This is an excerpt from the book ‘Fatwa and the Making and Renewal of Islamic Law: From the Classical Period to the Present’ by Omer Awass.[1]

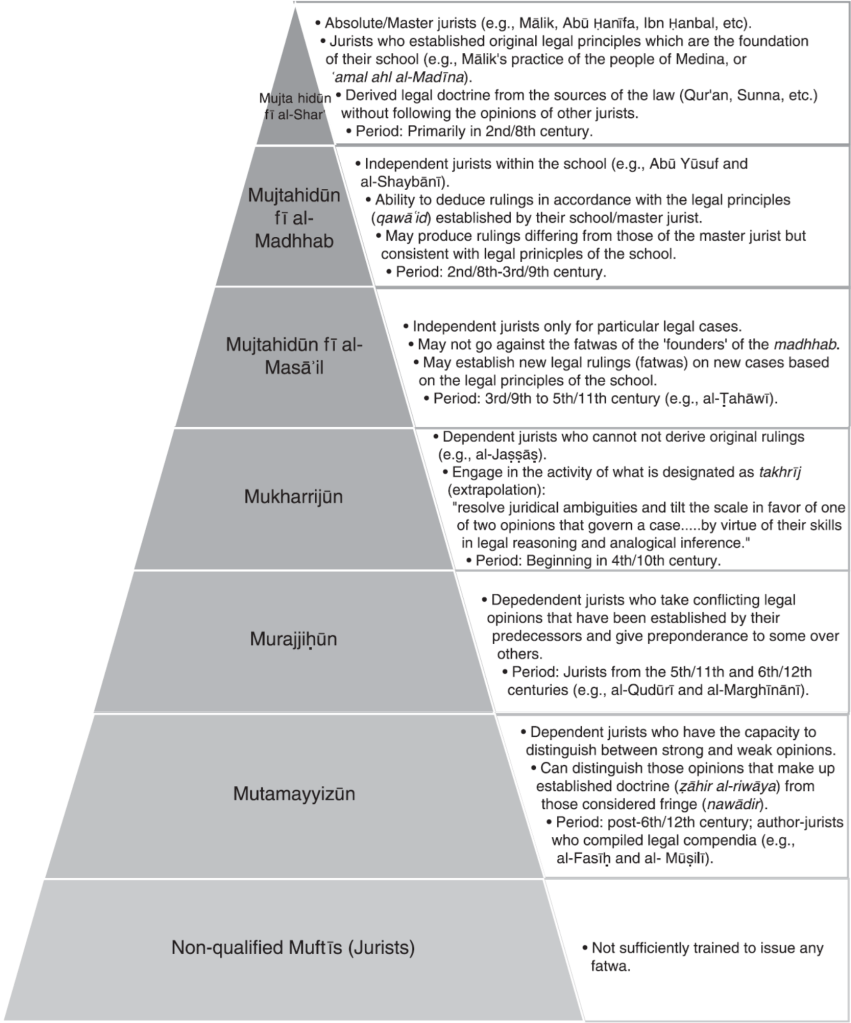

- al-mujtahidı̄n fı̄ al-sharʿ (Independent Jurists)

- mujtahidūn fı ̄ al-madhhab (Jurists within a school)

- mujtahidūn fı ̄ al-masāʾil (Jurists on specific issues)

- mukharrijūn (extrapolation of opinions)

- murajjiḥun (preponderance to one opinion over another)

- mutamayyizūn (capacity to distinguish opinions)

- Unqualified Jurists

The famous Ḥanafı̄ jurist Ibn ʿĀbidı̄n (d. 1252H/1836CE) in his treatise ʿUqūd rasm al-mufti outlines a hierarchy for mujtahideen (jurists) who occupy different authoritative levels within the Ḥanafı̄ madhhab. This structure that Ibn ʿĀbidı̄n lays out consists of seven levels (ṭabaqāt).

al-mujtahidı̄n fı̄ al-sharʿ (Independent Jurists)

The first, which stands at the very top of this classification, is the level of the absolute independent jurists of Islamic law (what he calls al-mujtahidı̄n fı̄ al-sharʿ, [also known as a mujtahid mutlaq], which consists of the madhhab predecessors of the four Sunnı̄ legal schools (Abū Ḥanı̄fa, Mālik, al-Shāfiʿı̄, and Ibn Ḥanbal). These were the second-/eighth- and third-/ninth-century jurists some of whose legal opinions were examined in previous chapters. His claim is that this class of jurists established original legal principles and extracted doctrine from the sources of the law without imitating other jurists in their legal principles or their doctrines.

