- The Nomadic Zone

- Quraysh

- The Empires

- Alliances with Arab Tribes

- Alliances with the Arab Kingdoms

- The letter to the Persian Emperor

- The letter to the Roman Emperor

- The Islamic State of Prophet Muhammad ﷺ

- Notes

The Nomadic Zone

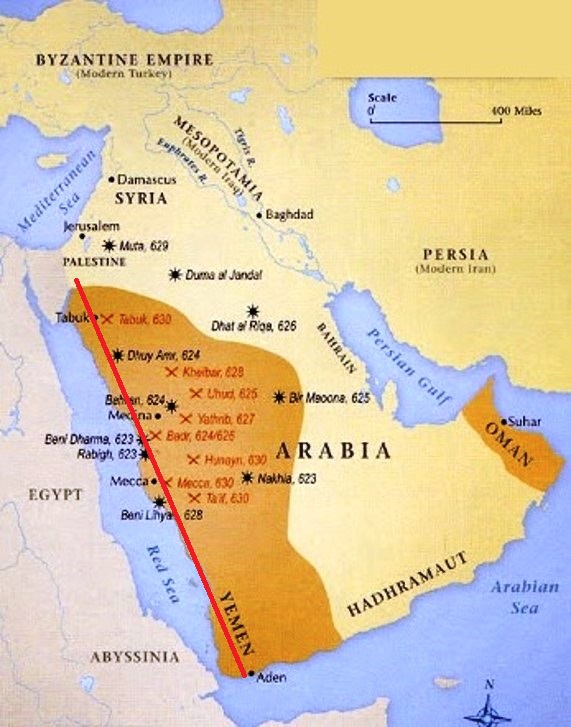

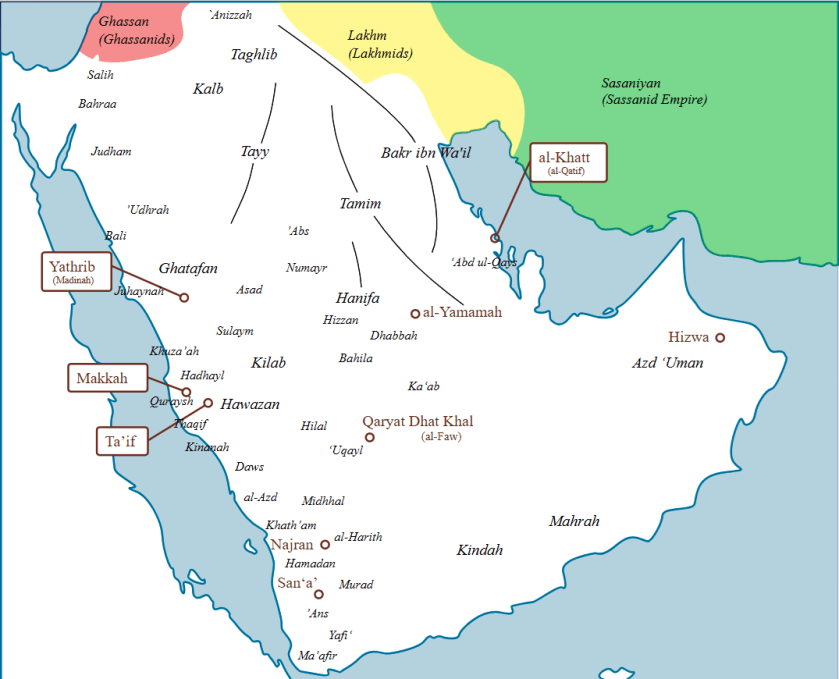

Islam emerged in the town of Mecca which was part of the Nomadic Zone in Hejaz, a strip of land in western Arabia running parallel to the Red Sea. A series of tribes lived in this Nomadic Zone, some were settled in towns such as Mecca, Taif and Yathrib, and others lived as Bedouins out in the desert.

