The Five Institutions of State

For the purposes of this article, we will use Fred Donner’s definition of a state where he says, “The state, then, can be described as having an ideology of Law, coupled with certain definable institutions. The institutions intrinsic to the state are, generally, those needed to establish its Law and to maintain the political order. These we can consider to be the following:

(a) a governing group

(b) means for preserving the position of the governing group in the political hierarchy against both external and internal threats, i.e. an army and police

(c) means for providing for the adjudication of disputes in the society i.e. a judiciary

(d) means for paying for state operations, i.e. a tax administration

(e) institutions to perform other aspects of policy implicit in the legal and ideological foundations of the state”[19]

When we apply these criteria to Medina, we can clearly see that the Prophet ﷺ did establish a state with all the institutions mentioned by Donner. The actual institutions and offices of state were very basic due to the reality of Arabia during that period, and the time and resources available to develop them.

What is clear though is that the Prophet ﷺ was not creating any ordinary state. He ﷺ was laying the foundations of a state which would transform in to a global empire[20] and civilisation that would eventually encompass the entire world. He ﷺ said,

وَكَانَ النَّبِيُّ يُبْعَثُ إِلَى قَوْمِهِ خَاصَّةً، وَبُعِثْتُ إِلَى النَّاسِ كَافَّةً

“Every Prophet used to be sent to his nation exclusively but I have been sent to all humankind.”[21]

| Institution | Medina |

| a governing group | Prophet Muhammad ﷺ was the head of the government. He had assistants and secretaries which in modern day translate to an Executive Office and Executive Departments. |

| means for preserving the position of the governing group in the political hierarchy against both external and internal threats, i.e. an army and police | There was no standing army because in Nomadic Arabia the tribes would be the fighting unit. However, the Prophet ﷺ would organise the army expeditions and appoint the commanders. For the major battles he would organise the tribes in the battle similar to a commander assigning regiments in the modern day. There were guards and patrols in Medina which can be considered as shurta (police) |

| means for providing for the adjudication of disputes in the society i.e. a judiciary | The Prophet ﷺ combined all three branches of government executive, judicial and legislative since he was a prophet. In Media he ﷺ would perform the function of judiciary, but when the state expanded and became an ‘empire’ he ﷺ appointed judges for the provinces such as Mecca and Yemen. |

| means for paying for state operations, i.e. a tax administration | A number of new centralised taxes on agriculture, trade, war booty and wealth were introduced. |

| institutions to perform other aspects of policy implicit in the legal and ideological foundations of the state”[22] | State administrative functions were implemented as required to look after the affairs of the people. |

Fred Donner says, “The transition to state organization was, of course, a gradual process; one cannot isolate any specific moment at which the Islamic state can be said to have come into existence. But it is clear that Muhammad, by the end of his career, controlled a polity that had in some measure acquired the main characteristics of a state: a relatively high degree of centralization, a concept of the primacy of law or centralized higher authority in the settlement of disputes, and institutions to perform administrative functions for the state existing independent of particular incumbents. For want of a precise moment, we can select the hijra in A.D.622 and the start of Muhammad’s political consolidation in Medina as the point at which the rise of the new Islamic state begins.”[23]