mujtahidūn fı ̄ al-madhhab (Jurists within a school)

The second level of jurists/muftı̄s within the Ḥanafı̄ school consists of those who, he claims, are independent jurists but within the limits of the Ḥanafı̄ madhhab (mujtahidūn fı ̄ al-madhhab). Examples of such figures in the Ḥanafı̄ school are Abū Ḥanı̄fa’s two protégés Abū Yūsuf and Muḥammad al-Shaybānı̄. Ibn ʿĀbidı̄n claims that what makes them independent jurists within the madhhab was their ability to deduce rulings in accordance with the legal principles (qawāʿid) established by their mentor, Abū Ḥanı̄fa. Thus, even when they extract different legal rulings than he, they nevertheless confine these deductions in accordance with the legal principles that Abū Ḥanı̄fa established.

mujtahidūn fı ̄ al-masāʾil (Jurists on specific issues)

At the next (third) level are the subsequent generations of Ḥanafı̄ jurists from the third/ninth to the fifth/eleventh century (e.g., al-Ṭaḥāwı̄, al-Jarrāḥ, al-Bazdawı̄, al-Sarakhsı ̄, etc.), who are what he calls the independent jurists in particular legal cases (mujtahidūn fı ̄ al-masāʾil). These are cases where there is no established legal doctrine (la riwāyah, lit. No narration) from the madhhab predecessors or the master jurists (Abū Ḥanı̄fa and his protégés). Ibn ʿĀbidı̄n tells us that this level of muftı̄ may not go against the fatwas of the founders of the madhhab, but he may select from those opinions that seem most in keeping with the principles of the madhhab and promote those as the official position of the school. He may also establish new legal rulings (fatwas) on new cases based on the legal principles established by the founders. Ibn ʿĀbidı̄n sees these first three levels of jurists to one extent or another as mujtahids (independent legal reasoners). On the other hand, jurists at levels four through seven are no longer viewed as independent jurists (mujtahidūn), or those who can make ijtihād (deducing new rulings through independent legal reasoning). Instead, these levels of muftı̄s are in the realm of what is known as taqlı̄d, which may be defined as the opposite of ijtihād in the sense that those who make taqlı̄d do not arrive at legal rulings independently, but depend on and follow those rulings that have been established in the legal doctrine of the madhhab.

So from this level onward is what we may call the level of dependent or limited muftı̄s, as their legal activities are restricted to legal principles and rulings established by the previous three levels.

mukharrijūn (extrapolation of opinions)

Level four muftı̄s consist of those jurists whose task is to engage in the activity of what is designated as takhrı̄j (extrapolation) and are known as mukharrijūn. Their capacity to make takhrı̄j of rulings is a result of their competence in legal principles (of the madhhab), and hence they are tasked to “resolve juridical ambiguities and tilt the scale in favor of one of two opinions that govern a case … by virtue of their skills in legal reasoning and analogical inference.” An example of a Ḥanafı̄ jurist in this category is al-Rāzı̄ (al-Jaṣṣāṣ).

murajjiḥun (preponderance to one opinion over another)

The fifth level consists of those jurists who are considered murajjiḥun (those who give preponderance to one opinion over another). Examples of jurists that fit this category are those Ḥanafı̄ jurists from the fifth/eleventh and sixth/twelfth centuries like al-Qudūrı̄ and al-Marghı̄nānı̄, whose task is to take conflicting legal opinions that have been established by their predecessors and give preponderance to some over others using the established standards of the madhhab.

mutamayyizūn (capacity to distinguish opinions)

The sixth level consists of those dependent muftı̄s who have the capacity to distinguish (mutamayyizūn) strong from weak opinions, as well as those opinions that make up established doctrine (ẓāhir al-riwāya) from those that are considered fringe (nawādir). Examples of this type are those post-sixth-/twelfth-century author-jurists who compiled legal compendia of the doctrines of the Ḥanafı̄ school like al-Fası ̄ḥ (d. 680/1281) and al-Mūṣilı ̄ (d. 683/1284) – the authors of al-Kanz and al-Mukhtār, respectively – whose task in these legal compendia is to present the established legal doctrines of the school and keep out of their works those legal opinions that are considered weak.

Unqualified Jurists

Those belonging to the seventh and final level are not real jurists or muftı̄s at all; rather, they are poorly trained jurists who are incapable of issuing sound fatwas.

Notes

[1] Omer Awass, ‘Fatwa and the Making and Renewal of Islamic Law From the Classical Period to the Present,’ American Islamic College, Cambridge University Press, 2023, p.130