Fred Donner describes the environment in the Nomadic Zone, “There was, then, no state in northern Arabia to impose its control over the tribes, so that society was dominated by the most powerful tribal groups-which were, as we have seen, those focused around warrior nomads or holy families. Despite the fact that confederations headed by warrior nomads as well as those headed by holy families lacked the administrative and legal features that we associate with the state, however, they did resemble the state in one respect: they functioned as sovereign entities, independent of external political control and desiring to extend their domination over new groups and areas. This meant not only that they acted as rivals to one another, as we have seen, but also that in those regions where confederations came into contact with established states on the peripheries of northern and central Arabia, the two tended to clash.”[1]

In the Nomadic Zone, the constant warring between tribes, idol worship and the shocking social practice of burying daughters alive, is why this period prior to the coming of Islam is known as jahiliyyah (time of ignorance). “Early Islamic historians have coined the term (Jahiliyyah) to describe the chaos that prevailed in the zone of nomadic power during 5th and 6th centuries, before the advent of Islam. The term Jahiliyyah might be painting to the spiritual ignorance of that era but it also definitely pinpoints the political and social chaos that existed. There is a unanimous agreement among historians that during the fifty years or so before the advent of Islam nomadic zone of Arabia was a devastated and ruined land”[2]

Quraysh

Quraysh was the dominant tribe in Hejaz and in fact all of Arabia due to its control of the haram (noble sanctuary) housing the Ka’ba, where pilgrims from the Arab tribes would flock each year to perform the annual Hajj. It also dominated Hejaz due to its monopoly on the trade route between Yemen and Ash-Sham.

There were no kingdoms or states as we know them in the Nomadic Zone. Quraysh contained a number of sub-tribes or clans who jointly ran the political and economic affairs of Mecca. Yasir Qadhi says, “The people of Mecca did not have one ruler. Instead, they deferred to a council of senior figures. Their rule can be described as a form of aristocracy. Each tribe had a leader, and each leader held a seat on this senior council.”[3] This council was called Dār al-Nadwah (دار النَدوَة). It’s the same council where the Quraysh gathered to plot the assassination of the Prophet ﷺ in order to prevent him from migrating to Medina and establishing an authority there.

The other major city in Hejaz was Ṭā’if, 100km north of Mecca, which was inhabited by the Thaqif tribe. The Qur’an references this city, وَقَالُوا۟ لَوْلَا نُزِّلَ هَـٰذَا ٱلْقُرْءَانُ عَلَىٰ رَجُلٍۢ مِّنَ ٱلْقَرْيَتَيْنِ عَظِيمٍ “And they exclaimed, “If only this Quran was revealed to a great man from ˹one of˺ the two cities!”[4]

Similar to the situation in Mecca, they did not have one ruler but were ruled by three brothers – Abd Yālīl, Masʿūd, and Ḥabīb. It is these three that the Prophet ﷺ spoke to on his famous trip to Ta’if after the death of his uncle Abu Talib, and loss of protection in Mecca effectively rendering him “stateless”.

After the conquest of Mecca, we see singular leadership in the Hejaz where “before becoming Muslim, people used to call the Prophet ‘Amir of Mecca’ and ‘Amir of the Ḥijâz’.”[5] This shows a clear distinction between the old and new governing structures in the Hejaz.

The noblest of the Quraysh sub-tribes was Banu Hashim, named after the Prophet Muhammad’s ﷺ great-grandfather. Yasir Qadhi says, “Hāshim’s name was ʿAmr, but he would grind (hashama) barley for the Hajj pilgrims and thus became known as Hāshim (The Grinder) due to his generosity. After a deadly drought, he was responsible for the economic success of the Quraysh after founding the idea of the bi-yearly trade routes to Rome in the summer, and Yemen in the winter. The Qur’an references this in Sūrah Quraysh, ‘For [the favour of] making the Quraysh secure—secure in their trading caravan [to Yemen] in the winter and [Syria] in the summer—let them worship the Lord of this Sacred House, Who fed them against hunger and made them secure against fear.’”[6]

The Prophet ﷺ said: “Verily Allah granted eminence to Kinānah from amongst the descendants of Ismāʿīl, and he granted eminence to the Quraish amongst Kinānah, and he granted eminence to Banū Hāshim amongst the Quraish, and he granted me eminence from the tribe of Banu Hashim.”[7] The Prophet’s lineage is therefore the most noble lineage to exist.