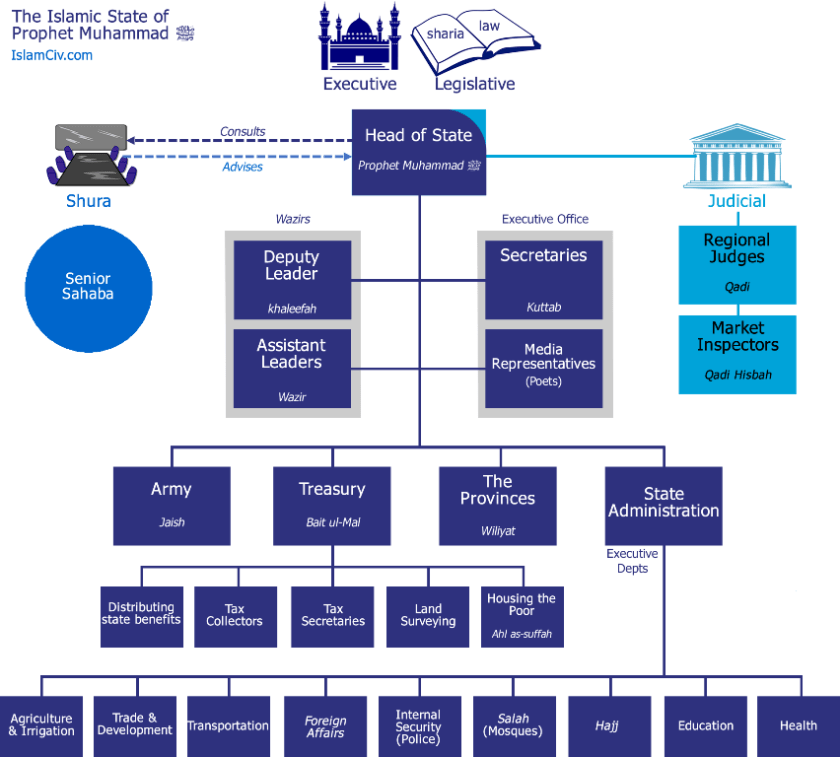

The Institutions of the Islamic State in Medina

Contrary to those who claim otherwise, when we study the seerah of the Prophet ﷺ we can derive a number of principles and institutions of ruling which show that Medina was a state. Although the styles and means related to these institutions developed over time, the underlying principles were there. For example, the Bait ul-Mal (State Treasury) started off as an upper room (مَشْرُبَةٍ) in the Prophet’s ﷺ house.[24] It then became a separate building in the time of the Rightly Guided Caliphs before becoming a room on an elevated platform only accessible by ladder during the Umayyad period.

This transformation from simple state infrastructure to fully fledged institutions continued throughout the caliphate’s history. Today we can adopt all types of styles and means, technology and administrative principles within certain broad limits of the sharia, to create as many institutions as are required to run a modern state.

Having said this, the Islamic ruling system will inevitably share characteristics with other forms of government, since the top-level institutions such as having a ruler, judiciary, military, police, executive departments and so forth are the same for all ruling systems. What distinguishes them is the underlying ideology and foundations upon which the state is built.

We can see this in the Prophet’s ﷺ state. Appointing government posts and establishing institutions was by no means unique, as the Romans and Persians had governors, ministers, armies, police, taxation, currency etc. What made Medina unique however is the underlying ideology of Islam.

As an example, taxation in the Prophet’s ﷺ state was not oppressive and did not bankrupt the poor as happened in the Persian and Roman domains where someone in debt could actually be enslaved. Islam came and abolished this. The high conduct of the Muslim armies and the kind treatment of non-Muslim citizens (dhimmi) in the newly acquired provinces of Bahrain and Yemen was something stark to what went before. This is why the Christians of Homs said to the Muslim army led by Abu Ubaidah during the conquest of Syria, “Your rule and justice are dearer to us than the oppression that we used to suffer [under the Byzantines].”[25]

Sayyid Qutb comments on the similarity in governing structures. “It may happen, in the development of human systems, that they coincide with Islam at times and diverge from it at others. Islam, however, is a complete and independent system and has no connection with these systems, neither when they coincide with it nor when they diverge from it. For such divergence and coincidence are purely accidental and in scattered parts. Similarity or dissimilarity in partial and accidental matters is also of no consequence. What matters is the basic view, the specific concept from which the parts branch out. Such parts may coincide with or diverge from the parts of other systems but after each coincidence or divergence Islam continues on its own unique direction.”[26]

This is a logical structure mapped to how modern states are organised in order to better understand the Prophet’s ﷺ state structure.

| Institution | Medina |

| Head of State | Prophet Muhammad ﷺ |

| Wazirs (Ministers) | Deputy Leader in Medina |

| Assistant Leaders | |

| Executive Office | Secretaries (Kuttab) |

| Media Representatives (Poets) | |

| Army | |

| Provinces | |

| Judiciary | Regional Judges |

| Market Inspectors (hisba) | |

| Treasury | Distributing state benefits |

| Tax Collectors | |

| Tax Secretaries | |

| Land Surveying | |

| Housing the Poor (Ahl as-Suffah) | |

| State Administration (Executive Departments) | Trade & Development |

| Agriculture & Irrigation | |

| Transportation (roads) | |

| Internal Security (Police) | |

| Salah and Mosques | |

| Hajj | |

| Education | |

| Health | |

| Foreign Affairs |

For a full picture of the actual structure and the name of those sahaba who held positions please see the book “History of the Islamic State’s institutions”.

The Prophet Muhammad ﷺ was a ruler-prophet and so held all three branches of government, executive, legislative and judicial, although legislation (sharia) was not from him ﷺ but from Allah (Most High):

وَمَا يَنطِقُ عَنِ ٱلْهَوَىٰٓ إِنْ هُوَ إِلَّا وَحْىٌۭ يُوحَىٰ

“He does not speak from his own desire. It is only a revelation sent down ˹to him˺.”[27]

As the state expanded most notably to Yemen, he then appointed separate judges for the new provinces, and new governors. Ali ibn Abi Talib was appointed as Qadi (judge) for Yemen. It was narrated that ‘Ali ibn Abi Talib said:

عَنْ عَلِيٍّ، رَضِيَ اللَّهُ عَنْهُ قَالَ بَعَثَنِي رَسُولُ اللَّهِ صَلَّى اللَّهُ عَلَيْهِ وَسَلَّمَ إِلَى الْيَمَنِ فَقُلْتُ إِنَّكَ تَبْعَثُنِي إِلَى قَوْمٍ وَهُمْ أَسَنُّ مِنِّي لِأَقْضِيَ بَيْنَهُمْ فَقَالَ اذْهَبْ فَإِنَّ اللَّهَ سَيَهْدِي قَلْبَكَ وَيُثَبِّتُ لِسَانَكَ

“The Messenger of Allah ﷺ sent me to Yemen. I said: ‘You are sending me to people who are older than me for me to judge between them.’ He said: ‘Go, for Allah will guide your heart and make your tongue steadfast.’”[28]

After the death of Yemen’s governor Bādhān ibn Sāsān, the Prophet ﷺ split Yemen in to two provinces and appointed a sahabi over each. It seems that this was to teach the sahaba the skills of ruling because one large province would be too much for an inexperienced ruler to govern. Abu Burda narrates,

عَنْ أَبِي بُرْدَةَ، قَالَ بَعَثَ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم أَبَا مُوسَى وَمُعَاذَ بْنَ جَبَلٍ إِلَى الْيَمَنِ، قَالَ وَبَعَثَ كُلَّ وَاحِدٍ مِنْهُمَا عَلَى مِخْلاَفٍ قَالَ وَالْيَمَنُ مِخْلاَفَانِ

“The Messenger of Allah ﷺ sent Abu Musa and Mu’adh bin Jabal to Yemen. He sent each of them to administer a province (مِخْلاَفٍ) as Yemen consisted of two provinces.”[28.5]

The Prophet ﷺ therefore began to delegate executive and judicial power as the state expanded.

Solidifying the State

“The Messenger of Allah ﷺ and his Companions remained in Mecca, after the advent of the revelation, for ten years in a state of fear: sleeping at night and waking in the morning with weapons at their sides. Then the Prophet was commanded to migrate to Medina. One of his Companions asked him: ‘O Messenger of Allah, there is not a single day in which we feel safe such that we can put down our weapons.’ The Messenger of Allah ﷺ said: ‘It will not be long before one of you will be sitting unarmed amidst huge numbers of people, none of whom carries a weapon.’

Then, Allah, exalted is He, revealed:

وَعَدَ اللَّهُ الَّذِينَ آمَنُوا مِنْكُمْ وَعَمِلُوا الصَّالِحَاتِ لَيَسْتَخْلِفَنَّهُمْ فِي الْأَرْضِ كَمَا اسْتَخْلَفَ الَّذِينَ مِنْ قَبْلِهِمْ وَلَيُمَكِّنَنَّ لَهُمْ دِينَهُمُ الَّذِي ارْتَضَىٰ لَهُمْ وَلَيُبَدِّلَنَّهُمْ مِنْ بَعْدِ خَوْفِهِمْ أَمْنًا ۚ يَعْبُدُونَنِي لَا يُشْرِكُونَ بِي شَيْئًا ۚ وَمَنْ كَفَرَ بَعْدَ ذَٰلِكَ فَأُولَٰئِكَ هُمُ الْفَاسِقُونَ

“Allah has promised those of you who believe and do righteous actions that He will certainly make them successors in the land, as He did with those before them; and will surely establish for them their faith which He has chosen for them; and will indeed change their fear into security—˹provided that˺ they worship Me, associating nothing with Me. But whoever disbelieves after this ˹promise˺, it is they who will be the rebellious.”[29]