This camel route established by Hāshim brought caravans of goods from the Indian Ocean via the port of Aden to the Byzantines in Ash-Sham[8]. Montgomery Watt, mentions that the Quraysh “were prosperous merchants who had obtained something like a monopoly of the trade between the Indian Ocean and East Africa on the one hand and the Mediterranean on the other.”[9]

Securing these caravans was of utmost importance to Quraysh, so they established a network of tribal alliances along the camel route, which not only provided security from highway robbers, but also rest stops for the camels and merchants. This was seen as a far safer route than the potentially hazardous conditions a merchant ship could fall into on the Red Sea. George Hourani describes this preferred route, “Rather than face the terrors of the Red Sea, the Arabs developed camel routes along the whole western side of their peninsula.”[10]

This made Quraysh the dominant force in Hejaz. It also explains why the elites of Quraysh were so desperate to stop the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ from establishing a state. This new state in Yathrib (later renamed to Medina), a city 450km north of Mecca, would threaten their summer trade caravans to Ash-Sham which provided an economic lifeline to Mecca or more accurately the rich and powerful of Mecca at the expense of the lower classes, which is a common theme throughout history and up to today. This is why in a final act of desperation they conspired to assassinate the Prophet ﷺ to prevent his migration to Medina.

The Empires

Arabia was flanked by two great empires – the Byzantines (Romans) in the West and the Sassanids (Persians) in the East. These empires did not venture into the Nomadic zone directly, but rather relied on proxies and local alliances with Arab tribes to police and maintain control of the nomadic Arabs. The Romans and the Persians never anticipated in their wildest dreams, that out of the Nomadic Zone of Arabia would emerge an empire and civilisation which after its establishment, would destroy their own empires within 30 years.

Fred Donner describes the situation of how the empires-controlled Arabia. “Because they could not control central and northern Arabia directly, the South Arabian, Byzantine, and Sasanian states relied primarily on policies of alliance to keep the nomads of that region from interfering too seriously in their domains. These alliances assumed one of two forms, corresponding to the two kinds of tribal confederation that existed in northern and central Arabia: alliances directly with tribal confederations dominated by warrior nomads, who then served the state as “policemen”; and alliances with settled dynasties of nobles, which dominated confederations of tribes in the same manner as the religious aristocracy.”[11]

Alliances with Arab Tribes

In the 10th year of Prophethood, Allah (Most High) ordered the Prophet ﷺ to expand the seeking of authority to Arab tribes outside of Mecca, since no further progress could be made with Quraysh in achieving the establishment of a new state to protect, implement and propagate Islam to the world. Ali ibn Abi Talib said, “When Allah ordered His Messenger to present himself to the tribes of the Arabs, he left, along with myself and Abu Bakr, for Mina.”[12]

The Persian Empire had an alliance with Bakr ibn Wa’il who spanned North Eastern Arabia and Iraq. One of Bakr ibn Wa’il’s sub-tribes was Banu Shayban bin Tha’laba. This is one of the tribes that the Prophet ﷺ met and discussed with at Mina with the aim of providing protection to the message and the eventual establishment of a political authority.

At Mina during the annual Hajj season the Prophet ﷺ met with Banu Shayban bin Tha’laba. He spoke with their sheikh and military leader Al-Muthanna bin Haritha who said, “I heard and liked what you said, Oh Quraysh brother. I was impressed by your words. But our answer should be that of Hani’ bin Quhaysa[13]; for us to leave our religion and follow you after one sitting with us would be like us taking residence between two pools of stagnant water, one al-Yamama and the other al-Samawa[14].” The Messenger of Allah ﷺ asked “And what might those pools of stagnant water be then?”

Al-Muthanna replied, “One of these is where land extends to the Arab world, and the other is that of Persia and the rivers of Kisra (Persian Emporer). We would be reneging on a pact that Kisra has placed upon us to the effect that we would not cause an incident and not give sanctuary to a troublemaker. This policy you suggest for us is such a one that kings would dislike.

As for those areas bordering Arab lands, the blame of those so acting would be forgiven and excuses for them be accepted, but for those areas next to Persia, those so acting would not be forgiven, and no such excuses would be accepted. If you want us to help and protect you from whatever relates to Arab territories alone, we should do so.”