Consequently, Allah, exalted is He, enabled His Prophet ﷺ to have the upper hand over the Arabian Peninsula, and the Muslims were able to put down their weapons and feel safe. They remained safe after Allah, exalted is He, took to Himself His Prophet, and during the reign of Abu Bakr, ‘Umar and ‘Uthman, may Allah be well pleased with them. When they fell into that which they fell and were ungrateful, Allah brought fear into their hearts; they changed and so Allah, exalted is He, changed what they had.”[30]

This change in Medina from fear to security and peace only occurred after the signing of the Treaty of Hudaibiyah, and the conquest of Khaibar six years after the Hijra. Allah (Most High) describes the treaty as a “clear victory”:إِنَّا فَتَحْنَا لَكَ فَتْحًا مُّبِينًا “Indeed, We have granted you a clear victory”[31] Yasir Qadhi explains the reasoning behind this, “The Treaty of Ḥudaybiyyah, despite its drawbacks, marked the first instance wherein the Quraysh recognised the Muslims as an independent entity. It was a turning point in the sīrah, and the Quraysh had accepted that the Muslims were here to stay.”[32] He continues, “Until Ḥudaybiyyah, the Muslims had been living under a constant threat, which had officially ended. The Battle of the Trench showed that even their safe haven of Medina could be attacked, but the Treaty of Ḥudaybiyyah guaranteed at least ten years of safety and security. This newfound security allowed the Prophet to finally spread the Message of Islam globally, writing to international leaders.”[33]

It was also at this time that the Prophet ﷺ sent a message to the Muslims living in the Kingdom of Aksum in Abyssinia, to come to Medina. Before this time, it seems that the Prophet ﷺ was keeping Abyssinia as a plan B in case the state of Medina fell.

During the Meccan period, a number of Muslim families migrated to Abyssinia to escape the persecution of the Quraysh. The Kingdom of Aksum was ruled by a just Christian king known as the Negus (Najashi). Sayyid Qutb (d.1966) describes this event as not just a means of escaping repression, but part of a larger plan by the Prophet ﷺ. “The Messenger of Allah ﷺ was searching for a stronghold outside of Makkah, a stronghold that could protect the beliefs of Islam and guarantee the freedom to openly practice Islam. In my estimation, this was the foremost reason that prompted the migration (to Abyssinia). The view which states that the Prophet’s ﷺ Companions migrated only to save themselves is not corroborated by strong evidence. Had they migrated only to save themselves (from torture and temptation to leave the fold of Islam), those Muslims who were weakest – in status, strength, and protection – would have migrated as well, but the fact is that slaves and weak Muslims, who bore the major grunt of persecution and torture, did not migrate. Only men who had strong tribal ties – ties that protected them from torture and temptation – migrated to Abyssinia. In fact, the majority of those who migrated were members of the Quraish (as opposed to imported slaves or weak Muslims who lived in Makkah but were not from the Quraish, such as the family of Yasir.)”[34]

Al-Ghadban in his seerah writes, “This poignant observation from Sayyid Qutb (may Allah have mercy on him) is supported by events in the Seerah (the Prophet’s biography). In my view, the strongest evidence of that is the overall result of their migration to Abyssinia. From what we know (i.e., from what is related in historical narrations), the Messenger of Allah didn’t send for those who migrated to Abyssinia until after (the Prophet’s) migration to Yathrib (i.e., Al-Madeenah), Badr, Uhud, Khandaq, and Al-Hudaibiyyah. For a total of five years (after the Prophet’s migration), Yathrib was vulnerable to complete destruction at the hands of the Quraish. The last of Quraish’s attacks and attempts of destroying (the Muslims in Al-Madeenah) occurred during (the Battle of) Al-Khandaq. After this battle, when the Messenger of Allah ﷺ felt certain that Al-Madeenah was a safe stronghold for Muslims – there being no more danger of an impending attack from the polytheists – he ﷺ summoned those who had migrated to Abyssinia. There was no longer any need to keep a precautionary base in Abyssinia, where the Prophet ﷺ would have possibly been able to seek refuge had Yathrib fallen into the hands of the enemy.”[35]

Transformation to empire

Up until the signing of the Treaty of Hudaibiyah in 6 Hijri (628CE) the state remained fairly static in terms of its size. It was only after the signing of this treaty that things began to change. One of the key conditions which made it a “clear victory” was:

“Any third party that wants to enter into an agreement or alliance with Muhammad has the right to do so. And any third party that wants to enter into an agreement or alliance with the Quraish has the right to do so.”[36]

This allowed the tribes of Arabia to make alliances with the Islamic State in Media without fear of sanctions from the Quraysh. Consequently, the Khuzaa’ah tribe entered into the agreement, saying, “We are upon an agreement and a covenant with Muhammad”; and the people of Banu Bakr also entered into the agreement, saying, “We are upon an agreement and a covenant with the Quraish.”[37]

Now that the Prophet ﷺ was freed up to make alliances with any tribes without interference from Quraysh, he sent a series of letters to all the empires, kingdoms and major tribes of Arabia and beyond including Egypt and Abyssinia.

Ibn Shihāb al-Zuhrī, one of the greatest scholars of the Tabi’in (successors), comments, “There was no greater victory given to Islam before Ḥudaybiyyah that was bigger than Ḥudaybiyyah. Not a single intelligent person heard about Islam except that he accepted it. Within two years of Ḥudaybiyyah, the number of Muslims doubled, or more.”[38] Ibn Hishām comments on al-Zuhrī’s statement, adding, “There were 1,400 people in the Pledge of Divine Acceptance (Bay’atul-Ridwan), and two years later in the Conquest of Mecca, there were 10,000 people.”[39]

These letters made the presence of the Prophet ﷺ felt far beyond Medina, and brought the attention of the Roman and Persian empires. As mentioned earlier Kisra was enraged by the Prophet’s ﷺ letter and ordered his arrest. This incident led to the Persian governor in Yemen Bādhān ibn Sāsān accepting Islam and Yemen becoming the first real province (wiliyah) of the state with Bādhān its first governor (wali). Prior to this the tribal heads would simply manage their local affairs as mini-provinces. Even within Medina the sub-clans of the Aws and Khazraj had acted as mini-provinces since the beginning of the Hijra.

The same occurred in Bahrain, which also became a governorate for the Islamic State when its ruler Al-Mundhir ibn Sawa embraced Islam after receiving a letter from the Prophet ﷺ.[40]

If we look at the size of the Islamic State’s army we can see this massive increase in numbers. On entering Medina after the Hijra the Prophet ﷺ undertook a census of available fighters which was 1500 men.[41] If we fast forward to the Battle of Tabuk then we see that the army had increased to 30,000 soldiers!

The Islamic State is not a utopia, as we can see from all the difficulties faced by the Prophet ﷺ and sahaba when establishing and solidifying the state in Medina. Problems are simply part of life, which is why a government is needed in the first place. Imam Ghazali says, “a sultan is necessary for achieving well-ordered worldly affairs, and well-ordered worldly affairs are necessary for achieving well-ordered religious affairs, and well-ordered religious affairs are necessary for achieving happiness in the hereafter, which is decidedly the purpose of all the prophets.”[42]

The creation of the Islamic State in Medina and the Islamic civilisation encompassed many lands and diverse peoples, transforming the lives of those it ruled over by establishing true justice. Even many non-Muslims have attested to this fact. Carly Fiorina, the former CEO of Hewlett Packard said in a speech in 2003, “It [Islamic world] was a civilization that was able to create a continental super-state that stretched from ocean to ocean, and from northern climes to tropics and deserts. Within its dominion lived hundreds of millions of people, of different creeds and ethnic origins. One of its languages became the universal language of the world, the bridge between the peoples of a hundred lands.”[43]

Notes

[1] The Byzantine-Sasanian War (602-628CE). The Persian conquest of Jerusalem in 614 CE was celebrated by the Quraysh in Mecca as a victory for paganism. Allah (Most High) then revealed Surah Al-Rum prophesising the defeat of the Persians in 3-9 years. Allah (Most High) says, “Alif-Lam-Mim. The Romans have been defeated in a nearby land. Yet following their defeat, they will triumph within three to nine years.”

The Roman Emperor Heraclius offered peace to the Persian Emperor Khosrow in 624, threatening otherwise to invade Iran, but Khosrow rejected the offer. On March 25, 624, Heraclius left Constantinople to attack the Persian heartland. He won a decisive victory paving the way for the final recapturing of Jerusalem in 628 which occurred at the same time as the signing of the Treaty of Hudaibiyah and the despatching of letters by the Prophet ﷺ to the Roman and Persian emperors.