The Messenger of Allah ﷺ replied, “Your reply is in no way had, for you have spoken eloquently and truthfully. (But) Allah’s religion can only he engaged in by those who encompass it from all sides.”

He ﷺ then asked, “Supposing it were only shortly after now that Allah were to award you their lands and properties and furnished you their young women, would you then praise Allah and revere Him?”[15]

Banu Shayban later accepted Islam and al-Muthanna bin Haritha was appointed by Abu Bakr as the Amir ul-Jihad for the Iraq campaign against the Persians, their former allies.[16]

The Prophet’s ﷺ statement, “Allah’s religion can only he engaged in by those who encompass it from all sides,” shows the state he was establishing was completely different to what had existed previously in Arabia. This state would not be confined to a specific geographical area but would expand to encompass the Roman and Persian Empires.

Alliances with the Arab Kingdoms

There were two main Arab vassal states bordering the Nomadic Zone. These provided a buffer zone for the empires against any attempts by the nomadic Arabs to infiltrate their lands. This is why the first encounters with the Romans and Persians by the Islamic State were through these kingdoms.

The Lahkmid Kingdom in North-East Arabia and Iraq was a vassal for the Persians.

The Ghassanid Kingdom in Ash-Sham was a vassal for the Byzantines. It was against the Ghassanids that the Battle of Mut’ah took place and later the Battle of Tabuk.

The Persian emperor also established direct rule through governorates in Yemen and Bahrain.

In Yemen, the Persians established direct rule after they defeated the Abyssinian Kingdom of Aksum in 570CE. This year corresponds to the Year of the Elephant, when the Abyssinian general Abraha attempted to destroy the Ka’ba. His plan failed, and Abraha and his army were destroyed by a flock of birds who bombarded them with clay stones shredding them to pieces.

Allah (Most High) says, “Do you not see what your Lord did with the Companions of the Elephant? Did He not bring all their schemes to nothing, unleashing upon them flock after flock of birds, bombarding them with stones of hard-baked clay, making them like stripped wheatstalks eaten bare?”

The Year of the Elephant is also the year the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ was born.

Immediately after the signing of the Treaty of Hudaibiyah in 6Hijri (628CE), the Prophet ﷺ despatched letters to the leaders of all the major powers in the region. These included not just the vassal states of the Lahkmids and Ghassanids, but also directly to the Byzantine and Sassanid emperors.

The letter to the Persian Emperor

Chosroes II (r. 590 to 628CE) known as Kisra in Arabic, was the Sassanid emperor (shāhanshāh). The Prophet ﷺ sent Abdullah ibn Hudhafah As-Sahmi to Bahrain with Kisra’s letter. There he handed it over to Bahrain’s Persian Governor Al-Mundhir Ibn Saawa who then passed it on to Kisra.

Kisra was enraged when he received the Prophet’s ﷺ letter. After the letter was read out Kisra took it, tore it apart, and said, “He writes to me when he is my slave!” Upon learning of Kisra’ s response, the Messenger of Allah ﷺ said, “May Allah tear apart his kingdom!”[17]

Kisra then ordered is governor in Yemen Bādhān ibn Sāsān to arrest the Prophet ﷺ and bring him to his court. Bādhān sent a messenger to Medina with a letter: “Verily, the king of kings (shāhanshāh) has written to the king Bādhān, ordering him to send someone to you, and take you to him.” The Prophet ﷺ then shocked the messenger by informing him that Kisra had just been assassinated by his son Shairawai (Sheroe/Kavad II).[18] When Bādhān heard the news of Kisra’s demise and the fact that the Prophet ﷺ knew it had occurred, he accepted Islam. Yemen then left the Persian Empire becoming a new governorate for the Islamic State.

The same occurred in Bahrain, which also became a governorate for the Islamic State when its ruler Al-Mundhir ibn Sawa embraced Islam after receiving a letter from the Prophet ﷺ .[19]

The letter to the Roman Emperor

Heraclius (r. 610-641CE) known as Heraql in Arabic was the Byzantine emperor. The Prophet ﷺ sent Dihyah al-Kalbi with a letter to Heraclius inviting him to Islam. After receiving the letter Heraclius ordered his men to find someone from Quraysh who he could question about this new prophet. As discussed, Quraysh had economic ties to Ash-Sham through their trade route from Yemen.