Dr. Mustafa Khattab says, “This Meccan sûrah takes its name from the reference to the Romans in verse 2. The world’s superpowers in the early 7th century were the Roman Byzantine and Persian Empires. When they went to war in 614 CE, the Romans suffered a devastating defeat. The Meccan pagans rejoiced at the defeat of the Roman Christians at the hands of the Persian pagans. Soon verses 30:1-5 were revealed, stating that the Romans would be victorious in three to nine years. Eight years later, the Romans won a decisive battle against the Persians, reportedly on the same day the Muslims vanquished the Meccan army at the Battle of Badr [13 March 624].” [Dr. Mustafa Khattab, ‘The Clear Qur’an: A Thematic English Translation’]

Most commentators of the Qur’an when explaining this verse mention that the Muslims were hoping for the Romans to be victorious over the Persians, because the Romans were people of the Book whereas the Persians were mushrikeen like Quraish.

Ibn Attiyah however, has an alternative explanation of this verse. In his Tafseer, Muharar al-Wajiz (المحرر الوجيز) he asserts that the main reason why the Muslims rejoiced on hearing of the Roman’s victory was not because the Romans were people of the book, or that their victory would prove the truthfulness of the Qur’an. It was rather from a strategic viewpoint that a victory for the Romans would be in the best interests of the Muslims. Ibn Attiyah writes, “what is closer to the truth in the matter is that Muslims wanted the weaker enemy to win, for if the greater and stronger enemy won, they would become a more formidable foe (for the Muslims in the future). Reflect on this point while you keep in mind that the Messenger of Allah ﷺ wanted his religion to reign supreme over all other nations.”

[2] Fred M. Donner, ‘The Expansion of the Early Islamic State,’ 2008, Routledge, p.39; John J Saunders, ‘The Nomad as Empire Builder: A Comparison Of The Arab And Mongol Conquests’

[3] Fred Donner, ‘The Early Islamic Conquests,’ Princeton University Press, 1981, p.69

[4] Rached Ghannouchi, ‘Public Freedoms in the Islamic State,’ World Thought in Translation, Translated by David L. Johnston, Yale Books, 2022, p.123

[5] Fred Donner, ‘The Early Islamic Conquests,’ Princeton University Press, 1981, p.60

[6] Dr Ali Muhammad As-Sallaabee, ‘The Noble Life of the Prophet ﷺ,’ p.173

[7] Dr Ali Muhammad As-Sallaabee, ‘The Noble Life of the Prophet ﷺ,’ p.1625

[8] https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/state

[9] Muhammad Hussein Abdullah, ‘Al-Waadih Fee Usool ul-Fiqh,’ 1995, First Translated English Edition 2016, p.555

[10] Edward William Lane, ‘An Arabic-English Lexicon,’ Part 3, p.935. https://ejtaal.net/aa/#hw4=361,ll=978,ls=5,la=1455,sg=398,ha=234,pr=58,vi=151,mgf=313,mr=236,mn=433,aan=195,kz=761,uqq=108,ulq=734,uqa=137,uqw=559,umr=377,ums=310,umj=260,bdw=331,amr=231,asb=302,auh=583,dhq=185,mht=304,msb=84,tla=49,amj=251,ens=1,mis=671,br=343

[11] Fred Donner, ‘The Articulation of Early Islamic State Structures,’ Routledge, 2012, p. xiii

[12] B. Lewis, Ch. Pellat and J. Schacht, ‘The Encyclopaedia of Islam,’ Volume II, Leiden E.J. Brill, 1991, p.178

[13] Elizabeth Suzanne Kassab. Contemporary Arab Thought: Cultural Critique in Comparative Perspective. Columbia University Press, 2010. p.40

[14] Ali Abdel Razek, ‘Islam and the Foundations of Political Power,’ a translation of Al-Islam Wa Usul Al-Hukm, 1925, Translated by Maryam Loutfi, Aga Khan University-ISMC; Edinburgh University Press, 2013, p.64

[15] Kamal Abu-Zahra, ‘The Centrality of Khilafah in Islam,’ p.30

[16] Kamal Abu-Zahra, ‘The Centrality of Khilafah in Islam,’ p.45

[17] Rached Ghannouchi, ‘Public Freedoms in the Islamic State,’ World Thought in Translation, Translated by David L. Johnston, Yale Books, 2022, p.122

[18] Rached Ghannouchi, ‘Public Freedoms in the Islamic State,’ World Thought in Translation, Translated by David L. Johnston, Yale Books, 2022, p.117

[19] Fred Donner, ‘The Articulation of Early Islamic State Structures,’ Routledge, 2012, p.2

[20] empire simply means, “a group of countries or regions that are controlled by one ruler or one government.” https://www.britannica.com/dictionary/empire#:~:text=1,by%20an%20emperor%20or%20empress

In no way is an Islamic empire comparable to the colonial empires of the Europeans.

Hugh Kennedy says, “The use of the word “empire” to describe the early Muslim state is of course controversial, and it has no equivalent in the Arabic sources. The Arabic word dawla, often used to describe the Abbasid regime has none of the hegemonic over-tones of “empire”. The “empire” I refer to is the first caliphate, which lasted from the time of the election of Abu Bakr after the death of the Prophet in 11/632 to the collapse of the last remaining vestiges of the power of the ‘Abbasid caliphs of Baghdad in 323/935. The empire began as essentially an Arab-dominated polity, but by the time of its collapse the elite was multi-ethnic and defined by its Muslim faith and its allegiance to the Abbasid cause. The use of the term “empire” will seem in-appropriate to some, but I use it to describe a political system in which a dominant elite rules over a collection of countries in which different areas have their own ethnic and cultural identities. Among the defining features of such a polity is the role of a dominant ideology, in this case Islam and the loyalty to a ruling dynasty. It also has an elite that is pan-imperial, that is to say that it can exercise power in many different areas of the empire and its loyalties are to the centre and to other members of the elite, rather than to the local communities over which it exercises power. These criteria are, of course, more a working definition than a defining statement of political theory, but I hope they will help to clarify the issues with which I am dealing. I use the term without any negative or pejorative (“evil empire”) connotations, but simply as a description of a certain type of polity.” https://www.degruyterbrill.com/document/doi/10.1515/islm.2004.81.1.3/html

[21] Sahih al-Bukhari 438, https://sunnah.com/bukhari:438

[22] Fred Donner, ‘The Articulation of Early Islamic State Structures,’ Routledge, 2012, p.2

[23] Fred Donner, ‘The Early Islamic Conquests,’ Princeton University Press, 1981, p.54

[24] “Umar came to the Prophet ﷺ when he was in his (مَشْرُبَةٍ).” Sunan Abi Dawud 5201, https://sunnah.com/abudawud:5201

[25] Dr Ali Muhammad as-Sallabi, ‘Umar ibn Al-Khattab his life and times,’ vol.2, p.306

[26] Sayed Khatab, ‘The Power of Sovereignty-The Political and Ideological Philosophy of Sayyid Qutb,’ Routledge, 2006, p.35

[27] Holy Qur’an, Surah Al-Najm, ayaat 3-4

[28] Musnad Ahmad 1342, https://sunnah.com/ahmad:1342

[28.5] Sahih al-Bukhari 4341, 4342, https://sunnah.com/bukhari:4341

[29] Holy Qur’an, Surah Al-Nur, ayah 55

[30] Alī ibn Ahmad al-Wāhidī, Asbāb al-Nuzūl, translated by Mokrane Guezzou, 2008 Royal Aal al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought, p.120

[31] Holy Qur’an, Surah Al-Fath, ayah 1

[32] Dr Yasir Qadhi, ‘The Sirah of the Prophet ﷺ,’ The Islamic Foundation, 2023, p.401

[33] Ibid

[34] Sayyid Qutb, Fee Dhilaal Al-Qur’an (1/29)

[35] Munir Muhammad al-Ghadban, al-Manhaj al-haraki lil-sirah al-nabawiyah, (1/67, 68)

[36] Dr Ali Muhammad As-Sallaabee, ‘The Noble Life of the Prophet ﷺ,’ p.1527

[37] Ibid, p.1527

[38] Ibn Hishām, al-Sīrah al-Nabawiyyah, vol. 3, pp. 268-269

[39] Ibn Hishām, al-Sīrah al-Nabawiyyah, vol. 3, p.269

[40] Dr Ali Muhammad As-Sallaabee, ‘The Noble Life of the Prophet ﷺ,’ p.1620

[41] Dr Ali Muhammad As-Sallaabee, ‘The Noble Life of the Prophet ﷺ,’ p.882

[42] Al-Ghazali’s Moderation in Belief: Al-Iqtiṣād fi al-I‘tiqād, translated by A M Yaqub, University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 2013, p.229

[43] https://www.hp.com/hpinfo/execteam/speeches/fiorina/aef2003.html#:~:text=While%20modern%20Western%20civilization%20shares,Cairo%2C%20and%20enlightened%20rulers%20like