Abu Sufyan who at the time was not Muslim, happened to be in Ash-Sham on business. He narrates that Heraclius sent for him to come along with a group of the Quraish who were trading in Sham, and so they came to him. Abu Sufyan then mentioned the whole narration and said, “Heraclius asked for the letter of Allah’s Messenger ﷺ. When the letter was read, its contents were as follows: ‘In the name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful. From Muhammad, Allah’s slave and His Messenger to Heraclius, the Chief of Byzantines: Peace be upon him who follows the right path (guidance)! Amma ba’du (to proceed)…’”[20]

Abu Sufyan’s son Mu’awiya became the governor of Ash-Sham under Umar ibn al-Khattab, and later the caliph of the Muslims.

These close links between Quraysh and the Byzantine empire, and between Quraysh and the Persian Arab allies via the Hajj, show that the Prophet ﷺ and the sahaba (companions) were fully aware of the ruling structures in the empires and their vassal kingdoms. In spite of this the Prophet ﷺ established a unique state and did not copy these existing governing structures in terms of their ruling principles. In administrative aspects such as military tactics he did copy the Persians (Battle of the Trench) because administration is one of the principles of ruling as will be discussed later.

When the Messenger of Allah ﷺ was informed that the Persians had crowned the daughter of Chosroes as their ruler, he ﷺ said, “People who appoint a woman over their affairs will never succeed.”[21] Meaning it is not permitted for the caliph to be a woman.

Near the end of Mu’awiya ibn Abi Sufyan’s reign as caliph (661-680CE) he embarked on a course of action of introducing hereditary rule, which was not from the Islamic ruling principles, but rather from the Roman and Persian civilisations. There was major opposition from the senior sahaba to his attempts to make his son Yazid the caliph after him.

Mu’awiya wrote to his governor in Medina Marwan ibn Al-Hakam to take the bay’a for Yazid. Marwan addressed the people: “The Ameer of the Believers has decided to appoint his son, Yazid, as his successor over you, according to the sunna of Abu Bakr and ʿUmar.” Abd al-Rahman ibn Abi Bakr (d.675CE) stood up and said, “Rather, according to the sunna of Chosroes and Caesar! Abu Bakr and ʿUmar did not appoint their sons to it, nor anyone from their families.”[22]

The Islamic State of Prophet Muhammad ﷺ

The emergence of the first Islamic State in 622CE went unnoticed at first by the Sassanid and Byzantine empires. The Persians and Romans were fighting each other in a major war[23], and so their focus was not on the nomadic Arabs who had never previously posed any type of threat to their empires.

John Saunders says, “Once and once only, did the tide of nomadism flow vigorously out of Arabia. Bedouin raids on the towns and villages of Syria and Iraq had been going on since the dawn of history, and, occasionally an Arab tribe would set up a semi-civilized kingdom on the edge of the desert, as the Nabataeans did at Petra or the Palmyrenes at Tadmur, but conquests only occurred at the rise of Islam.”[24]

It is from this environment that a new state emerged in Medina, which was something out of the ordinary in Nomadic Arabia which had never known a state like this before.

Notes

[1] Fred Donner, ‘The Early Islamic Conquests,’ Princeton University Press, 1981, p.41

[2] https://historyofislam.org/pre-islamic-arab-politics/

[3] Dr Yasir Qadhi, ‘The Sirah of the Prophet ﷺ,’ The Islamic Foundation, 2023, Chapter ‘Opposition from the Quraysh’

[4] Holy Qur’an, Surah Al-Zukhruf, ayah 31

[5] Ibn Khaldun, ‘The Muqaddimah – An Introduction to History,’ Translated by Franz Rosenthal, Princeton Classics, p.287

[6] Dr Yasir Qadhi, ‘The Sirah of the Prophet ﷺ,’ The Islamic Foundation, 2023, p.49

[7] Sahih Muslim 2276, https://sunnah.com/muslim:2276

[8] Syria, Palestine, Jordan, Lebanon

[9] Watt, W. Montgomery (1986). “Kuraysh”. The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume V: Khe–Mahi. Leiden and New York: BRILL. p.434

[10] George Hourani, ‘Arab Seafaring in the Indian Ocean in Ancient and Early Medieval Times,’ Octagon Books, New York 1975, p.5

[11] Fred Donner, ‘The Early Islamic Conquests,’ Princeton University Press, 1981, p.42

[12] Ibn Kathir, ‘Al-Sira al-Nabawiyya,’ Vol.2, Garnet Publishing, p.109

[13] Another leader of the tribe

[14] Al-Samawa is in Southern Iraq

[15] Ibn Kathir, ‘Al-Sira al-Nabawiyya,’ Vol.2, Garnet Publishing, p.111

[16] Dr Ali Muhammad As-Sallaabee, ‘The Biography of Abu Bakr As-Siddeeq’, Dar us-Salam Publishers, p.557

[17] Dr Ali Muhammad As-Sallaabee, ‘The Noble Life of the Prophet ﷺ,’ p.1623

[18] Ibid, p.1623

[19] Ibid, p.1620

[20] Sahih Bukhari 6260, https://sunnah.com/bukhari:6260

[21] Sahih al-Bukhari 4425, https://sunnah.com/bukhari/64/447

[22] Jalal ad-Din as-Suyuti, ‘History of the Umayyad Khaleefahs,’ translated by T.S.Andersson, Ta Ha Publishers, p.24

[23] The Byzantine-Sasanian War (602-628CE). The Persian conquest of Jerusalem in 614 CE was celebrated by the Quraysh in Mecca as a victory for paganism. Allah (Most High) then revealed Surah Al-Rum prophesising the defeat of the Persians in 3-9 years. Allah (Most High) says, “Alif-Lam-Mim. The Romans have been defeated in a nearby land. Yet following their defeat, they will triumph within three to nine years.”

The Roman Emperor Heraclius offered peace to the Persian Emperor Khosrow in 624, threatening otherwise to invade Iran, but Khosrow rejected the offer. On March 25, 624, Heraclius left Constantinople to attack the Persian heartland. He won a decisive victory paving the way for the final recapturing of Jerusalem in 628 which occurred at the same time as the signing of the Treaty of Hudaibiyah and the despatching of letters by the Prophet ﷺ to the Roman and Persian emperors.

Dr. Mustafa Khattab says, “This Meccan sûrah takes its name from the reference to the Romans in verse 2. The world’s superpowers in the early 7th century were the Roman Byzantine and Persian Empires. When they went to war in 614 CE, the Romans suffered a devastating defeat. The Meccan pagans rejoiced at the defeat of the Roman Christians at the hands of the Persian pagans. Soon verses 30:1-5 were revealed, stating that the Romans would be victorious in three to nine years. Eight years later, the Romans won a decisive battle against the Persians, reportedly on the same day the Muslims vanquished the Meccan army at the Battle of Badr [13 March 624].” [Dr. Mustafa Khattab, ‘The Clear Qur’an: A Thematic English Translation’]

Most commentators of the Qur’an when explaining this verse mention that the Muslims were hoping for the Romans to be victorious over the Persians, because the Romans were people of the Book whereas the Persians were mushrikeen like Quraish.

Ibn Attiyah however, has an alternative explanation of this verse. In his Tafseer, Muharar al-Wajiz (المحرر الوجيز) he asserts that the main reason why the Muslims rejoiced on hearing of the Roman’s victory was not because the Romans were people of the book, or that their victory would prove the truthfulness of the Qur’an. It was rather from a strategic viewpoint that a victory for the Romans would be in the best interests of the Muslims. Ibn Attiyah writes, “what is closer to the truth in the matter is that Muslims wanted the weaker enemy to win, for if the greater and stronger enemy won, they would become a more formidable foe (for the Muslims in the future). Reflect on this point while you keep in mind that the Messenger of Allah ﷺ wanted his religion to reign supreme over all other nations.”

[24] Fred M. Donner, ‘The Expansion of the Early Islamic State,’ 2008, Routledge, p.39; John J Saunders, ‘The Nomad as Empire Builder: A Comparison Of The Arab And Mongol Conquests’